Wayne Johnson strives to make a difference

Story by Elaine Hobson Miller

Photos by Wallace Bromberg Jr.

Wayne Johnson has thought a lot about his legacy and what he will leave behind when he has departed this earthly life. He wants it to be his work with veterans. Considering what he does for and with them every week, that shouldn’t be a problem.

Although he recently retired after five-and-a-half years as veterans outreach coordinator for the St. Clair County Extension office, Johnson still takes veterans to medical appointments, helps them access their government benefits and makes regular visits to the Col. Robert L. Howard State Veterans Home in Pell City. “I never considered it work because I enjoyed it so much,” he says of his time with the extension office.

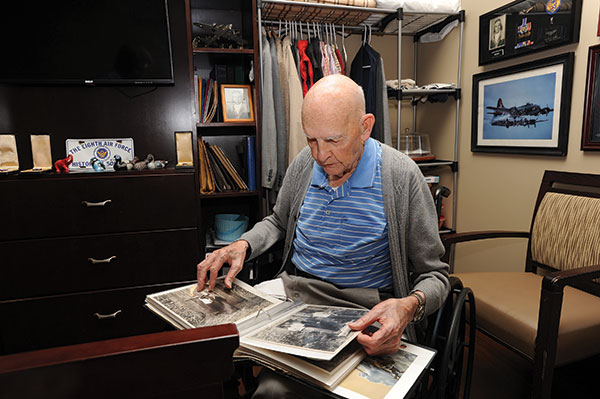

Johnson was one of the first people Frank Veal met after moving into the veterans home, and the pair have been friends ever since. A Korean War vet who served in the Air Force for 26 years, Veal is a native of Troy. He owns a van with a ramp that he lets Johnson use to ferry other vets to various appointments. The veterans home takes care of its residents’ medical trips.

“Wayne was here to help Frank celebrate his 91st birthday in August,” says Reshina Pratt, administrative support assistant at the veterans home. “They are very close.”

Johnson also is close to Veal’s next-door-neighbor, Tom Kelly, who is originally from Maryland but raised his family in Alabama. Another Korean War veteran, Kelly has been at the home since 2014. “Wayne visits us weekly, more if we have a need,” says Kelly. “Sometimes he brings us lunch, like barbecued ribs, and he has made trips to Montgomery with us.”

“He’s a good guy, and we appreciate him,” says Veal. “He’s a handy man to have around.”

It’s Personal

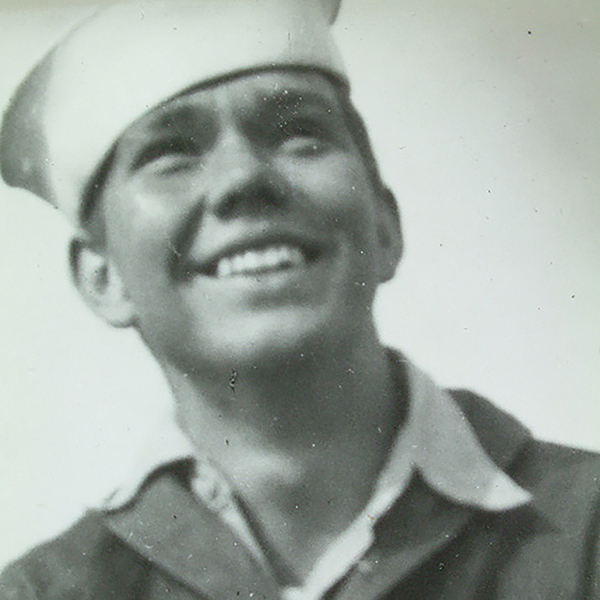

One of the reasons Johnson has such an affinity for veterans is that he’s a veteran himself. He grew up in Portsmouth, Va., and joined the Air Force right out of high school. He retired after serving for 20 years, then worked for a government contractor 14 years. Later, he was employed as activities director at the veterans home. He retired from his job with the Extension Service in April to help take care of his one-year-old grandson, Jaxson, and as of late August, ACES still had not found a replacement.

From the beginning, Johnson’s vision was to get out into the community to find veterans and widows of veterans who needed assistance, according to Lee Ann Clark, the St. Clair County Extension Service coordinator. “He worked hard and successfully accomplished his goal of making veterans aware of the benefits that are available to them and helped many obtain these benefits,” Clark says. “Not only did he reach the elderly and middle-aged veterans, but he also assisted younger ones.”

Although his retirement plans originally included relaxation, fishing and spending time with his grandson, he continues to be an asset to the veterans in the community in some capacity.

Johnson estimates that he probably takes vets to appointments and helps them run other errands three times a week. “Some live in their own homes but can’t get out and get their groceries by themselves,” Johnson says. That’s where Veal’s van comes in handy. “I let him keep it at his house,” Veal says.

Johnson met his wife, Cheryl, when both were in the military and stationed in Kansas. She spent 10 years in the Air Force in accounting. When he retired, they decided to come back to Pell City because it was her hometown. They have two daughters and three grandchildren. One daughter, Jaxson’s mother, lives in Pell City. The other daughter, who has two children, lives in the Netherlands, where Johnson was once stationed while in the Air Force.

“Wayne does an awesome job with local veterans,” says Cheryl Johnson, who has been married to Wayne for 30 years. “We need more people like him because there’s a huge need with veterans in this county. So many are here alone, with their children in different states. He works well with people, and he’s still helping with some he was attached to. He picks up people as needed for appointments for a few who still reach out to him, and Lee Ann still refers people to him from time to time. He tries to direct them to the right resources if he can’t help them.”

His motivation, she says, is that he just loves reaching out to veterans. “When the St. Clair Extension Office had that opening, they wanted a veteran, and he was in a position to take the job,” she says. “It was part time, and he took it to have something to do. Then it got bigger and bigger because there was so much need out there. A news article would post, and the calls would continue to come in.” Cheryl says her husband connects with people. “He loves war movies and the history of wars, and loves the stories the veterans tell him,” she says.

Prior to its recent COVID-19 lockdown, the Col. Robert L. Howard State Veterans Home saw Johnson drop by at least once a week to participate in activities with residents. “He’s a great resource for us,” says Reshina Pratt. “One day a homeless vet from out of town stopped by and we called Wayne, and he helped him get the assistance he needed. He’s a kind, caring, helpful man. Even though he has retired (from the county extension office), we still call on him for assistance. I know he’ll be back here after the restrictions are lifted.”

The Rev. Willie E. Crook met Johnson about 20 years ago when Crook was a contractor building community churches. Johnson helped get Rocky Zion Baptist Church in Pell City built, according to Crook.

“When I worked with him then, he had another job but came by and checked on the construction twice a day, before and after work,” says Crook.

“He’s a dedicated man. The Lord led me to build a ranch for underprivileged, inner-city kids. I talked to Wayne about helping me, and we started Gateway to Life Youth Ranch in Ohatchee 12 years ago. He’s president of the ranch, which hosts at-risk kids on weekends so they can enjoy the outdoors, fishing, woodworking and the animals at the ranch. We also mentor fourth- and fifth-grade boys’ classes at Saks Middle School in Anniston.”

Crook vouches for the fact that Johnson has befriended many veterans through the years. “Many times, he has come to the ranch to pick up or drop something, and he has had a vet with him,” Crook says. “He cares about them and would do anything in the world for them. He’s a giving man. We didn’t have any funds when we started that ranch, and he has gone into his pocket several times.”

A modest man, when asked why he continues to work with veterans, Johnson has a quick and simple reply: “It gives me a sense of satisfaction.”