Moody group makes quilts for veterans

Story by Elaine Miller

Photos by Richard Rybka

Every time Barbara Willingham makes a quilt for a military veteran, she remembers the time her son called her from Iraq at 2 a.m. She could hear explosions in the background. “Mom, I gotta go, we’ve been bombed,” he told her. Then he hung up, and she didn’t hear from him again for two fear-filled weeks.

“He came back, and I have my son, but not every mom does,” she says. “Every quilt I make I’m grateful I’m not going to the cemetery.”

Barbara is part of the Moody Crazy Quilters, a group of women that makes quilts for veterans, foster children, nursing home residents and hospice groups, to name a few. It’s their way of giving back to veterans and offering comfort to others who may be hurting physically or mentally.

“I like to make children’s quilts because kids wanna hold something, especially if they’re in the hospital,” says member Carolyn Snider. “I also enjoy making quilts for veterans. Our freedom is not free, and this is a way to give back to them.”

The group meets at Moody City Hall the first Monday of each month, except for holidays. It started in 2009 as a library function at Moody’s Doris Stanley Memorial Library, but soon outgrew its meeting space. They have about eight steady members, including one who moved to Marietta, Georgia, but still comes back for monthly meetings.

Most members also belong to a similar group called Loving Hands that meets at Bethel Baptist Church.

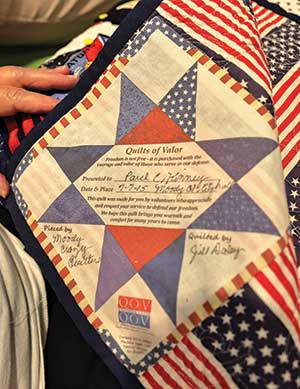

They try to identify a couple of veterans each year to quilt for, such as the two found by group coordinator Jill Dailey’s husband, an Army vet himself. The group also made a patriotic quilt for Moody Mayor Joe Lee, another Army veteran, as a thank-you for his military service and for the meeting space the city provides.

“We label our quilts, ‘Gift from Moody Crazy Quilters,’ and on our patriotic quilts we add, ‘Thank you for your service,’ ” says Jill. “We also put the year we made them on the labels.”

Once a recipient is chosen, each woman usually makes a quilt block at home, choosing her own fabric, colors and design. Then the group puts their blocks together to make one Sampler Quilt, as they are called.

“Each month people turn in their blocks, and we’ll put them in a pile and lay them out and decide what to do with them,” Jill says. “We make 12-inch blocks, using four across and five down, plus binding, and sometimes a wide sashing between rows.”

The group donates at least three patriotic quilts to veterans every year, along with several more to hospice organizations for their patients. Children’s of Alabama is another organization that benefits from the group’s quilting efforts.

“Lots of our fabric is donated by various people, but a lot comes from our own stashes,” says Carolyn, who joined the group in December 2021 after retiring.

Most are lap quilts. Those made for nursing homes have a small, fleece-lined pocket to keep hands warm. On the outside of the hand pocket is a smaller one for a phone, glasses or tissues. “Most of us don’t make standard-size quilts, but Barbara sometimes gets carried away,” Jill says.

Nearly all of these women have been quilting for years, some since they were children. “My mother taught me to quilt,” says Laura Kinney who, at 86, may be the oldest member of the group. “Ours weren’t pretty, either. They were just called ‘covers’ back then.”

She recalls the days before she retired, when she often would often get home from work at 8:30 p.m. and sew on a quilt. “I would sometimes tell my husband, ‘My hands hurt, you need to do the cookin’ tonight,’” she says. She has made a quilt for each of her children, and has a stack of 10 that measure 50 inches x 70 inches each, five blocks across by seven blocks down, ready to present to her great nieces and great nephews. She also has a quilt that she hangs on a wall at home to display her husband’s Coast Guard patches.

Some of the women own long-arm machines, others just domestic sewing machines. At least one has a Cutie Frame, a tabletop quilting frame used in conjunction with a sewing machine to do the quilting.

“Making quilts for veterans ispayback for me,” says Barbara, who volunteers at the Colonel Robert L. Howard State Veterans Home in Pell City. “Not every mother can say her son went to Iraq and came back. I know how hard it is. My son, Toussaint Edghill, is a disabled vet, and I do this to honor him.”

Gaye Austin’s husband and son are veterans, and she wants to show her appreciation to them and to all veterans “for giving us our freedom and the protection we have today,” she says.

“We want to thank the veterans for their service, and we enjoy quilting so much,” says Jill. “It’s a win-win.”