Lonergan’s story, life’s work an inspiration

Story by Carol Pappas

Story by Carol Pappas

Photos by Wallace Bromberg Jr.

He has been described as “the boy who lived to draw.” Sitting in an easy chair at his home in Chula Vista, surrounded by a couple of Shelties, a black Lab and a lifetime of his works, John Lonergan pauses a moment and reflects. “If I had known in high school the level where I am now, I would have been impressed.”

But the inherent perfectionist in him quickly adds, “You never get to the level you want to be.”

With an impressive career as an art teacher to his credit — both in public school and in the private sector — gallery showings, commissioned work and his art hanging in private and corporate collections virtually around the world, one might be tempted to call it the pinnacle.

But add a book about his life and work, more shows and commissions up ahead, and it is easy to see that Lonergan isn’t done yet.

The latest triumph for the St. Clair County-born Lonergan, who was inspired by a teacher when he was growing up in the village shadow of Avondale Mills, is a book, John Longergan, The Painter. Published by Birmingham-based Red Camel Press, the book is a rare opportunity to see the world through an artist’s eyes.

It is dedicated to his parents, John L. Sr. and Jennie S. Lonergan, “who gave me confidence and support to follow my dream to become a painter;” his wife, Sandra, a gifted and noted photographer, who is “my best critic and treasured lifelong sweetheart;” and Doe, his black lab, “my life’s best friend.”

Through paintings and commentary, it deftly weaves the story of a young country boy from a small Southern town, who builds a life as a master painter and inspiring teacher. The gift his parents and teachers recognized early in his life is a gift he continues to give others through his painting and teaching.

His students call him the master. And it was one of those students who was so inspired by his teaching and his work that she suggested the book. She happened to be a book publisher, and three years later the collaborative effort evolved into: John Lonergan, The Painter.

When Liza Elliott first broached the idea of a book, Lonergan recalled it as an “interesting” proposition. “But I didn’t think much about it. When I found out she was serious, we went to work on it.”

They selected paintings and visited about 50 homes to photograph from private collections over the next three years. Still life, figures, landscapes and portraits are the sections of the book.

They, alone, could tell the story of a gifted painter who talks to us through his canvas. But there is something extra about this book, something personal that immediately draws you into it.

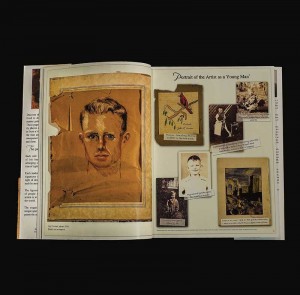

It is the self portrait, circa 1958, pastel on newsprint. The chiseled detail of the face, the light, the eyes gazing straight at you immediately capture you. And it is the photographs he includes under “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” that endear you to this life story through words, pictures and of course, the center of it all — the art.

There is a picture of his perfectly, hand drawn “Redbird” sitting on the branch of a tree. His canvas then was composition paper, now yellowed with age. Under the redbird drawing is the simplicity retold: “One of my favorite subjects in the second-grade.” Underneath is a photograph of him in the second-grade. In parentheses, he adds the moniker, “the Redbird artist.”

There is a picture of his perfectly, hand drawn “Redbird” sitting on the branch of a tree. His canvas then was composition paper, now yellowed with age. Under the redbird drawing is the simplicity retold: “One of my favorite subjects in the second-grade.” Underneath is a photograph of him in the second-grade. In parentheses, he adds the moniker, “the Redbird artist.”

The next few pages are peppered with photographs and drawings from his childhood and teen-age years, parenthetical humor enhancing each nostalgic look. The photograph of a toddler all dressed up in cowboy suit riding on a pony explains, “A photographer traveling with a pony shot this. (I wanted to be in a Roy Rogers and Dale Evans movie. It didn’t happen)

There are photographs of his parents, a drawing of a horse with calf “Matted and displayed by my 4th grade teacher, Mrs. Betty Cosper.” It was fitting that he included that particular photo. Teachers would have a great influence on his life, and he never fails to give them credit. He speaks of Mrs. Cosper in reverent terms. “She was a big influence. She really took an interest in my artwork.”

He includes a photo of his high school art teacher, Mrs. Dorothy Mays, noting that she “inspired me.” He talks of Iola Roberts, the principal at the old Avondale Mills School, who was a strict disciplinarian but gave her students an appreciation for the arts. “She had a real passion for Avondale Mills kids.”

In light of a perceived divide between “town” kids and mill village youngsters, she would tell them, “ ‘Remember, you are as good as anybody.’ You know, I didn’t know I wasn’t,” he said. “She would definitely get my vote for best educator in Pell City ever. O.D. Duran was good, too.” Perhaps that is why their names now don two of Pell City’s elementary schools.

After a brief career in commercial art, Lonergan, himself, would become art teacher at the same high school where Mrs. Mays mentored him. After he was hired, he expressed doubt to her that he could handle it. “I don’t know what I’m going to do,” he said he told her. “ ‘All you have to do is stay one day ahead of them,’ ” she replied. And that he did for the next 25 years.

Past the pages of Lonergan’s childhood comes present day, where he passes along his gift and his inspiration to others — The Atelier, the French term for workshop of a master painter and his students. It is this studio in Birmingham, where they have trained for more than two decades.

In her narrative of that particular section, Elliott writes, “For those who collect John Lonergan’s paintings, he is an inspiration. For those who study with John Lonergan, he is the master.”

For the section on Teaching, she describes it thusly: “That is the Lonergan method. Teach and inspire. They are better painters for it.”

In Still Life, she says, “Like a magician, with a paint brush as a wand, his paint strokes cast the spell, conjuring up gorgeous pictures that never cease to amaze.”

For Figures, “What matters to Lonergan is the light, the shapes, the colors of the people and the location around him. The challenge is to convey the emotion of the moment through a fully realized painting, giving voice to the people through the medium of oil paint.”

Portraits, as the other works, tell a story. “The faces project personality,” Elliott writes. “The settings provide context. Taken together, he reveals an episode in that person’s life, at that moment in time.”

His rural roots obviously influence Landscapes.

“John Lonergan shares his private world with us and we, too, can bask in the brilliant moments of nature’s beauty.”

And his love of animals is evident in the inclusion of the pictures of Molly and Doe, his Sheltie and Lab, on the final page with a note, “We show our love of God by our love for all people, friends, family, and of course, our pets. That’s all that counts.”

Although spoken years before Lonergan was born, a quote from Edgar Degas, the French artist believed to be among the founders of Impressionism, seems to capture the very essence of Lonergan. “Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.”

And through his life and his works, the eyes of the beholder see plenty.