A song to sing, a story to tell

Story by Linda Long

Photos by Susan Wall

Submitted photos

Terresa Horn was born to sing. No doubt about that on this Saturday night at the Dega Brewhouse in Talladega. The cowboy-booted, country music singing grandma belts out a rousing rendition of Ode to Billy Joe, a crowd favorite. Other requests come fast and furious, and Horn is happy to comply. She knows them all.

Horn stays busy singing at local clubs and special events in and around St. Clair County these days, but there was a time when her voice took her to the brink of the big time, a journey that started years ago from her from her home high atop Sand Mountain.

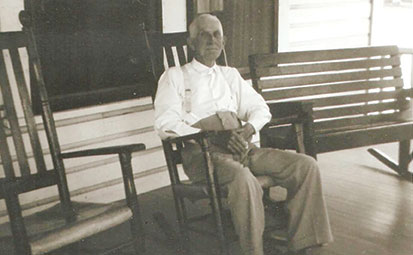

“I guess if there is any such thing as a music gene, I came by it honest,” she laughs. “My daddy could play just about anything there was – from the fiddle to the mandolin – and he had his own band. My brothers played bass and the drums and my mom? Well, she yodeled. Somebody was always making music at our house. It got pretty loud,” Horn recalled.

“People would ask my Mom how can you take this? She would just smile and say, ‘I know where my kids are.’ ”

One of Horn’s fondest memories growing up was Charlie B.’s Hootenanny, named for her father, Charlie B. Lang, and held every summer on a flatbed truck in her backyard.

One of Horn’s fondest memories growing up was Charlie B.’s Hootenanny, named for her father, Charlie B. Lang, and held every summer on a flatbed truck in her backyard.

“People came from all over the county,” said Horn. “It was an annual tradition.

Campers rolled in and stayed the whole weekend. My band would play and other musicians that we knew. We always had gospel quartets, and oh, my gosh, the food! Mom would cook dish pans full of chicken and dumplings and banana pudding. I remember one time daddy and them fried 300 pounds of catfish, not counting all the other food. Police officers would drop by and fix a plate, and politicians came to ask for votes. Everybody brought their lounge chairs and just had a real good time.”

As Horn recalls, her singing got its start in the family church. She was just four years old, but already familiar with gospel favorites. “I was nine when my Daddy put a microphone in my hand and got me up on stage for the first time,” she said. “We were at a square dance. I sang Silver Threads and Golden Needles, and I was hooked.”

That microphone was in her hand to stay. By the time she was 12, Horn and her brother had a weekly radio show. “It was live music, and we were on every Saturday morning,” she remembered. By the time she was 16, Horn was playing nightclubs from Birmingham to Atlanta. “I remember I even sang in one in Pell City back then.”

After a few years of life ‘on the road,’ Horn made her way to the mecca of country music, Nashville and historic Printer’s Alley, where country music stars are born. “Everything was going real good for me,” said Horn. “I did all the clubs along there (Printer’s Alley), including Tootsies. I sang with some really good people – Mickey Gilley, Marty Stuart. Tanya Tucker used to come by and sing with us, and I did one outdoor show that had some really big names. Willie Nelson played that one. I shared a tent with him, and that was pretty cool.”

Folks in Nashville began to sit up and take notice. As one promotional flier read, “Terresa Jhene (her stage name at the time), country gal, with super talent, debuts.” She signed a recording contract with C.B.F. Records and cut her first album, If This is Dreaming, which made the charts.

For Horn, it was “a dream come true…like a storybook. It just didn’t seem real. I went to the studio to cut a single, but when the producer heard me, he said, ‘Oh, no. This girl’s too good.’ He got the musicians in there, and we cut an album right there on the spot.”

In the meantime, another single, Sooner or Later, had climbed to number three on charts in Europe. “We were all set to do a European tour – radio shows, TV shows. They were all scheduled, and tour dates had been set.”

That’s when fate dealt a cruel blow with a phone call that put an abrupt halt to the tour and almost derailed her career. Her beloved Dad had suffered a heart attack and died a few days later.

“I came back home and thought I would just postpone the tour, but I kept putting it off,” said Horn, and just never went back. Instead, I stayed home to take care of my mother. I would do it over again because it was the right thing to do. My mom and dad were my biggest inspiration and my biggest fans. I don’t know. It seems like when my parents died, the music went out of me. It was a long time before I could sing again.”

“I came back home and thought I would just postpone the tour, but I kept putting it off,” said Horn, and just never went back. Instead, I stayed home to take care of my mother. I would do it over again because it was the right thing to do. My mom and dad were my biggest inspiration and my biggest fans. I don’t know. It seems like when my parents died, the music went out of me. It was a long time before I could sing again.”

Today, the music’s back. Horn says she is “really enjoying singing without all the pressures associated with the entertainment business. It was demanding, but I wouldn’t trade any of the memories. I did get to do a lot of fun things that other people don’t get to do. Still,” she said, somewhat wistfully, “you do look back, sometimes, and wonder what if, but I have no regrets.”

Horn sings with the Memories Band and as one half of the Just Two duo partnered with local entertainer Gary Blalock. When Horn isn’t singing, she can be found at her second career as secretary at Cropwell Small Animal Hospital.

These days, family means husband Bobby Horn and their blended family of four children and eight grandchildren. Their log cabin home by Logan Martin Lake sees a lot of music and a lot of parties – maybe not as big as Charlie B.’s Hootenanny, she said, but “we’re getting there.” l