Master storyteller gets ‘schooled’ on Chandler Mountain

Story by Carol Pappas

Story by Carol Pappas

Photos by Jerry Martin

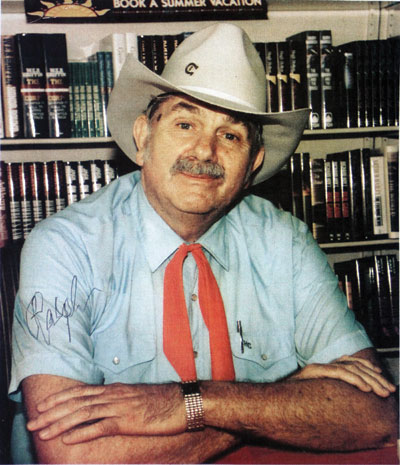

In 1974, Dolores Hydock was on a hunt for folklore for an in-depth paper she was researching for a college class at Yale University.

That unlikely journey from New Haven, Conn., led her up a winding mountain road in northeast Alabama and clear up on the top, she found what she was looking for and some things she never dreamed she would find.

As a student in American Studies, this city girl born and raised in the north, set her sights on the Deep South for a paper on Alabama folklore. Recounting her early planning efforts, she said she traveled across the state and “discovered everything from Mardi Gras to snake handling.”

Alabama’s folklore was so abundant and so diverse, she faced the dilemma of having to narrow her focus. Enter Warren Musgrove, who owned Horse Pens 40 on Chandler Mountain at the time. She had been encouraged to go and see him because of his gift for storytelling and his ability to recognize where the best folklore could be found — right where she was — on Chandler Mountain.

For four months, she lived among its people, developing special relationships that would draw her back to the state after college and put her on a road that led to her life as one of Alabama’s master storytellers.

On her CD, Footprint on the Sky: Memories of a Chandler Mountain Spring, Hydock vividly recounts the people and the places atop the mountain. On the CD and in person, she talks fondly of those months, especially centering around two special friends — Hazel Coffman and Dora Gilliland.

She talks of their impact — just like people who make a difference in your life, people who are “not powerful but are strong; not wealthy but are generous; not famous but are loved.”

They are, she said, people who “work hard, live simply, love their families and make strangers feel at home.” Just like Hazel and Dora did for a college girl from up north in 1974.

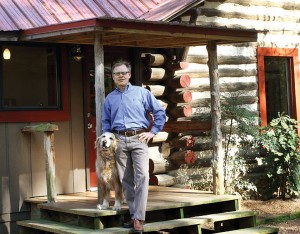

Hydock traveled the snaky road leading to the top of Chandler Mountain with Discover, revisiting some of the places and remembrances that helped shape the story performer and actress she is today.

Her wit, charm and an innate ability to turn a phrase in any direction she wants it to go are simply part of her signature style on stage, much to the delight of audiences large and small.

She is the most requested Road Scholar, a program of the Alabama Humanities Foundations that provides top-notch speakers for libraries and historical groups across the state.

And she is an award winning story performer with national accolades to her credit.

She has taken many an audience back in time to her Chandler Mountain spring, a time of seemingly endless learning for this Ivy Leaguer, the kind of lessons you just can’t get from books.

She has taken many an audience back in time to her Chandler Mountain spring, a time of seemingly endless learning for this Ivy Leaguer, the kind of lessons you just can’t get from books.

With a twang in an accent familiar around these parts, she lets audiences know some of the lighter lessons learned there: “Sand Mountain tomatoes are the most famous, but anyone who knew tomatoes knew Chandler Mountain tomatoes were the best.”

If you’re mountainfolks, it’s “on the mountain and off the mountain,” no going up or down.

That spring, she stayed at the Clarence House, a place used only in the summertime for tomato growing season. It had no electricity — only a fireplace to keep her warm.

There, she learned her first lesson. Those “long pointed sticks” piled behind the house were not kindling left by a thoughtful landlady, they were tomato stakes, which she learned after burning a whole stack of them her first week on the mountain.

At Rogers Bros. Store, whose sign advertised “feed, seed, hardware, groceries and gas,” she learned a little more. She had a ringside seat, a crate bench by a wood burning stove where people gathered to “tell stories and a lie or two,” she says.

She talks of their patience when a language barrier seemed to get in her way.

“You ever warm up?,” a woman asked her. Not knowing if she was referring to the weather or her demeanor, she was rescued when Hazel Coffman sensed her panic and stepped in to save the day. “She’s asking you do you ever eat leftovers, you know, warm up? She’s inviting you to dinner, honey, if you’ll eat what she has.”

With an obvious debt of gratitude, Hydock says, “Hazel and Dora Gilliland took me in — helped me understand you might come to Alabama looking for folklore but if you give it half a chance, odds were really good you’d end up finding a home.”

And that she did, moving to Alabama that same year after graduation.

She credits Hazel with unlocking her storytelling ability in later years with an iconic image of her — one leg shorter than the other making her “tilt” when she walked. Dressed in a bonnet, galoshes and overalls, she would scatter feed through the yard for dozens of chickens, calves, cows, a dog and a one-eyed cat. “Come on babies,” Hazel would call.

It didn’t matter that it wasn’t easy to get around, there are “plenty ways of doing things if you want to,” Hazel told her.

“Come on babies,” she calls as they scurry toward her. “I hold this picture of her in my heart,” says Hydock.

In her stories, Hydock talks about the old Chandler Mountain Community Center. It’s closed now, but it once was a thriving gathering place, especially for the women who came to quilt and visit every Tuesday and Thursday.

It was there she made it over another language barrier. What is afternoon to some is strictly evening up on the mountain. “When you’re up at first light and don’t know anything after 8 when you go to bed, anything after noon is evening,” she was told.

How did they learn to quilt so well? “Grow up in a house where you can see through the cracks in the floor, and you know it gets plenty cold in the wintertime.” With five or six kids in a house, “You learn to make them pretty quick.”

Hazel’s best friend was Dora, who Hydock describes as having a high, funny laugh. “Everything just tickles her to death.”

Dora would offer tales of her Aunt Bertie who used to tell scary stories. Dora admitted they did scare her in her early years but as she grew older, she learned not to be so afraid.

One time, Dora told her, Aunt Bertie started one of her stories, saying a man without a head got in bed with her and Uncle Carl.

A sensible Dora stopped her right there. “A man with no head may have gotten in bed where I had been, but not in bed where I was. Imagine a man with no head getting in the bed with you.”

Hazel sold bonnets every year at the bluegrass and crafts festivals held at Horse Pens every fall and spring. She had the first booth next to the music stage, selling the bonnets she made. “She sold hundreds every year. Dora sold handmade quilts.” They were part of what made those festivals a featured state attraction every year.

In later years, Hazel moved to the city, Gadsden, and lived there 14 years before she passed away. Dora stayed on the mountain — “canning and quilting,” Hydock says. She was 96 when she died.

Those two special ladies, Hydock tells her audiences, may be people you know or you know someone just like them. “They live on in the memories of people whose lives they touched and the people who love them.”

And they live on in the stories Hydock tells about a spring spent on a mountaintop and a place where she found a home.