Photos by Jerry Martin

Longer ago than most folks can imagine, stone crafting gave humans mastery over a world filled with physically superior creatures. It’s also one of mankind’s oldest art forms, born of a need to stay alive and often linked to religious ceremony.

Stone blades were mounted on arrows, spears, atlatl darts, harpoons, daggers, tomahawks, skinning knives, axes, hoes, war clubs, drills, even fishhooks. Decorative and ritual pieces included gorgets, sacrificial cutlery, amulets, medallions, rings and various other pieces of jewelry.

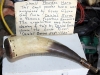

Pell City’s Roger Pate, a 30-year veteran of local artifact collecting, owns thousands of such pieces. He explains that, over the 12,000 years, countless American aboriginal tribes settled anywhere there was a reliable source of fresh water. Their very lives depended on how well they made tools and weapons.

Before mankind learned to refine metal, stone was the key element in practically every hand tool used by most primitive cultures; hence, the term Stone Age which, for isolated American Indians, lasted until they began trading with Europeans for metal goods during early colonial days.

The skill of working stone into sharp implements is called knapping. Simply put, knapping is the act of breaking and chipping away at pieces of stone to produce desirable shapes with sharp edges. It’s become a modern-day hobby among history and craft enthusiasts. Avid knappers love to compete with each other for the most beautiful and authentic pieces. New London’s Gerald Hoyle and his brother, Wayne, have become masters of the craft.

Skilled artisans like the Hoyles are notorious for having cramped, cluttered workspaces. As long as enough stuff can be pushed aside to allow room for their gifted hands and a few simple tools, a properly finished product is all that matters. And Gerald’s work is superb — remarkably so, considering he’s only been doing it for about five years.

He works seated at a waist-high bench, with the piece cushioned on a thick square of leather, and cradled in an authentic nutting stone, a rounded sandstone with a depression chiseled into its flat side. They were traditionally used by Native Americans to hold nuts for cracking.

His knapping implements consist of sharpened deer antlers, rounded “hammer stones” picked up from creek bottoms, leather for protective padding, coarse sandstone blocks for treating edges, and special flaking tools he fabricates from thick copper wire and aluminum rods mounted in regular tool handles. Gerald explains that copper has exactly the same hardness as deer antler, but smells much better when he sharpens it on a grinder.

Gerald carries on a lively conversation as he deftly chips away at a chunk of black obsidian he had just hammered off the corner of a much larger piece. It was misshapen, bulged out in all the wrong places, and looked nothing like the business end of a weapon — more like something one might skip across a pond.

But Gerald’s keen eye had visualized a shape suitable for an atlatl point within this irregular hunk of shiny stone, and proceeded apace to extract it. As he worked, the piece began to take on an isosceles triangle shape with razor sharp point, serrated sides designed to slice flesh, and elegantly crafted barbs and notches at the large end. The end result was a precision, totally lethal weapon tip for hunting or warfare.

Obsidian is an extremely fine-grained form of volcanic glass, similar to quartz and can be shaped into edges sharper than the finest steel. In fact, obsidian is made into modern instruments for delicate eye surgery, with cutting edges approaching a single molecule in width. Its sharpness and crystalline nature were further evidenced by Gerald’s fingers, which began to bleed from several tiny cuts as he worked. Knapping is definitely a labor of love, reinforced with a tetanus shot and Band-Aids.

Obsidian is an extremely fine-grained form of volcanic glass, similar to quartz and can be shaped into edges sharper than the finest steel. In fact, obsidian is made into modern instruments for delicate eye surgery, with cutting edges approaching a single molecule in width. Its sharpness and crystalline nature were further evidenced by Gerald’s fingers, which began to bleed from several tiny cuts as he worked. Knapping is definitely a labor of love, reinforced with a tetanus shot and Band-Aids.

Other stones are almost as sharp as obsidian when properly tooled. Flint is actually a hard, fine-grained version of chert and was used extensively by local Indians who had no nearby source of obsidian other than trading with distant tribes. Also useful were dolomite, quartz, greenstone, jasper, quartzite, stromatolite, chalcedony, even a type of iron ore called hematite. More exotic-sounding materials include Horse Creek chert, novaculite, sugar slate, Hillabee greenstone and rainbow obsidian.

Modern hobbyists love to experiment with other materials, such as glassy slag from blast furnaces and even old drink bottles melted in trash fires. The Hoyle brothers have made scores of these experimental points, some almost indistinguishable from quartz or smoky obsidian.

Born in Pahokee, Florida, Gerald moved with his family to New London in 1952, and he’s been in the neighborhood ever since. A 1963 Pell City High graduate, he served in the Air Force for four years, then worked as a truck mechanic for 32 years at Ryder in Oxford.

Now retired and a robust 67 years of age, Gerald stays very busy. When he’s not emulating Paleo Tool-Man, he enjoys photography, paleontology, collecting rocks and artifacts from local tribal sites, demonstrating his crafts to school children and preaching the gospel at Mt. Olive Freewill Baptist in Dunnavant.

He also does volunteer work at the new State Veterans’ Home in Pell City, where he entertains residents with lively conversation, games of dominos, and reading to the visually impaired.

Gerald’s wife, Mary Margaret, tolerates his hobby because it provides so many large, multicolored stones for her flower beds. Her avocation is machine embroidery and quilting. Though not a flint-knapper herself, she often helps her husband make fine jewelry from his artifacts. However, his handiwork has caused her some concern at times.

For instance, she was not happy when a pile of flint rocks which he was trying to heat-temper in her kitchen oven, exploded, filling the whole cavity with tiny slivers of razor-sharp stone. Nor does she share his enthusiasm when he loads their car down with heavy stones he’s spotted and picked up while they travel.

It’s nothing new. The Hoyle brothers’ passion for paleo crafts goes all the way back to their childhood, when they spent countless hours searching fields and river banks for stone products. Both men have extensive collections of museum-quality goods. Before he retired, Gerald often knapped on his lunch break while others…well, napped.

Gerald explains that using primitive methods while working with stone helps him reach out and touch the past, when much hardier men depended on such skills to stay alive and prosper. He especially enjoys giving his craftworks to people he likes, free of charge, and eagerly shares his love of history with others.

Would you like to try your hand at knapping? The Hoyle brothers advise aspiring knappers to start out with good materials and tools, seek the advice of experts on basic technique, and practice, practice, practice. Because of the extreme sharpness and minute size of stone flakes, it’s also mandatory that you wear old clothes, gloves and safety glasses, and never allow bare feet anywhere near your work area.

Gerald has jump-started several local folks in this fascinating hobby, including this writer. His advice includes a warning that your first few hours of work will most likely consist of turning larger rocks into lots of smaller ones before you actually create a presentable result.

Most novices will eventually produce an acceptable piece, but it seems there are always a few who never really “get the point” of this fascinating pastime.

• For a special story on the bow and arrow precursor, the atlatl, see the digital or print edition of the June 2013 edition of Discover The Essence of St. Clair •