Dry cleaner escaped Holocaust, traveled storied route to Ashville

Story by Joe Whitten

Submitted photos

For Bernie Echt, the journey from Gross Kuhren, Germany, to Ashville, Alabama, included stops in Africa, China, the Dominican Republic and sojourns in various cities in the United States.

Bernie’s parents, Solomon and Erna Czanitsky Echt, already had daughters Ruth and Eva when Bernie was born on Nov. 4, 1937. Sister Sarah would arrive Nov. 4, 1938.

His parents and grandparents owned a farm in Gross Kuhren and dealt in horses and cattle. Although Jewish, they conducted business with both locals and the German military before the war.

Relations seemed good with people in the area, for as Bernie recalled, “My parents and grandparents had lots of connections; that’s why we are still here. Otherwise we would be …,” he let those words hang, then added, “They helped us to get the hell out of there.”

Bernie wasn’t yet a year old when they fled the Nazis, so he recounts what he was told by relatives. In spite of the apparent good relationship, “At the end of 1937 or the beginning of 1938, one evening, they knocked on the door, and calling Solomon by his nickname, they said, ‘Sally, you need to go with us down to headquarters.’”

Solomon and Erna both asked for a reason, but the only answer they got was, “We can’t tell the reason; you just need to go with us. You don’t have to take nothing along.”

Erna asked where they were going, and they replied, “To town.”

“It was the Gestapo,” Bernie continued. “They took him to the concentration camp, Sachsenhausen, and put him to work in the stone quarry. He was in there until the end of ’38, or thereabout.”

Bernie is unsure of how this happened, but his mother and grandparents paid off certain Nazi officers to get Solomon out of Sachsenhausen. He believes they gave money and cattle, and that one of the officers was a close friend who used to visit on Sunday afternoons.

The officers warned that Solomon must disappear immediately, so within 24 hours of release, he was on a freighter to Shanghai, China. He lived in Shanghai a year before Erna and the children could journey there.

And what a journey Erna and the children had getting to Solomon in China. The grandparents hoped to emigrate to Palestine, but borders closed before they could leave. They never got out.

Along with other Jews, Erna and the children secured passage to China on an Italian freighter. Difficulties arose at the Suez Canal when authorities refused the freighter permission to proceed.

Low on fuel and food, the ship diverted to an African island where it languished for six months. A Jewish organization managed to get money to the captain so he could continue to China.

Finally, in 1939, Erna and children joined Solomon, where he worked on a missionary farm in Shanghai.

Because of the Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), the Japanese occupied Shanghai. For the moment, things seemed peaceful. “The Japanese soldiers would come to the house,” Bernie remembered, “and my mother would cook them something. They had a good time.”

Concentration camp

All that ended Dec.7, 1941 – Pearl Harbor. “The Japanese came for us,” Bernie remembers, “put us up on a truck and took us to a camp. They took our passports. Everything. We had just the clothes we wore.”

There were 2,000 in this Japanese concentration camp with 16 people to a room. They devised privacy curtains with the bed blankets during the day, then took them down for cover at night.

The rabbis in the camp made sure Jewish boys received religious instructions. Going and coming from the place of instruction had its dangers, as Bernie recalls one night: “I remember rabbi took us one evening to the main building there, and the Japanese were shooting the guns with light-balls to light up the streets inside the camp, so they could see if anybody was walking around. And the rabbi said to us, ‘Just stand against the wall and don’t move.’ That’s what we did, and that’s how we always got through.”

The rabbis made sure that the kids who went to temple had kosher food for Passover, a sacred necessity for Orthodox Jews, such as the Echts.

World War II ended, and liberation finally followed. Bernie recalled, “McArthur came, and the streets were full of military. The Japanese commander who mistreated so many – he didn’t do it personally, but he had command over it – the teenage boys in the camp went to the Japanese headquarters, got the commander out, brought him to the camp and got sticks and hit him.”

Bernie didn’t participate in that. “That wasn’t my idea. I couldn’t join in beating him. He was only a man. I look at things a little bit different. I shouldn’t, maybe, but I do. A human being is a human being.”

The American nurses took the internees into the country, gave them food, and American military doctors gave physical exams.

The Americans taught them songs, Bernie recalled. “The first song we learned was ‘God Bless America,’ and then we learned the military songs – the Navy song and ‘This is the Army, Mr. Brown.’” He laughed and added, “We changed that one a little bit.”

Wanting to leave China, Bernie’s family went to the consulate and asked about being able to come to the United States. A Jewish organization (American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee) took over and organized the Echts’ and others’ exodus. They left for San Francisco on the Marine Lynx, an American transport ship. “We sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge, and it was wonderful,” Bernie said. “I was 9 or 10 years old.”

In San Francisco, the family stayed quarantined in a hotel for six weeks. Bernie recalls that the Jewish organization fed them and took them to a clothing store and bought them garments and shoes. He got his first pair of long pants and pair of shoes.

Dominican Republic

When the quarantine ended, the Jewish Distribution Committee came to tell the Echts the three countries available for relocation: Australia, Canada and the Dominican Republic. The family chose the Dominican Republic.

As early as 1938, General Truijillo of the Dominican Republic offered to the Jewish organization refuge to as many as 100,000 Jews fleeing Germany. On the north coast, now Sosua, General Trujillo set aside a large section of wooded land, and the Dominican Republic Settlement Association (DORSA), a Jewish group, cleared land and erected barracks. “It was similar to a Kibbutz,” Bernie said. “They all ate together, and the women did everybody’s laundry. There wasn’t that much that each one had separate.”

DORSA built houses on plots of land, families with kids got the first houses built, then couples without children. To get them started, for the father of the family, DORSA gave 10 cows; for the mother, six; and for each child, one. A family paid so much a month to DORSA until they had paid for the farm, house and livestock.

The Echts lived on one of the DORSA farms until Bernie’s mother died in 1949. After her death, Solomon left the farm and moved the family to the city. When Bernie turned 13, his father and sisters arranged his bar mitzvah. “I learned all the rituals,” he said. “I already knew a big part of it. I was very orthodox when I started out. Very orthodox until my mother died, then I slowly let it go.”

Home-life deteriorated for Bernie after his mother died, and a few months after his 13th birthday, he set out on his own. He had only the clothing he wore and no money.

He went to the Jewish organization in Sosua, met with the administrator, and told him about leaving home and needing a job. The administrator told Bernie he had no job for him because he lacked education and job skills.

Unsuccessful there but undaunted, he made his way to the farmers’ cooperative and told them his predicament. “I need a job. I need something to do to make a living.”

They listened to him, then, offered him the only available job, cleaning the animal intestines in the slaughterhouse, which paid $25 a month.

Bernie took the job. He lived in a barrack room for $3 a month, which included electricity and water. He commented, “I earned $25, paid $3 for lodging, and had $22 left. I didn’t need nothing.”

Work ethic rescues him

Although he started with a nasty job in the slaughterhouse, Bernie worked hard, and that served him well. The manager of the meatpacking plant soon took him out of the slaughterhouse and taught him about choppers and carvers. Mr. Meyerstein, who had worked for Armour and Swift in Chicago, taught him how to make sausage.

A careful observer and fast learner, Bernie said, “When I saw anybody doing something I wanted to learn. I caught it with my eyes and remembered it. I had no other choice. There was no Social Security, no unemployment, no insurance. Nothing. I had to learn.”

Management liked Bernie’s work ethic and raised his salary to $45 a month. He saved $10 a month until he had about $30 put aside. Then he went to a farmer to buy a calf. When the farmer found he had the money, he asked where he would keep the calf, and Bernie bargained with the farmer to pasture the calf for $1 a month.

They both agreed that when the calf became a milk producer, the milk belonged to the farmer, but calves born to those cows belonged to Bernie.

Next stop: USA

In 1957, when Bernie came to the United States, he was earning $85 a month and had 12 head of cattle, which he sold to finance his trip to the States and for Washington’s required $300 security deposit in case his job fell through.

Some Marines were the first who tried to help Bernie get to the United States. They said if he were willing to join the military, they would help him join the Marines. Bernie was willing, but the Marines weren’t – he was 2 inches too short at 5 feet, 5 inches tall.

Regulation height was 5 feet, 7 inches tall.

However, when a Mr. Weinberg came over from New York City, Bernie had success. He asked Weinberg if there was a newspaper in New York where he could run an ad for work in the United States. Yes, there was, the Aufbau, published in New York City for the German Jewish Club. Weinberg placed the ad: “Young butcher looking for a job in the U.S.”

Bernie waited. Then a letter from a Mr. Krucker arrived at the consulate in the Dominican Republic. Mr. Krucker owned a Swiss restaurant in Pagona, N.Y., and needed a butcher there by May 27, no later.

Bernie leapt into action. A visit to the consulate produced a list of “must do” things in order to leave. He took the list and returned in two days with everything else on the list.

Then he needed a “quota number,” but the consulate said that would take two weeks, and that would be too late to make it to New York by May 27.

Bernie tells it best. “It was hard to get out of the Dominican Republic at that time. Because of Nazi persecution, I was stateless – no passport. All I had was an ID from the Dominican government, like a driver’s license, but not a driver’s license.”

Bernie had to be in New York by May 27, so he begged the consulate to call Washington and get a quota number. “I will pay for the call,” Bernie said.

The consulate said, ‘Are you serious? We don’t do that normally.’ But with a little more pleading from Bernie, he said, ‘All right. Go outside and sit and wait. I’ll let you know. I can’t promise you.’

Bernie waited an hour and a half before the consulate came out and said, ‘I can’t believe it. I got you a quota number. Everything’s ready. Go to the airport and get yourself a ticket and you’re ready to go.’

Then, another problem loomed. Bernie had no passport, but he knew who could help. A German Jew named Kicheimer could work miracles almost. Bernie told Kicheimer why he was in a rush and gave him his paperwork.

Kicheimer returned the next day with the necessary documents, and Bernie was ready to leave. At the airport, Ruth and Eva were crying, afraid of what the police would do if they found out how he’d gotten his documentation. Bernie told them, “I did nothing; the man did everything. I’ve got a legal piece of paper.” He laughs and adds, “I was so glad when that plane went up and I looked down.” He was on his way to a new life that one day would land him in Ashville.

When Bernie arrived at the restaurant, Mr. Krucker gave him a place to stay in his hunting shack, telling him to unpack, come to the restaurant and eat, then rest for the next day when they both would go to New York City to buy fish, meat and vegetables for the restaurant.

Bernie spoke of Mr. Krucker’s kindness to him, saying, “He treated me like I was his son. He was very good to me. When I bought my first business, he co-signed the loan for me.” Bernie’s respect for Mr. Krucker was evident when Krucker asked him not to wear his David Star because it made some German patrons uncomfortable. Bernie removed it, saying, “Mr. Krucker, I am Jewish in my heart, I don’t have to show it.”

Saying, ‘I do’

The restaurant’s head waitress, Pia, was a German gentile in an unhappy war-bride marriage that would end in a divorce. She was 10 years older than Bernie, but age presented no problem to him, and a few years later she became his wife. She converted to Judaism, going through the counseling sessions with the rabbis.

This was important to Orthodox Jews for descent is traced through the mother and gives both male and female children irrevocable Jewish status. It was a happy marriage that held strong until Pia died of brain cancer in 1979. The couple had three children: Bernhard “Bernie” Jr., Daniel and Katharina.

Mr. Krucker had urged Bernie to ask Pia out. He was reluctant to do that because of lack of money. Pia knew this and said, “This time, I will buy you a root beer float and a hamburger. If you did have money, I don’t want you to spend it. You are new here, and you need to save your money.”

They didn’t go out again until Bernie had saved up some money. Mr. Krucker knew this and came to Bernie and gave him an envelope and said, “That’s for you.” It contained his $50 weekly pay, inside. “I was rich,” Bernie said.

Never afraid of hard work, Bernie worked in the restaurant through the summer and into the fall, and when the number of diners dropped, Bernie got a job in the meatpacking plant in Mazzolas, N.Y., earning $65 a week. When he got off work there, if an auction was being held, he would sell hamburgers at the auction house. “You know, a couple of bucks here and there, and I made money,” he said. On Saturday and Sunday, he worked at the restaurant.

Bernie and Pia were engaged now, and he wanted more income. One day he asked the man who picked up and delivered the restaurant’s laundry if there were money to be made in laundry work. He told him, “If you work hard you can make money. It’s on a percentage of what you collect.”

So, Bernie went to see the owner, Frank Senatores, who told him, “I don’t pay until you bring in work. You deliver it and collect, and I pay you a commission on that. You have to use your own car. I don’t supply no vans or anything.” Bernie accepted the job.

Making of an entrepreneur

He worked hard – and so did Pia. After working his dayshift at the meatpacking plant, he and Pia would run the laundry and dry cleaning routes until about 8 p.m. Pia would drive, and he ran to the houses delivering and picking up. “I’ve been doing that for 60 years,” Bernie said recently. “The same system. And it works. Believe me, it works.” They built up a good route and eventually bought the drop business.

In another village, he saw a laundry and dry cleaner that wasn’t doing well because of the lazy owner. Obtaining a bank loan, Bernie bought that company and gave up the restaurant job to concentrate on the laundry business.

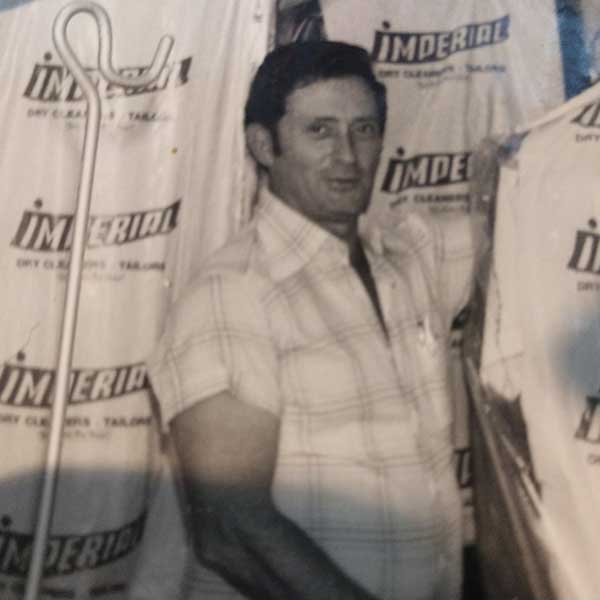

Always the quick and thorough learner, Bernie learned the dry cleaning and laundry business hands-on. He bought a 1952 Chevrolet truck van, put hanging racks inside, and had a high school art student paint the truck white with a crown for Imperial Laundry and Drycleaners, with the address and phone number.

From the beginning, Bernie has never turned down a challenge, for he’s always assumed he could do it. Early on, a man came in with a wide lapel, double-breasted suit wanting Bernie to cut the lapels down to a narrower size. Although he had never done alterations before, Bernie said, “We can do that, but it will cost you.”

Pia thought he was crazy, but Bernie said, “Don’t get excited. We have a suit hanging here. I’ll lay it on top of the one to alter, mark all around the lapel but leave a half inch. Then we’ll cut the material off and turn the rest under and sew it.” They did, and the customer was so happy he gave them a generous tip. After that, Pia learned to do whatever alterations that were needed.

By the time Pia died of cancer, they were living in Florida, and Bernie had expanded into selling laundry and dry cleaning equipment.

Five years after Pia’s death, Bernie exhibited his machines at a convention in Atlanta. One evening after the exhibits closed for the night, Bernie went to eat a restaurant where there was dancing. There he met Doan, who was buying merchandise for her dress shop in Springville, Alabama.

The magic of dance

She and Bernie danced that evening, and that dance blossomed into a courtship that resulted in a wedding the next year, 1985. The love affair has lasted 35 years. Although Doan didn’t convert to Judaism, she attends temple with Bernie.

It was Doan’s St. Clair County roots that brought them to Ashville and the establishing of Imperial Laundry and Professional Drycleaners there in 1994. Their pickup and delivery routes extend into Jackson and Cherokee counties. Bernie’s original method of building a business by meeting and knowing his customers still holds him in good stead today.

Katharina Echt says of her father, “My brothers and I were raised with a strong foundation of what it means to work hard. We each have a keen understanding, by our father’s example, of what is possible with sheer will and determination. Ever present is his steadfast belief in our ability to achieve anything we set our minds to. And so we have.”

Bernie never lost hope or purpose in the face of hardship, adversity or tragedy. He has focused on the good of life rather than the bad and remains a cheerful man who is a delight to know.

Stop by and say hello. You’ll enjoy meeting him.