When St. Clair’s largest city was just getting started

Story by Jerry Smith

Submitted photos

What magic molded a sleepy little whistle stop of 40 souls into St. Clair County’s largest city? Actually, the town owes its success to a missed train and a fortuitous marriage. Pell City was blessed with both a father and a mother — Sumter Cogswell, who nurtured it from infancy, and Lydia DeGaris Cogswell, who helped rescue it from a premature demise.

A town charter was granted in 1887 at the request of six local businessmen: John B. Knox, T.S. Plowman, D.M. Rogers, J.A. Savery of Talladega, John Postell of Coal City and Judge John W. Inzer of Ashville. Postell was general manager of the East & West Railroad, and Inzer was the company’s attorney. The line was owned by the prominent Pell family of New York City, Pell City’s namesake. (See Discover August/September and October/November 2012 for more on that railroad.)

An official incorporation map shows that Pell City was only about eight blocks square, some 400 acres. At the time, there were few houses and even fewer buildings, the largest of them the two-story Maxwell Building, which still stands on Cogswell Avenue next to Gilreath Printing.

The East & West was a short line that connected Seaboard Air Line Railroad with Pell City’s Talladega & Coosa Valley line and Georgia Pacific Railroad (later Southern), giving the town an important rail junction. A shared depot was built, but Pell City remained largely dormant until an insurance agent from Chattanooga missed his train and had to lay over for the night.

A 1936 St. Clair Times story recounts: “On a blustery March day in 1890, a young man about 29 years of age chanced to be en route to Talladega and was to change trains at a place known as Pell City. … The young man was a guest at the Cornett House. … Looking out his window the next morning, the young man was so impressed with the natural beauty of the countryside, and it reminded him so much of the “Blue Grass” country of Kentucky, that he was interested. The young man … was Sumter Cogswell.”

A 1936 St. Clair Times story recounts: “On a blustery March day in 1890, a young man about 29 years of age chanced to be en route to Talladega and was to change trains at a place known as Pell City. … The young man was a guest at the Cornett House. … Looking out his window the next morning, the young man was so impressed with the natural beauty of the countryside, and it reminded him so much of the “Blue Grass” country of Kentucky, that he was interested. The young man … was Sumter Cogswell.”

According to records furnished by Pell City’s Kate DeGaris, Cogswell worked as an agent with North American Insurance Company, a Kentucky-based Rockefeller subsidiary. He was traveling to Talladega to meet with the Mr. Savery to discuss establishing a new NAIC agency there.

While in Talladega, he also met with Mr. Plowman, president of Pell City Land Company, which owned the town. Cogswell felt that Pell City’s three railroads, natural beauty and proximity to the Coosa River made it a natural spot for future development. Even better, the town was already up for sale.

Cogswell negotiated a two-week option to secure the property, and quickly sold it to Pell City Iron and Land Company for $50,000. They resurveyed the town, and added more housing. Hercules Pipe Company, owned by Boston capitalists, came to Pell City in 1891 to begin the town’s industrial base. Cogswell soon left town, secure in the notion that the seed he’d planted would grow and blossom naturally.

In Heritage of St. Clair County, a latter-day Lydia DeGaris writes that Sumter returned home to Chattanooga only to find that his wife had left him for his best friend. Distraught, Sumter left Chattanooga and moved to Memphis, Tenn. It was there that he would meet his future bride and Pell City’s maternal benefactor, Lydia McBain DeGaris.

Lydia was a recent widow of Charles Francis DeGaris, who was 34 years old when he and 18-year-old Lydia married. In fact, his proposal to Lydia had come as a shock to her mother, who until then had assumed Charles had been coming there to see her.

DeGaris was a well-educated, accomplished civil engineer. Their marriage lasted from 1885 until his death in 1898. They produced three sons, one of whom would actively participate in Pell City’s future. The DeGarises had designed their dream home just prior to Charles’ death. Lydia saved the plans, hoping to build it herself when things got better.

She met Sumter at one of her Uncle George Arnold’s lavish parties. Sumter was from a prominent family in Charleston, South Carolina, and had recently established a new agency in Memphis with five states under his jurisdiction. He was born on the first day of the Civil War in 1861, when Charleston’s Fort Sumter was fired upon, hence his name.

Lydia quickly abandoned her current fiancé, and married Sumter in 1900. They moved to Atlanta, where Sumter took over the management of her late husband’s sizable estate.

In 1901, Sumter revisited Pell City after a 10-year absence and found that it had almost died. In her History of St. Clair County, AL, Mattie Lou Teague Crow describes it thusly: “Upon looking from the train window, he was surprised to see a deserted village. The streets were grown up with weeds. The houses were empty, and the place had the appearance of a ghost town.” Other sources relate that goats inhabited the ground floor of the Maxwell Building.

The Panic of 1893-94 had forced both Pell City Iron & Land and Hercules Pipe Company, into receivership. According to Grace Hooter Gates, in Model City of the New South: “The firm was a failure because skilled labor would not work in Pell City, according to local stories. The iron molders would get off the train, look around and, seeing nothing but one or two stores, would climb back aboard and then ride on in search of more excitement.”

Gates continues: “Louis D. Brandeis, trustee for the company, engaged J.J. Willett of Anniston to foreclose the deed of trust for Hercules in 1893. Though the scarcity of skilled workmen in Pell City was the popular notion as to why the plant moved to Anniston, the more likely cause was the substantial savings of over 10k yearly in freights.” Brandeis won fame as a tireless advocate for consumers’ and workers’ rights, and eventually became a noted U.S. Supreme Court justice.

Lydia purchased the ruins of Pell City from Brandeis for the paltry sum of $3,000, property that had been valued at more than $50,000 less than 10 years previous. She and Sumter began nursing the failing town back to health.

According to a newspaper story, Lydia put her dream home on hold, and instead invested her wealth in Pell City. From her new holdings, she gave land for a town square to host a new courthouse after Pell City had been selected as a second county seat, 150 acres of property and an abundant spring for the building of Pell City Manufacturing Company (which later became Avondale Mills), and other acreage for a city park, schools, churches, two fraternal lodges and First Baptist Church.

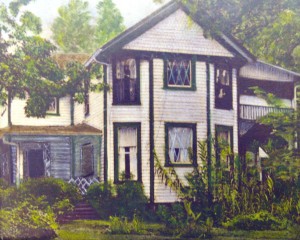

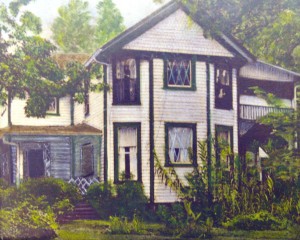

According to great-grandson Sumter DeGaris, they added three rooms to accommodate five children, plus a pantry, four porches, a servant’s house, carriage house and a large barn. Their arrival boosted Pell City’s population to 40. It is reported that they brought with them more groceries than were in the local grocery store’s entire inventory. The home they remodeled still stands today, at the corner of 18th Street and 2nd Avenue North in Pell City. It is currently occupied by Sumter DeGaris and has hosted some five generations of Cogswell/DeGaris kin.

Backed by his wife’s inheritance, Sumter quickly got down to business. He hired George W. Pratt to supervise the construction of the cotton mill. Once built, Thomas Henry Rennie of New England was hired to manage the business, whose stock soon went from less than $50 to more than $400 per share.

Next, the Cogswells founded the Bank of St. Clair County, presently known as Union State Bank, with Sumter as president and a dean’s list of local businessmen as directors, including McLane Tilton, E.J. Mintz, Arthur Draper, J. Fall Roberson of Cropwell, J.H. Moore of Coal City, Frank Lothrop of Riverside, and Lafayette Cooke of Cook Springs fame.

In 1902, Pell City faced two serious occurrences which would test its civic mettle. First, a warehouse full of dynamite and gunpowder exploded, killing several, destroying the depot, and heavily damaging several other properties. The explosives were stored in that location for use in excavating the Cook Springs railroad tunnel.

As if that weren’t enough, some citizens from “the other end of the county” approached the state Legislature, alleging that it was unconstitutional to have two official courthouses in the same county. It took years to settle this highly disruptive dispute, ending with a constitutional amendment in 1907.

Cogswell became mayor in 1903, serving for some 14 years. Sumter DeGaris tells that the town had a single saloon that provided enough tax revenue to pay for a grammar school, City Hall and numerous roads. Cogswell also served for many years on the City Council and St. Clair County Court of Commissioners.

As president of Pell City Realty Company, in 1909, Cogswell published a promotional booklet called, Keep Your (picture of eye) On Pell City, which touted everything from railroads to salubrious weather to Southern work ethic, often stretching facts to the breaking point. Quoting from that book: “The climate is simply faultless. The temperature in midwinter seldom falls as low as 30 degrees, and in the summer time rarely goes above 92 degrees. Cases of prostration from heat are unknown”.

Kate DeGaris tells that the Cogswells loved to quarter and entertain important visitors and investors in their home. A huge four-poster canopy bed was reserved for two uses only — overnight guests and having babies.

She also relates a story of how Sumter Cogswell, upon watching a poor man trudge past his home every day in bitter cold while wearing only a thin topcoat, gave him a brand new, expensive overcoat he’d received as a gift, and he kept wearing his old, tattered one.

The city flourished through World War II and beyond, with Avondale Mills supplying most of the cash flow. Lifetime resident Carolyn Hall relates that Pell City was a warm, safe place to live. While the “cotton mill” involved long hours and strenuous work, it was a welcome escape from even harder times for farmers and other locals who toiled all day for as little as a bucket of syrup.

Dr. Robert Alonzo Martin was brought to town to supervise a new hospital in the mill village, which was outside the town limits in those days. Dr. Martin became a leader in all things medical, made a lifelong career of providing quality care, and delivered some 10,000 babies to local residents. Martin Street, US 231 in Pell City, is named after him.

Pell City’s hard-working, industrious populace enjoyed many benefits from the “cotton mill,” including a fine lake, seasonal parties and every amenity a progressive company town could offer. The DeGaris descendants hosted lavish yuletide affairs, which were attended by people who had come from all over the county and beyond, mainly to sample Grandfather DeGaris’ potent eggnog (See accompanying story).

John (Jack) Annesley DeGaris, who hosted these Christmas galas in Pell City, was Lydia DeGaris’ son by previous marriage. Jack graduated Pharmacy School in Birmingham, served as pharmacist’s mate aboard a troop ship in World War I, and nearly froze in the North Sea when the ship was torpedoed.

He eventually returned home to Pell City, established Citizen Drug Company on Howard Avenue and, with the help of his wife Gertrude (Saylors), ran it successfully until his death in 1952. Jack was also a local campaign manager for Alabama Gov. Big Jim Folsom.

Jack’s son, Annesley H. DeGaris, writes in Heritage of St. Clair County: “… (Jack) was one of the best civic workers Pell City ever had. For many years, Jack gave a banquet for the football players, cheerleaders and coach as invited guests. Also, one day each year, Jack let the high school senior class operate the soda fountain in his drugstore, taking all the proceeds to help with their school trip. The Citizen Drug Store was always referred to as ‘the drug store in the middle of the block’ at 1907 Cogswell. …”

Lydia never got to build her dream home, but she and Sumter presided over a dream city of their own making. They’re an indelible part of St. Clair history. Pell City’s Howard Avenue was re-named in their honor after his death.

Longtime business associate McLane Tilton penned an appropriate epitaph for his dear friend Sumter:

His life all good,

No deed for show; no deed to hide,

He never caused a tear to flow

Save when he died.

To learn how they made enough eggnog for most of the town in a washing machine, check out the full edition of the December 2012-January 2013 edition of Discover The Essence of St. Clair.

Story by Carol Pappas

Story by Carol Pappas It was much the same in her own family. Her mother was a survivor. Her husband Jimmy beat the odds, too. At the Pink Fundraiser, she is surrounded by friends who know firsthand what rising above the challenge means. “It’s a little sisterhood — someone to talk to who knows exactly what you’re going through.”

It was much the same in her own family. Her mother was a survivor. Her husband Jimmy beat the odds, too. At the Pink Fundraiser, she is surrounded by friends who know firsthand what rising above the challenge means. “It’s a little sisterhood — someone to talk to who knows exactly what you’re going through.”