World’s Greatest Archer

World’s Greatest Archer

Story by Jerry C. Smith

Photography by Wallace Bromberg Jr.

Submitted photos

Schoolboys often dream of marrying a favorite teacher, but Howard Hill of Shelby County actually pulled it off and, with her help and support, became a true legend in his own time, the World’s Greatest Archer.

Ashville’s Elizabeth Hodges had taught high school English in Wilsonville, Alabama, where Howard attended. Apparently their attraction was mutual, as he married her a few years later. They had a long, storybook life together, and now lie in final rest beside each other in Ashville’s New Cemetery.

Born in 1899 on a cotton plantation in Shelby County, Howard’s father made archery equipment for him and his four brothers and taught the boys how to use them. Howard grew up using weapons of all kinds, but his bow was always his favorite.

According to Craig Ekin in his book, Howard Hill, The Man And The Legend, Howard killed his first rabbit at age five and, in his excitement to show his folks the game he’d brought home for supper, left his bow in a cotton field. It took three days to find it.

Howard entered Auburn’s veterinary school at age 19, but did so well in sports that animal medicine was soon sidelined. A tall, powerful young man who excelled at anything athletic, he lettered in baseball, basketball and football, earning the nickname of Wild Cat.

Howard didn’t neglect his archery interests while at school, often slipping away on weekends for long target practice sessions which, according to Ekin, usually involved shooting some 700 to 800 arrows. Howard was so appreciative of his years at Auburn that he created a college archery program at the school after his retirement. Many of his artifacts are now displayed on campus.

In 1922, Howard moved into Southern League semi-pro baseball, often playing pro golf in off-season. It was about this time that he married Elizabeth, which Ekin describes as the best move Howard ever made. “Libba,” as he called her, realized from the start that archery was Howard’s destiny, and she encouraged him at every opportunity.

Niece Margaret Hodges McLain describes her Aunt Elizabeth as a perfect southern belle whose petite stature only made Uncle Howard seem that much larger. Mrs. McLain recalls the Hills visiting Ashville during breaks from movie work.

Niece Margaret Hodges McLain describes her Aunt Elizabeth as a perfect southern belle whose petite stature only made Uncle Howard seem that much larger. Mrs. McLain recalls the Hills visiting Ashville during breaks from movie work.

Howard often cooked meat entrees for family gatherings by the same method used on safari in Africa. He would dig a pit in the ground, build a big fire in it, then place meat wrapped in wet cheesecloth among the coals, cover it up, and let it cook all day, a process similar to Hawaii’s imu pits used at luaus.

While waiting for dinner, Howard would set up hay bales for targets, and demonstrated his many archery skills and trick shots. Margaret recalls seeing him shoot tossed dimes from the air, as well as helping the youngsters learn archery. Howard was well-respected in Elizabeth’s home town, where the local theater showed many of his films and short subjects.

Three years after their marriage, the Hills moved to Opa Locka, Florida, where Howard worked as a machinist at Hughes Tool Company, founded by the father of aviation pioneer Howard Hughes. While there, he read a book called The Witchery Of Archery, by Maurice Thompson, that inspired Howard to set forth on a path that would bring him worldwide fame and set new records, many of them unbroken to this day.

Howard made his first bow while working at Hughes. It wasn’t a very good one, but it signaled the start of a new career direction in archery. He continued making bows and arrows and working in the machine shop until 1932, when their California experience actually began.

Ekin relates that Howard was approached by famed newspaper editorial writer Arthur Brisbane, who wanted the Hills to move to his desert ranch near Barstow, California. Howard was to coach his sons in physical sports, while Elizabeth would tutor them in academics.

After Howard’s one-year contract ended on the Brisbane ranch, he went to Hollywood, intent on making a documentary film he had written, called The Last Wilderness. It emphasized hunting America’s big game rather than spending fortunes on jungle safaris.

The film was a quick success, made entirely outdoors without using a single studio set. Howard’s amazing archery skills were featured as he brought down every kind of large game animal in the American wild country. For the next year or so, he tirelessly promoted this movie by making personal appearances at each showing, dazzling his audiences during intermissions with incredible demonstrations of pinpoint accuracy.

Among Howard’s amazing feats were shooting dozens of arrows, rapid fire, into the exact center of a target from 45 feet, not only from a standing stance, but also lying on his back, side, belly, and from between his legs. His arrows often got damaged in these stunts because they were grouped so tightly there was scarcely room for them all in the target’s tiny center spot.

Howard also appealed physically to his audiences. At more than 6 feet tall, his muscular build and dashing good looks would have easily qualified him for leading roles in movies. He was immensely strong, able to pull any bow with ease. In fact, some of his bows were so powerful they took two men to string them unless he did it himself.

One of Howard’s first major records was a long arrow flight of more than 391 yards, set in 1928 using a bow with a draw weight of 172 pounds that he built for the feat. He could keep seven arrows in the air at one time, and split a falling arrow with another.

One of Howard’s first major records was a long arrow flight of more than 391 yards, set in 1928 using a bow with a draw weight of 172 pounds that he built for the feat. He could keep seven arrows in the air at one time, and split a falling arrow with another.

Some favorite stunts were shooting at small objects in midair such as coins, rings, wasps, etc, shooting cigarettes out of some brave soul’s mouth, rolling a barrel down a hill and firing an arrow into its bunghole, splitting narrow sticks with arrows, shooting birds from high in the air, striking a match with one arrow, then extinguishing it with the next, shooting two arrows at once to burst two separate balloons, ricocheting arrows off wooden boards to hit a target, and breaking several balloons consecutively that had been blown up inside each other.

When asked how he hit moving targets so easily, Howard replied, “You have to train your eye to look at a single spot. If it’s a man, you look at a shirt button; if it’s a Coca Cola sign, you look at the center of an O. You have to look at infinite spots.”

Ekin remarks that when Howard was “looking at a spot,” his eye would appear as if it were literally going to pop right out of its socket. One thing that caught your writer’s notice in Hill documentaries was the way he laughed and joked with bystanders, but the minute his bow came into full draw, a dead-serious look would suddenly appear on his face. As soon as the arrow was loosed, however, he immediately became jovial again. It’s like he was two different people.

Howard’s hunting skills were legendary. He killed more than 2,000 large-game animals with his bow, including a rogue bull elephant. Taught to hunt by a Seminole Indian, he could track any kind of creature, often dispatching it with one arrow from a distance that would have challenged a gun hunter. Elizabeth often accompanied him on safaris and other big game hunts.

But despite his predatory skills, the man was not without a sense of humor. According to Ekin, on one western hunting trip he fooled his comrades into thinking they were eating veal brought from home when it was actually a wild burro he had shot the previous day and cooked in his signature fire pit.

Another time, Howard slipped a fox into a huge kettle of rabbit stew. On yet another trip, Howard and his companions were perturbed by a fellow hunter’s thunderous snoring, which continued despite all attempts to gently waken him. Finally, Howard simply rolled him, sleeping bag and all, into an icy creek.

His skills and uncanny accuracy soon caught the eye of Hollywood producers in 1937, when Warner Brothers was shooting The Adventures of Robin Hood. This high-dollar movie starred Basil Rathbone and Errol Flynn (for our younger readers, Flynn was sort of like today’s Kevin Costner, but far more macho). Facing a select group of some 50 accomplished archers who tested for the movie’s arrow shots, Howard easily topped them all in accuracy.

According to Ekin, director William Keighley told Howard, “You’re hired. Tell the head property man what equipment you want and report Monday to teach 22 actors and six principals how to shoot.”

Howard made many shots with the camera looking over his shoulder from behind, substituting himself for an actor who had just been filmed from the front while pulling the same bow. He performed many dangerous precision shots, such as knocking a war club from Basil Rathbone’s hand and shooting at running spear throwers.

By his own estimate, Howard “killed” 11 men while shooting Robin Hood. Some were shot while on galloping horses, falling to the ground with an arrow sticking out of their backs or chests. In reality, his blunted arrows had imbedded themselves into a thick block of balsa wood backed up by a steel plate, worn under their tunics. Had Howard’s aim been off by just a few inches, it could have been fatal.

Actors complained that a powerful bow he used to insure accuracy packed such an impact force that they didn’t have to fake falling from their horses; he literally knocked them off. He did all the bow shots for Errol Flynn, as well as numerous Indian battle scenes for movies like They Died With Their Boots On, Buffalo Bill, and several other films involving archery.

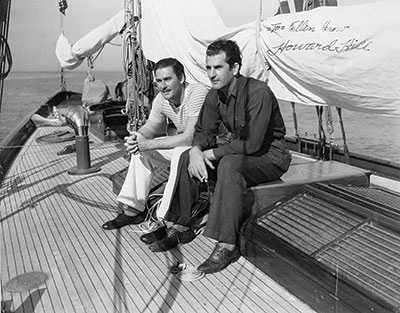

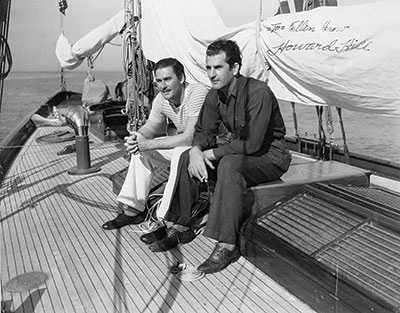

In a foreword to Howard’s book, Wild Adventure, Errol Flynn said, “When you meet Howard Hill you know darn well you’ve met him before, but you can’t remember where or when.“ The two became friends while on the Robin Hood set and spent many pleasant days afterward hunting, partying and fishing from Flynn’s yacht, the Sirocco, where he made one of the most incredible shots of his career.

He dropped a wooden barrel over the side, then threw the barrel’s cork after it. Quoting Ekin’s 1982 book: “While the boat and barrel were bobbing up and down on the waves, Howard proceeded to shoot the cork with an arrow that had a line attached to it. After retrieving the cork, he then shot the arrow again (with the cork still on the end of it), perfectly plugging the hole with the cork! This was made into a movie short, and can still be seen today.”

In 1940, Howard set up an archery shop in Hollywood, where he turned out some of the world’s finest bows and arrows. He made them for superstars like Gary Cooper, Roy Rogers, Iron Eyes Cody, Errol Flynn and Shirley Temple — complete with archery lessons.

By 1945, Howard had mostly given up on competitive shooting, since no one could beat him. In fact, he won 196 Field Archery tournaments in a row. His attention turned to hunting and exhibition work. He and Elizabeth built a fine, Southern-style colonial home in the middle of 10 acres in Pacoima, California, using marble imported from Sylacauga.

By the 1950s, Howard was making his own hunting movies, such as Tembo, released by RKO in 1952, which is still a film classic. In all, he produced 23 short subject films for Warner Brothers. He wrote several authoritative books on archery and big-game hunting, like Wild Adventure and Hunting The Hard Way, and has been featured in several other archery books.

In 1971, Howard was inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame. Birmingham sports editor Zipp Newman wrote, “Never has one man so completely dominated his sport as Howard Hill.”

His signature bows and arrows are still being manufactured and sold at Howard Hill Archery in Hamilton, Montana, operated by longtime friends Craig & Evie Ekin. For those interested in watching Howard’s demo films, Youtube offers more than a dozen, mostly filmed in the quaint, gender-patronizing style of the 1940-50s.

After an unparalleled lifetime of making bows, movies, and unbroken records, Howard and Elizabeth retired to a large, colonial style home they built in Vincent, which still stands today. Howard passed away in 1975 after a bout with cancer, and Elizabeth, always at his side, joined him in eternal peace less than a year later.

They now lie in repose in the Hodges’ family plot at the New Ashville Cemetery, just inside the fork of its service road. Their headstone is framed with two drawn bows, but nothing else at the site commemorates his world fame. Always the dedicated wife, Elizabeth’s marker does not show her birth date, only a final one, so as to not draw attention to the difference in their ages.

Margaret McLain describes Howard and Elizabeth’s life together as “a very long love story. She was his greatest fan.”

For a story on how Howard Hill touched the author’s life, read the print or digital version of Discover The Essence of St. Clair October & November 2014 edition.

Community pays tribute to ‘Peanut’ Bill Seales

Community pays tribute to ‘Peanut’ Bill Seales