Ashville’s Mattie Lou Teague Crow

Story and photos by Jerry Smith

Story and photos by Jerry Smith

Submitted photos

Those of us who work with history sometimes stand on broad shoulders as we search for every pertinent detail, no matter how obscure, to ensure the veracity of our offerings.

Accurate, comprehensive input is as vital to us as a blueprint is to a construction foreman. Occasionally, we encounter a single book by an author who writes as if they were actually there. Such a work is History of St. Clair County, Alabama by Ashville’s Mattie Lou Teague Crow, the one go-to book for most beginning researchers.

While other writers such as Rubye Hall Edge Sisson (From Trout Creek To Ragland) and Vivian Buffington Qualls (History of Steele, Alabama) have expanded our knowledge of their communities, Mrs. Crow’s book is the single, definitive work that covers the whole county.

Writer and historian Joe Whitten fondly characterized his colleague as “… a Southern lady through and through, with an iron fist inside a velvet glove. When necessary, she would not hesitate to remove the glove.”

She’s reputed to have arranged a business meeting with a very important official from Montgomery. When he walked in the door of the restaurant and sat down, she immediately chastised him for not removing his hat in the presence of a lady.

Her penchant for history began in early childhood while living in her mother’s hotel and boarding house. In those days, Ashville was a bustling city with lots of opportunity for her to pester guests and travelers for every detail of their adventures and knowledge of the outside world.

Life at the Teague Hotel

Mattie Lou was born near Ashville in 1903, the same year the Wright Brothers first flew. She was the seventh and youngest child of Talulah (Nunneley) and John Rowan Teague. Her father, a farmer, died when she was only 2.

Quoting an entry in Heritage of St. Clair County by Mary McClendon Fouts, “… Lula Teague could not support her family on the farm, so she moved to Ashville and took in sewing for a time.

“There was a large two-storied house built by Curtiss Grubb Beason, about the time that Ashville was incorporated, where the Union State Bank stands today. Lula Teague’s brother, Robert Nunneley, and his wife Emma had operated it (as the Village Inn) for many years.

“Robert decided to retire, and Lula then operated it until her death in 1942. Her daughter, Annie, operated it for 10 or more years after that. This … is where their seven children grew up. It was a sad day in 1960 when the old hotel was demolished.”

Also in Heritage, Mattie Lou’s sister, Annie (Teague) McClendon recalls: “I remember how our mother bought this old house in the year of 1909 and moved us there: Grandmother Nunneley, Uncle Rufus, my four brothers, my little sister (Mattie Lou) and myself.

“After she made a small down payment on the place, we had no money, so we all worked, helping as best we could. The boys helped, not only with the chores, but at any little job they could find, in order to buy their clothes and shoes and help with the expenses. I stopped school to help with the housework. Our baby sister did her part, too.

“I remember the big kitchen and dining room where so much food was prepared and served.” Mattie Lou’s daughter, Ellen (Crow) Smith, adds that a lot of that food came from the family garden, chicken coop and smokehouse. She also says her mother’s job was ironing linen napkins for the dinner table, a job she hated and prophetically swore that when she grew up she would invent paper napkins that could be used once then thrown away.

Annie continues, “We had a black mammy whom we loved very much. She was Josephine Smith, often called Mammy Jo. She was with us about 30 years.

“I remember how Mama got up long before daylight and worked long after dark. I remember the cheerful living room with open fire and piano, where we all gathered to sing. Our mother loved this part of the day most.

“I remember the big front room where the ‘drummers’ slept and where they showed their samples on tables or wooden planks laid across the foots of beds. I remember the doctors and their families who lived in this house and called it home, … and the teachers who boarded here (during school terms).

“I remember when our little sister (Mattie Lou) went away to school … and how we looked forward to Christmas and Thanksgiving, when she would be home.”

An obsessively inquisitive young Mattie Lou found a gold mine of knowledge among guests who lived at the hotel, many of whom were much educated and experienced in life.

In a 1999 News-Aegis story, Joe Whitten writes, “Born when this county was still in swaddling clothes, Mattie Lou lived in St Clair County for nearly a hundred years. As a girl and young woman, she heard Civil War battle stories from the old veterans themselves.

“She learned of Reconstruction hardships from the men and women who lived in Ashville in those days. It is no mystery why history was a life-long passion with her.”

Every one Mattie Lou met knew things that she yearned to discover and understand. She often eavesdropped to hear uncensored war stories as old soldiers chatted on the front porch after supper.

As a child, she loved to sneak into courtrooms during trials, sitting in the back row to avoid attention, but the judge would order his bailiff to remove her and her friends when a particularly heinous matter was before the bench,

She diligently collected and annotated an unrivaled historical database. It’s said that her hope chest was full of historical documents instead of linens and personal items. In a sense, she was the history Wikipedia of her day.

Mattie Lou becomes Mrs. Crow

Ellen tells that her future father, 25-year-old Abner (Ab) Hodges Crow, spent much of his leisure time at a wooden bench on the town square, chatting with his buddies as young men are wont to do. Naturally, this talk often included the opposite sex, which probably hasn’t changed since the days of the Pyramids.

Mattie Lou, some 11 years younger than Ab, sometimes walked by with a group of friends. He had his own way of expressing admiration and, once the girls were out of earshot, was known to say, “One day I’m going to be compelled to marry that girl.”

Ab was not known for being straitlaced and, given the age difference, her mother was not really fond of them getting married. Mattie Lou said in a Birmingham News story, “Momma told the man I married that I had to have at least two years of college education before I could settle down.”

Like any obedient but strong-minded young woman of that post-Victorian era, Mattie Lou accepted this condition, and immediately after graduating high school in 1921, she went to Alabama College for Women, which is now the University of Montevallo. She and Ab were married a few years later.

He’d learned a little about the pharmacy business while working for Dewberry Drugs in Birmingham and established a drugstore on the square in Ashville. Ab had no formal teaching in drugs, so had to employ a full-time pharmacist.

In 1932, the local sheriff was killed in action. Ab was appointed by the governor to complete the late sheriff’s term and was re-elected, serving a total of about eight years. Ellen recalls going with her father to homes out in the countryside, to inform families of the loss of one of their own. These trips were part of the sheriff’s duties, since there were no telephones.

Ellen said they usually went after her father had closed the drugstore for the day and, with no rural electricity, most of these grim visits were in pitch dark, where they often encountered snarling dogs in the middle of the night.

She adds that her father was a compassionate man who never turned away a hobo or transient during the Depression. They were not allowed in the house, but Mattie Lou would tell them to wait on the front steps of the Methodist church, and Sheriff Ab would allow them to eat and sleep in the jail overnight.

Heritage hoarder

A well-educated woman, Mattie Lou also attended Jacksonville State Teachers’ College and University of Alabama, with degrees in elementary and secondary education and library science. Teaching was in her genes. Her grandfather, E.B. Teague, was a superintendent of education. Her father was principal of Springville School.

One of her first official assignments was a school for farmers’ and migrant workers’ children on Chandler Mountain. Rather than commute every day, she stayed in the homes of farm families and shared their lifestyle.

Mattie Lou taught at several St. Clair and Jefferson County schools, directed libraries at Judson College, Samford University and Homewood High School, and taught library science at night at UAB. But all the while she was stockpiling documents and information that would fuel her true avocation, preserving heritage.

By the early 1960s she had published a short history of Ashville Baptist Church, followed in 1973 by her most important single work, The History of St. Clair County, Alabama, the first book of its kind for our county. It endures to this day as a superbly written, comprehensive resource for all who would follow her lead.

Four years later, she produced Diary of a Confederate Soldier—John Washington Inzer 1834-1928, which edited and preserved the Civil War memoirs of one of Ashville’s premier citizens. It’s a treasure for Civil War buffs, as it factually portrays lesser-known factors, events and emotions as written by a highly literate man who served in a losing battle, then became a working part of Alabama’s re-entry into the United States after Appomattox.

Joe Whitten adds, “Perhaps her crowning achievement was the Ashville Museum and Archives. Dedicated in 1989, the Archive was originally in a room at the Ashville Library. Mrs. Crow believed it was important for us to know who we are and where we came from.

“She once commented, ‘Give me a name and I can take it back six generations.’ After listening to her recount names, dates and places, some of us wondered if she couldn’t take one or two families all the way back to Adam and Eve!”

Joe affirms that recently-retired archivist Charlene Simpson has virtually equaled her mentor’s level of expertise in ancestral name-dropping. Both will be sorely missed.

Every public document, official record, land deed, obsolete file, minutes of meetings, every scrap of yesteryear was sacred to Mattie Lou. She prevented several hundred pounds of courthouse documents from being burned, as evidenced by charred edges on some which were snatched from a roaring bonfire by Mattie Lou herself.

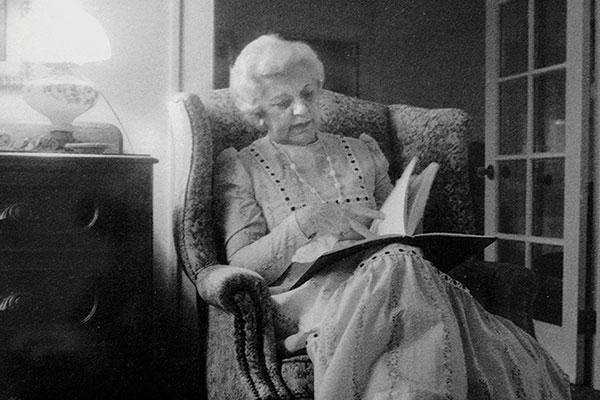

In a Birmingham News story by Melanie Jones, Mrs. Crow is quoted in her later years, “Why I’m just an old country lady that does as she pleases. My husband died 30 years ago and my children were both at the university. I sold the drug store and went back to school. I had a feeling Ashville would be very drab if I sat still.”

According to another News writer, Mike Easterling, Mattie Lou got an elementary education degree from Jacksonville State Teachers College (now Jacksonville State University) in 1949, then got a secondary degree in 1950, not long after Ab’s death. She later joined her children, Ellen and Pete, at the University of Alabama, getting a master’s degree in library science.

And she was true to her word about not sitting still. She managed, delegated, arm-twisted, conspired and charmed her way through a bewildering list of historical quests and civil projects, most of which would not have succeeded without her dynamic spirit.

In the same News story, she is quoted, “You don’t get to my age unless you stir up some trouble now and then. I’ve fought with some folks like a tiger to get something done. But it gets done, and then we’re friends. You just gotta shake ‘em up a bit.”

Relocating history

While some strive to move mountains, Mrs. Crow was content to move a huge, historic, 132-year-old, two-story building across town to save it from the wrecking ball. It had been moved before to a location beside the Ashville City Jail, but once again was in the way of progress.

A lover of all things historic, she could not bear to see this fine old structure demolished. Reluctant to put themselves at odds with the indomitable Mrs. Crow, the County Commission agreed that she could have the old building provided she moved it somewhere else, and soon.

A lover of all things historic, she could not bear to see this fine old structure demolished. Reluctant to put themselves at odds with the indomitable Mrs. Crow, the County Commission agreed that she could have the old building provided she moved it somewhere else, and soon.

Her crusade resulted in a new action group called Save The Ashville Masonic Lodge Council. In a mighty effort that’s still legendary among Ashville natives, Mrs. Crow spearheaded an effort to raise some $12,000 to cover expenses.

It took only two months to secure these funds as well as a nearby piece of property donated by Jack Inzer in memory of his grandfathers, both of whom were Masons and lay at rest in nearby City Cemetery.

It’s been said there was no door upon which she would not knock, no favor left uncalled, no politician immune to her bullyragging until the job was done and, with Mrs. Crow in the catbird seat, the 132-year-old Masonic Lodge soon found itself being moved to a third location.

The Masonic Lodge has been placed on the prestigious Alabama Register of Landmarks and Heritage. It now sits peacefully about a block from Ashville’s town square, serving as a monument to Ashville’s history and to its matron saint.

The Mattie Lou Teague Crow Museum upstairs contains many of her mementos. It’s presently open only by appointment. Call Ashville Archives for more information if you wish to visit. It’s a nice place to savor genuine antiquity.

In a 1990 Birmingham News story by Elma Bell, Council Member Hope Burger said, “As a result of Mattie Lou’s hysterics, all this is taking place. … This whole thing has been a team effort.”

Such was the stuff of which St. Clair’s own Steel Magnolia was made.

A ‘legendarian’ passes

Some years before retirement, the widowed Mattie Lou and her sister-in-law, Gladys Teague, operated a small antiques shop in a little gingerbread-trimmed white house beside Roses & Lace Bed & Breakfast. It was the former Ashville Academy, so she named it Academy Antiques.

She spent several of her last years quietly reminiscing about her prodigious life in a book-lined apartment adjacent to daughter Ellen’s former home in Irondale. Mattie Lou donated most of her vast collections to be shared by one and all at Ashville Archives.

She delighted in telling ghost stories to groups of children at Irondale Library. A 1982 Birmingham News article by Garland Reeves relates that one of her favorites was the sad saga of Old Tawassee, an Indian who stayed behind after his brothers were expelled from Alabama on the Trail of Tears.

Tawassee was hanged for civil mischief and is reputed to have haunted the town on that same day every year afterward by making his skeleton rattle in a local doctor’s closet and shaking the limb from which he was hanged.

Joe Whitten wrote in the News-Aegis, “On the day the archives was dedicated, she said ‘I haven’t done anything. I’ve twisted a few arms to get stuff done, but it was others who did all the work.’ But it was her love for a county and a place called home that inspired her.”

In the same article, Joe eulogizes his friend and colleague, “On a sun-washed, blue-sky day last week, Mattie Lou Teague Crow was brought back to the county and the town she loved, and was laid to rest in Ashville Cemetery.

“It was a fitting day to say farewell to a lady who left us an impressive legacy of books, biographical sketches and human interest articles about St. Clair County.

“She’s found a new place to call home now. I wonder if she’s taking notes for her next book?”

In Tuscaloosa, he pitched the idea for The Crooners to then program director Roger Duvall. “I loved Sinatra and the crooners, of course, and fortunately, he went for it,” Owen recalled.

In Tuscaloosa, he pitched the idea for The Crooners to then program director Roger Duvall. “I loved Sinatra and the crooners, of course, and fortunately, he went for it,” Owen recalled.

Story and photos by Jerry Smith

Story and photos by Jerry Smith A lover of all things historic, she could not bear to see this fine old structure demolished. Reluctant to put themselves at odds with the indomitable Mrs. Crow, the County Commission agreed that she could have the old building provided she moved it somewhere else, and soon.

A lover of all things historic, she could not bear to see this fine old structure demolished. Reluctant to put themselves at odds with the indomitable Mrs. Crow, the County Commission agreed that she could have the old building provided she moved it somewhere else, and soon.

Preparing for politics

Preparing for politics