Storied final resting place piques interest

Story by Joe Whitten

Submitted photos

Just north of Odenville, in the sheltering earth of Liberty Cemetery, repose the remains of some of St. Clair County’s early settlers in Beaver Valley.

The cemetery rises in gentle slopes to the left, right and rear of the circa-1850 church building. Frank Watson’s survey of the cemetery lists the names and dates for 22 people who were born more than 200 years ago. Of those 22, nine were born in the 18th Century.

Old newspaper articles record that early in the 1820s, worship services were held on the site where Liberty Church stands today. The first building, a log structure, served as a community church. In 1835, Rev. James Guthrie organized a Cumberland Presbyterian Church there. The church remained Liberty Cumberland Presbyterian Church until near the end of the 20th Century, when it once again became a community church. Local tradition states the present building was constructed around 1850, and the style of its architecture gives credence to that date. Frank Watson’s cemetery survey shows the first burial occurred in 1833.

The earliest Beaver Valley settlers buried in Liberty Cemetery are John Ash (1783-1872) and wife, Margaret Newton Ash (1795-1855). John, Margaret and her parents, Thomas and Ann Newton, had joined a westward bound caravan that had progressed into Alabama Territory in 1817. The caravan had camped in the vicinity that would later be south of Ashville on today’s US 411.

Betsy Ann Ash was in a horse-drawn wagon when one of the men shot at a turkey. The horse bolted at the shot, causing Betsy Ann to fall from the wagon, breaking her neck. The Ash and Newton families, feeling they could not leave the grave of Betsy Ann and continue west, scouted out the valley. Finding the area a commodious land, the families bid farewell to the westward caravan, and settled in what would become St. Clair County, Alabama.

John Ash and his father-in-law, Thomas Newton, constructed, within sight of Betsy Ann’s grave, a log cabin to live in as they settled in this land. That 1817 structure remains today as the oldest house in St. Clair County. The next year, John Ash built his own home.

Written accounts state that in 1818, not too far distant from the Newton cabin, John built a log home. As years went by, John added to the home, encasing the log home within the new. He planked over the inside log walls, making the home more fashionable. Although in need of restoration today, the home still stands and is on the Alabama Register of Landmarks and Heritage and the National Register of Historic Places.

John Ash helped establish St. Clair County and participated in both local and state affairs, serving as a county judge and member of the first Alabama State Senate. The town of Ashville honors John Ash by bearing his name.

John and Margaret Ash are buried side-by-side at Liberty, but they are memorialized with modern markers. The original ledger-style stones covering the entire grave were removed to Ashville. Though broken, they survived and lie in a place of honor at Ashville City Hall.

Henry Looney (1797-1876) and his father, John, came through what would be St. Clair County in 1813 as Tennessee volunteers with Andrew Jackson, who had come to subdue Native-American uprisings. Along with Jackson and his men, they helped construct Ft. Strother and fought with Jackson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend.

After the Indian Wars concluded, John Looney and wife, Rebecca, moved their family to Alabama in 1817. Originally intending to settle on the east side of the Coosa River, they changed plans after learning the Creeks still controlled lands east of the Coosa and chose to settle on the west side in today’s Beaver Valley. Old record books show that John recorded two forties (40 acres), and in 1818, he and sons Henry, Jack and Asa set to work building a log home.

In a brochure titled, “The Henry Looney House,” Mattie Lou Teague Crow described the process of building: “Trees were cut, squared, notched and hauled to the building site. Stones for the foundation were quarried from the mountainside and creek bed. Bricks for chimneys were molded and baked. Shingles were rived and stacked to dry. Late in the year, the family left their wagons and lean-tos and took up residency in their new home.”

Winter moved into spring, and the rains came, swelling the creek and flooding the home. After the flood, mosquitoes invaded and several family members suffered from chills and fever. John Looney realized he’d chosen the wrong location. So, he and the boys dismantled the home and hauled the logs to higher ground and reconstructed it.

The house stands today, thanks to Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Creitz, who donated the home and plot of ground to the St. Clair Historical Society, which supervised the restoration of the home and operates it today as a museum.

After his father’s death in 1827, Henry became head of the family. In 1838, Henry married Jane Rutherford Ash, daughter of John Ash. They continued living in the home, and it became known as the “Henry Looney Home.” It stands today as a treasure for both Alabama and St. Clair County, for it is the only surviving double-dog trot pioneer home still standing in our state.

Henry Looney died in 1876 and is buried at Liberty. After his death, his wife moved to Texas, where she died in 1901.

Settling Odenville

Methodist minister Christopher Vandegrift (1773-1844) and wife, Rebecca Amberson Vandegrift (1777-1852), left Chester County, South Carolina, in 1821 and migrated westward. While stopping for rest in Jasper County, Georgia, their daughter, Ellen (1800-1853), met a young man, Peter Hardin (1803-1887). They fell in love and wished to marry. Christopher agreed to the marriage if Peter would join their caravan. Love won, and the westward trek progressed into today’s Odenville, where the Vandegrifts and Hardins settled in December 1821. Both Christopher and Peter constructed homes where they settled.

The Vandegrifts became leaders in community and church. In 1835, Christopher served as an elder in the organization of Liberty Cumberland Presbyterian Church. In today’s Odenville Presbyterian Church, Christopher’s descendants worship and serve there, continuing the godly influence of their ancestors.

The Vandegrifts became leaders in community and church. In 1835, Christopher served as an elder in the organization of Liberty Cumberland Presbyterian Church. In today’s Odenville Presbyterian Church, Christopher’s descendants worship and serve there, continuing the godly influence of their ancestors.

Peter Hardin constructed a log home in 1824, which was lived in by his descendants until 1975. Nell Hardin Hodges was the last Hardin to live there. The home, which had been added to over the years, remained standing until 1990. Today a church and a store now occupy the property where the cabin stood for 166 years.

The area where Peter settled came to be called Hardin’s Shop. He established two businesses, a blacksmithery and a cabinet shop. A few items from both remain in Odenville. In addition to the businesses, Peter was a Cumberland Presbyterian minister, having been ordained Jan. 3, 1850. He is on record as having preached the first sermon in the circa-1850 Liberty Church building still in use today.

Peter Hardin died in 1887. Myrtle Maddox Kinney, whose father would have known Peter, said in a 1990 interview that Peter had gone to the field to pull corn. When the wagon was loaded, he started back and “…somehow or another, the horses turned the wagon over and the load of corn fell on him and killed him. He was up there by himself.”

The Southern Aegis reported Peter’s death in the Nov. 30, 1887, issue. Then in the Aug. 9, 1888, issue it announced: “The funeral of Mr. Peter Hardin will be preached by Rev. A.B. Wilson of Branchville, assisted by Rev. G.F. Boyd, on the second Sabbath of August. …” Often in those days, a body would be buried, but the funeral not be preached until the next Sunday the circuit-riding preacher came to town, usually no more than three weeks after the burial. This was eight months after Peter’s death. The puzzle was unknotted by a descendant living in Sunflower Mississippi, who recognized the Rev. G.F. Boyd as Peter’s cousin. The family had waited until Rev. Boyd could come from another state to preach the funeral.

The first brick house in St. Clair County was constructed by Obadiah Mize (1780-1852). Obadiah and wife, Sarah Frazier Mize (1789-1855), probably came into St. Clair County shortly after the Hardins and Vandegrifts, for he settled not too far from their homes.

According to a file in the Ashville Museum and Archives, the brick house is described in some 1932 notes. “Mr. Mize built this two-story home, consisting of six rooms on the first floor and three on the second, of brick which were made there on the lot of the building.”

In a photograph belonging to Frank Watson, you can see the bricks were laid Flemish bond rather than the more ordinary American bond. In Teresa Morris’ notes from an interview conducted in the 1970s, she writes, “In 1830, Mr. Mize built a two-story brick home … on the property which fronted Old Montevallo Road, and this house, known as ‘The Old Brick’, remained a landmark until it was demolished in 1930.”

When The Old Brick was demolished, the owners constructed a wood-frame home on the stone foundation of the old house. That house remains occupied today. They used the bricks to construct a retaining wall near the highway. The Fortson Museum in Odenville displays a brick from the house.

All in the family

Israel Pickens Hardwick was born in 1813 in Jasper County, Georgia. Roland Holcomb wrote about Pickens in A Hardwick Family Tree that Pickens’ sisters, Lydia and Susan, married Vandegrift brothers, John and William. But the Vandegrift brothers had no sister for Pickens to wed. No problem – he just waited 30 years until the third brother, Jim Vandegrift, had a daughter who was old enough to marry. Therefore in 1863, at the age of 50, he married Jim’s daughter, Nancy Ellen Vandegrift, age 17. He came safely through the Civil War and outlived his wife and all his contemporaries. In 1923, at age 110, Israel Pickens Hardwick “was gathered to his fathers” and was laid to rest at Liberty.

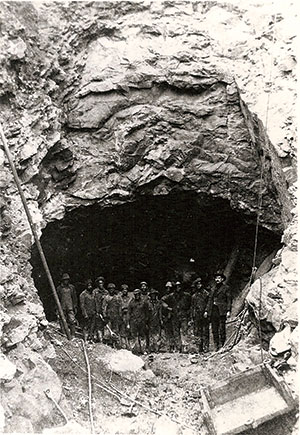

The origin of Hardwick Tunnel

Pickens served in Company C, 18th Infantry Regiment, Confederate States of America. Roland Holcomb recounts a Pickens’ story that happened when the railroad was being put through Odenville very early in the 20th Century. He had given the Seaboard Airline the land and rights to build a tunnel through the mountain as long as the tunnel be called Hardwick and that the train would stop there. Seaboard Airline agreed.

Pickens served in Company C, 18th Infantry Regiment, Confederate States of America. Roland Holcomb recounts a Pickens’ story that happened when the railroad was being put through Odenville very early in the 20th Century. He had given the Seaboard Airline the land and rights to build a tunnel through the mountain as long as the tunnel be called Hardwick and that the train would stop there. Seaboard Airline agreed.

Holcomb writes, “He (Pickens) frequently dined with the tunnel construction crews who were billeted on the right-of-way near his home. One evening, a visiting railroad supervisor from the North made some remark about the South that angered the old man.

“While he said nothing, he got up and left the table. He returned a short time later with his rifle, prepared, as he said later, to demonstrate that the Army taught him well how to shoot Yankees. Fortunately, some of the local men on the crew, who knew the old man and recognized the signs, had spirited the visitor away.” Such was Israel Pickens Hardwick.

Lost at sea, but not forgotten

One marked grave has no body buried there. The stone, for the son of Louis and Marze Forman, reads: “Forman Austen Mize / Feb 13, 1900 / Lost on USS Cyclops / March 1918 / Gone but not forgotten / Son.”

The Cyclops was launched in 1910, and when the United States entered World War I, it was commissioned in 1917 for military use. In February 1918, loaded with manganese, she departed Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, bound for Baltimore. She stopped in Barbados, then sailed on.

Her last sighting, according to accounts, was March 9, 1918. Sailing into the area known as the Bermuda Triangle, the Cyclops vanished, and as author Jerry Smith records in Uniquely St. Clair “… no distress call or other message was heard on the wireless. Nor was a single body or piece of wreckage or artifact ever found.”

By some accounts, the ship had been overloaded in Brazil and when it encountered turbulent sea weather in the Triangle, it could not survive and sank. Others propose that a German submarine torpedoed it or that Germans captured the ship. Or did the Bermuda Triangle swallow it? Some consider that theory outlandish, others not.

Family tree yields university president

The Rev. James Benjamin Stovall (1868-1917), a beloved Presbyterian minister, not only pastored churches in St. Clair County, but was also president of Spring Lake College in Springville.

In 1915, he accepted the call to pastor Brent Presbyterian Church. He died there in 1917 when, as recorded in the History of Brent Baptist Church, by Sybil McKinley, “He was standing in the back of the wagon holding on to a cabinet being moved, when the horse lurched forward throwing him off and pulling the cabinet down on top of him.” His wife, Effie Fowler Stovall (1873-1970), continued living in Brent, raising her children there and becoming a guiding light to the community.

James and Effie’s daughter, Chamintey “Mittie” Stovall, married Ralph Thomas, an educator. Their son, Joab Thomas, attended Harvard, earning undergraduate and graduate degrees in biological sciences. Well respected among colleges and universities, Dr. Joab Thomas served as chancellor of North Carolina State University and as president of the University of Alabama and of Pennsylvania State University.

The earliest Stovall date in the cemetery is that of Matriarch Sarah Stovall (1791-1858). She reposes with numerous other Stovalls in Liberty Cemetery. Sarah’s husband, Benjamin, died in Jefferson County and is buried there

Three-shot suicide?

The marker at the grave of R.M. Steed (1828-1899) causes no one to pause and ponder. However, his reported death in The Southern Aegis, Feb. 8, 1899, brings the reader to a sudden stop. It reads: “Richard M. Stead [corrected the next week to ‘Richmond Steed’], residing near Odenville, St. Clair county, on Monday the 6th inst., committed suicide by shooting himself three times.

“The deceased was well known in the county, having been born and raised here. He was about 73 years of age, was a farmer of sturdy habits and had been in a depressed state of mind for some time. During the war he had been a soldier in the federal army, and the weapon used in his own death was an army revolver he brought home at the close of the war and had preserved ever since as a relic of the war.”

In 1994, someone with Steed connections read the above and commented that the family always doubted his death to be suicide. A three-shot suicide does stretch the imagination.

Final resting place indeed

Some of those buried in Liberty Cemetery influenced the establishing of St. Clair County and have left names and influence well-etched into her history. Most lived unassuming lives, nurtured home and children, and left their names etched upon hearts and lives.

In the end, relentless Death gathers all to a final resting place—equality in mortality. Thomas Gray expressed it well in his “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.”

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power

And all that beauty, all that wealth ever gave,

Awaits alike the inevitable hour,

The paths of glory lead only to the grave.