At 99, memory of French Liberation still clear to World War II vet

Story by Scottie Vickery

Contributed Photos

As First Lieutenant William E. Massey plummeted 26,000 feet toward the ground, the 23-year-old bomber pilot realized he had reached the end. “This is my last mission,” he thought. “It’s all over.”

It was June 19, 1944, and Massey was flying his 19th mission in World War II when his B-17 Flying Fortress was shot down over Jauldes, a small village in France. Hurtling through the air, he worked frantically, managing to partially attach his parachute to his harness and pull the rip cord just in time.

After a miraculous landing, he spent more than two months with members of the French Underground, who helped hide him and other Allied soldiers and airmen from the Germans.

“We were on a mission that took 76 days,” Massey said, recounting his story just days before the 75th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris on August 24. “I like to tell my story. Most people think that war is just shooting at each other, but there’s a lot more behind a military life.”

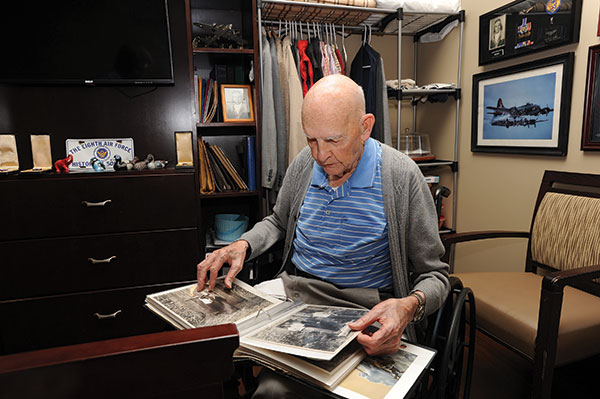

Massey, who will celebrate his 99th birthday in November, has lots of memorabilia decorating his room at the Col. Robert L. Howard State Veterans Home in Pell City. There’s a framed map of France – the one he carried the day he was shot down – and a large photo of a B-17 cockpit. A collection of awards dot the walls, as well, including a 2015 letter stating that he would be presented with the Legion of Honor, France’s highest order of merit.

He accepted the award in January 2016 on behalf of all the soldiers who volunteered their services during the war. “They say that 1 in 4 airmen didn’t make it back,” said Massey, who flew with the 401st Bombardment Group of the 8th Air Force out of England. “So many paid the ultimate price.”

Volunteering for service

Born in Bessemer, Massey was 21 when he enlisted shortly after the U.S. entered the war in 1941. He saw a poster for Aviation Cadet Training and knew that’s what he wanted to do. “I had never been in an airplane,” he said. “I’d never been off the ground. I had such a desire to fly, though, I knew I could do it.”

He had 240 hours of training before his first mission and eventually flew two separate missions on D-Day, the Allied invasion of Normandy. The fateful flight, which he wasn’t scheduled to make, came 13 days later. “One of the pilots showed up drunk, and his crew refused to fly with him,” Massey said. “They asked me if I wanted to just take his place or go with my own crew. We had flown 18 missions together, and I knew what each man was capable of doing, so I chose to take my own crew.”

They were headed for an airfield in Bordeaux. “Our intelligence had learned that the Germans had amassed large numbers of troops and equipment to combat the invasion. The mission was to destroy the airport and as much of the equipment as possible,” he said.

Thirty minutes from their target, they ran into anti-aircraft fire. The cockpit filled with smoke, and Massey knew the plane’s hydraulic system had been hit. “There was no chance in putting that fire out, so I immediately hit the bail out switch,” he said. “At an altitude of 26,000 feet, the temperature runs about 32 degrees below zero. I was trying to buckle my chute to my harness, but my hands were so cold, I couldn’t get them to function right.”

Finally, as the air grew warmer closer to ground, he managed to get the left buckle hooked with about 3,000 feet to spare. “The ground was coming fast,” he said, and he had to decide whether to keep trying to fully attach the chute or pull the rip cord with just one buckle attached.

“That’s what I did, and thankfully it opened clean and blossomed out,” he said. “The jolt was so strong it pulled my boots off. I hit the ground in my stocking feet.”

Massey knew he could see German soldiers at any time, so he hid himself and his parachute in the woods. He tried to catch the attention of a French farmer in a nearby pasture but was unsuccessful. A little later, another farmer came by and seemed to be searching for something. “I took a chance the old gent told him where the American airman was,” Massey said. “I summed that one up just right. He had a horse cart filled with hay. He hid me under it and off we go. Where, I didn’t know.”

Massey spent the night in a barn, hiding in the hayloft. The next day, the man brought two more members of Massey’s crew – 2nd Lt. Lewis Stelljes, a bombardier, and Sgt. Francis Berard, a waist gunner – who had also survived the crash. They later learned that the seven other members of the crew perished on the plane, a reality that still haunts Massey today.

A network of safety

The man who helped them was part of the French Underground, which maintained escape networks to protect Allied soldiers and airmen from the Germans. It was one effort of the French Resistance, which sabotaged roads and airfields and destroyed communications networks to thwart the enemy. It also provided intelligence reports to the Allies, which was vital to the success of D-Day.

“Their job was to be a nuisance,” Massey said. “They were going to look after us, and we were going to stay and fight with them. From then on out, we moved about quite frequently to different houses. We mostly slept in barns.”

Massey fondly remembers a 5-year-old girl who occasionally brought them food, which was getting scarce in France. “It was normally a piece of bread, cheese or a boiled egg, but Lord have mercy, it sure was good,” he said.

Eventually they met a man named Joe, who said he was a member of the Office of Strategic Services, a predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency. He promised to help them escape. “One night, a cargo plane came in with more ammunition and food,” Massey said. “When it took off to return to England, there were three happy Americans on board. We were on our way home.”

During a debriefing with an intelligence officer, Massey learned that paperwork supporting his promotion to captain had been sent in the same day his plane went down. When he asked about the status, the officer told him, “It will catch up with you.” The promotion never did, and it is one of Massey’s biggest regrets.

“I was presumed dead, and they didn’t promote dead men. I worked for years to get it straightened out,” he said, adding that records from the 8th Air Force were destroyed when the National Personnel Records Center in Missouri burned down in the 1970s. “Getting shot down changed my whole life, but I was happy to be able to do something for my country. My country has done so much for me.”

Massey returned home and attended the University of Alabama, where he earned an industrial engineering degree and met his wife. The couple raised two children and were married for 56 years before she passed away. Massey, who worked for General Motors for 31 years and retired in 1980, continued to fly with a Reserve unit for about six years.

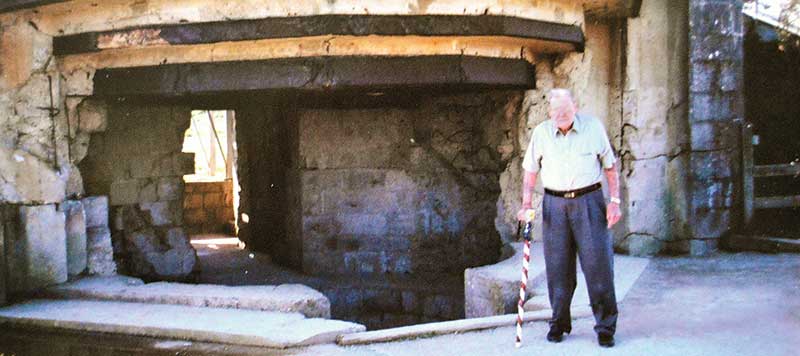

In 1961, Massey, Stelljes and Berard returned to France for the dedication of a monument honoring the crash survivors and the seven men who perished. While there, they visited with many of the people who helped them escape, even reconnecting with 21-year-old Jean Marie Blanchon, who had brought them food when she was 5. Shortly after the trip, Massey was quoted in The Birmingham News as saying, “We were there to thank them, but they were still thanking us for coming over to fight for their liberation.”

For years, Massey continued to correspond with the mayor of Jauldes, who wrote the following in an undated letter to the American airman:

Every year on the 8th of May (Victory in Europe Day) the population goes to the monument and after ringing bells to the dead, the mayor places a wreath and observes a moment of silence. Nobody here has forgotten the sacrifice of your compatriots.

Beatrice Muse Price:

Beatrice Muse Price: “Every time I turn around, I’m involved with something that’s made me think, ‘Can you imagine this?’ I’ve never seen any reason to stop with less than you were capable of doing. Now that I look back on it, I can’t remember anything I was afraid to do, and I think that’s why I had such great opportunities everywhere I went,” she said.

“Every time I turn around, I’m involved with something that’s made me think, ‘Can you imagine this?’ I’ve never seen any reason to stop with less than you were capable of doing. Now that I look back on it, I can’t remember anything I was afraid to do, and I think that’s why I had such great opportunities everywhere I went,” she said. Despite never having left Alabama, she boarded a train by herself and went to the Grady Memorial School of Nursing in Atlanta, graduating three years later in 1944 as a registered nurse.

Despite never having left Alabama, she boarded a train by herself and went to the Grady Memorial School of Nursing in Atlanta, graduating three years later in 1944 as a registered nurse.

Tales of survival from Omaha Beach

Tales of survival from Omaha Beach “Because the weather was so bad that week,” Hilman explains, (German Field Marshal) Rommel had left the area to attend his wife’s birthday party, thinking we couldn’t land with that kind of weather. The Germans needed aggressive field leadership, and with Rommel gone, they were left without.”

“Because the weather was so bad that week,” Hilman explains, (German Field Marshal) Rommel had left the area to attend his wife’s birthday party, thinking we couldn’t land with that kind of weather. The Germans needed aggressive field leadership, and with Rommel gone, they were left without.”

He spoke of his bombing mission to Berlin a month earlier – on May 7 and May 8. “On May 8, we turned around and went back to Berlin and bombed it again. You can’t imagine the devastation.”

He spoke of his bombing mission to Berlin a month earlier – on May 7 and May 8. “On May 8, we turned around and went back to Berlin and bombed it again. You can’t imagine the devastation.”