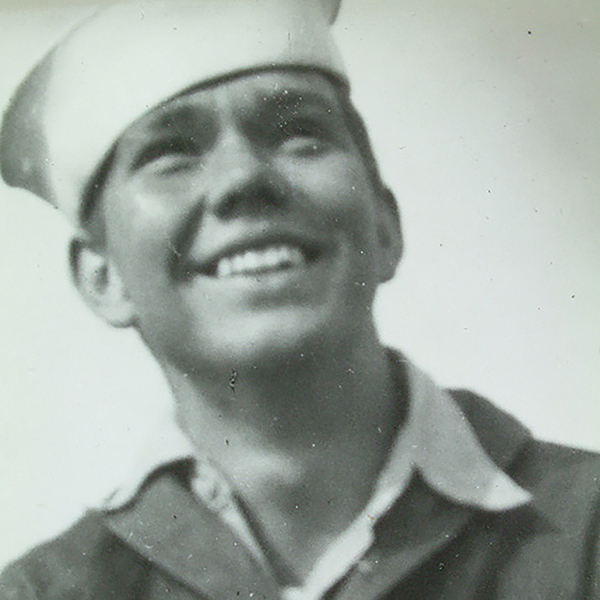

At 95, World War II vet Bob Curl recalls horror of war, an unconditional love and a wonderful life

Story by Paul South

Submitted Photos

Barely a year out of high school, Bob Curl saw things a kid his age ought never see: the shattered bodies of young men, their lives snatched in a twinkling.

He’s also known the joy that every human heart should know, the magic of an unconditional, long-lasting love that endures to this day, though its beloved is years gone.

Like a Frank Capra movie of the 1940s, Curl – now 95 – has known horror and heartbreak, love, laughter and selfless service, the stuff poured into a life well lived.

A resident of the Col. Robert L. Howard Veterans Home in St. Clair County, Curl still drives, running the roads, snapping photos of his trips with cameras from his large collection of vintage photography gear. He’s been interviewed by historians from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington and the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

His smiles and his stories are well known at the place he calls home – a wonderful place, he says, where he’s been known to join a side in a rollicking game of volleyball. “I tell people I live at a country club,” he says.

Chat with him long enough, and Curl will tell you stories of bloodied French beaches, a department store fire, the Sabbath morning he first saw the love of his life and the time he met the legendary war correspondent Ernie Pyle.

What a life.

First, let’s tackle the hard part of Bob Curl’s days.

In June 1944, his job as a Navy radarman was simple – to use the high technology of the day to find Omaha Beach. He did. In a briefing in Britain days before the invasion, the teenage sailor learned that he would be part of the first flotilla of Allied vessels, facing batteries of German 88s, heavy artillery protected by reinforced concrete pillboxes.

“We were told we were probably going to be killed,” Curl said. So, I wrote a letter to my mother. I told her I wish I’d been a better son. She didn’t know where I was or what I was doing. But I thought that was the end of me.”

A strike on one of those pillboxes, Curl believes, saved his life.

On June 9, three days after D- Day, the initial Allied thrust onto the European continent, aimed at ending Nazi occupation, Curl slogged ashore through bloodied water and shrapnel-peppered sand. What he saw is seared in memory, more than 75 years later.

“… Bodies and parts of bodies all over the place,” Curl remembered. “(Pulitzer Prize-winning newsman) Ernie Pyle came on our boat. He went on the beach the second day (June 7) and when he came back, he wrote what he saw. They censored it and wouldn’t let it go through. At that time, the only way you could make a copy was carbon paper and onion skin paper. And he submitted his story, and they thought it was too graphic and too bad. So, they censored it.”

Pyle, who was killed in the Pacific while embedded with an American unit, on D-Day wrote of bloody boots and the mundane and the strange that fighting men carried into the carnage – cigarettes and writing paper, a banjo and a tennis racket.

Pyle saw what he thought were two sticks jutting out of the sand. He was mistaken.

“They were a soldier’s two feet,” Pyle wrote. “He was completely covered by the shifting sands except for his feet. The toes of his G.I. shoes pointed toward the land he had come far to see and which we saw so briefly.”

As Pyle finished the dispatch that War Department censors quashed, Curl asked him for the trash-can-bound carbon of the story and Pyle gave it to him. It’s long lost, but after the war, as a college student struggling with an English class, Curl copied Pyle’s story word for word, hoping for a needed good grade.

“I thought, ‘Oh boy, I got him now,’” Curl said of his tough taskmaster professor.

Pyle’s work earned Curl a C+.

After victory in Europe, Curl was preparing for the invasion of Japan on Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands when he learned of victory in Japan.

A love story

He would have a personal victory once he returned home. He married his wife, the former Nell Spring. The Methodist minister’s son met his future wife at a church youth social on Valentine’s Day in 1943. They dated for three months. He enlisted in the Navy the Saturday after graduation in May.

He fell in love with her earlier that day, as he walked into church with a friend on his first Sunday in a new town.

“When I walked into church that morning, the most beautiful girl I ever saw was giving the devotion up there,” Curl recalled. “I nudged that boy next to me – I was 16 or 17 – I said, ‘I don’t know who that girl is, but I’m going to marry her.’”

It was the beginning of what would be a 69-year marriage, an old-fashioned love affair. She’s gone now, but every night, he talks with her, looking into the eyes of her picture adorning a wall in his room.

“She was the most wonderful lady I’ve ever known.”

Early years

Theirs is a magical story, one of several he tells. He got his first job in a local movie theater. Armed with a broomstick with a nail poking sharply from its end, Curl picked up trash.

His salary in the teeth of the Great Depression? “I got to see all the movies for free,” he said. The cost: One thin dime.

Another story was like something from a movie. As a nine-year-old while shopping with his mother at Birmingham’s iconic Loveman’s department store, a fire broke out, filling the store with smoke.

“We couldn’t go down the elevator,” Curl said. “I had my mother by the hand. We made it down to the first floor. The smoke was so thick, we couldn’t see. But we heard a voice telling us, ‘Come this way,’ That voice led us all the way out of the store. We got out through a broken show window.”

Ironically, Curl spent his professional life after the war as a Birmingham firefighter, who would go on to help train new recruits in the fire service. Like so many of his generation, Curl gave back to his community, while at the same time raising his family.

Now in retirement, he’s still impacting lives. A small bottle of shrapnel-laced sand from Omaha Beach – given by Curl to the veterans’ home – is part of a display honoring those who served. But more than the artifacts of war, Curl radiates happiness.

Said Hiliary Hardwick, director of the Veterans Home, “He definitely doesn’t act 95. He just has the most positive outlook on everything. I’ve never heard him or seen him when he’s upset. He just kind of takes life as it comes, and he just makes the most of it.”

She added, “He’s probably one of the most thoughtful people I’ve ever met. He generally thinks of others before himself. He’s unique. You know, they call the World War II guys ‘The Greatest Generation.’ He’s truly the epitome of that. He’s selfless in everything that he does.”

Curl, she says, “just radiates happiness.”

Curl credits his heart for others to his dad, the late Rev. John Wesley Curl, whom he calls, “the best man I ever knew.”

Asked how he would sum up his own wonderful life, Curl responds with the two words he hopes will be his epitaph:

“He tried.”