Pell Citian a part of history in Iwo Jima

Story by Jim Smothers

Photos by Jim Smothers

and Michael Callahan

Contributed photos

You’ve probably seen the famous photo of the five Marines and a Navy corpsman raising the flag on Iwo Jima’s Mount Suribachi. It’s one of the most famous photos ever taken, and is a reminder of some of the deadliest fighting in any battle ever fought.

You’ve probably seen the famous photo of the five Marines and a Navy corpsman raising the flag on Iwo Jima’s Mount Suribachi. It’s one of the most famous photos ever taken, and is a reminder of some of the deadliest fighting in any battle ever fought.

Retired Sgt. Major George Boutwell of Pell City knows the photo well, but before he saw the picture, he saw the flag in person from his ship. That happened on the fourth day of the battle, the day he left his naval transport ship to help establish the Marines Fifth Division Medical Battalion’s hospital on the island.

Boutwell returned to the island earlier this year as part of the 70th anniversary of the battle. It’s not an easy place to get to, and no civilians live there today. It’s an isolated Japanese military outpost with few amenities and few visitors. But veterans and family members of both nations have been having annual observances there for the last 30 years. A monument on the beach was erected in 1985, written in Japanese on one side and English on the other. “On the 40th anniversary of the battle of Iwo Jima, American and Japanese veterans met again on these same sands, this time in peace and friendship. We commemorate our comrades, living and dead, who fought here with bravery and honor, and we pray together that our sacrifices on Iwo Jima will always be remembered and never be repeated.”

The order of the day was, “We met once as enemies, now as friends.”

Boutwell said he made the return trip thanks to the non-profit organization The Greatest Generation Foundation. Since 2004, the group has offered the opportunity for war veterans to return to their battlefields at no cost to them. The TGGF programs back to the battlefields are often emotional, but provide veterans a measure of closure from their war experiences, the chance to share in the gratitude for their service, and a venue to educate others.

Boutwell had returned to the island once before, in 1970, when he was stationed in Okinawa. The commanding general of his Marines division at that time authorized all personnel who had been there in 1945 to fly in for a one-day visit. There was a very small group there then, nothing like what he experienced this time.

In addition to his TGGF group of about 25 veterans, other groups also made the trip. The Japanese Cabinet came to this year’s observance for the first time.

Vehicles took visitors to the top of Suribachi to see monuments erected there, and for ceremonies marking the occasion.

Vehicles took visitors to the top of Suribachi to see monuments erected there, and for ceremonies marking the occasion.

This was quite unlike his previous two visits to the eight square mile island.

Reflecting back on the invasion of the island, Boutwell said he was ready to get off of the transport ship, which had been home for more than two months. While in Hawaii, his group had practiced beach landings, but it wasn’t until they went to sea that they were told where they were going. He was ready.

“Back then, I was nothing but a 20-year-old kid that was just like all the military personnel in the service now, 18-19-20-year-old kids. They know that nothing is ever going to happen to them,” he said. “And that’s what makes a good military force – you’ve got kids like that who think nothing’s ever going to happen to them.

“I could see the shore, and boats and amtraks (amphibious tracked personnel carriers) that had been destroyed, and some of them floating out there because the Japanese had hit some of them. We knew there are people who had been wounded and killed on the island there,” he said. “We had heard that John Basilone, who had won the Medal of Honor at Guadalcanal in 1942, had been killed on the first day.”

Basilone had been sent back home as a hero after Guadalcanal to help raise money for bonds, but after a few months wanted to get back into action.

When Boutwell went to the island on a landing craft mechanized (LCM), he drove a Jeep with a trailer off of a ramp where he found himself sitting still with all four wheels on the Jeep spinning in the volcanic ash.

Tractors pulled vehicles onto metal strips put into place by engineers to create a drivable road.

His battalion moved to the other side of the island to help set up the hospital where he subsequently served as a guard. He recalled an incident when an unarmed Japanese soldier walked down a dirt road into their area smoking a cigarette. He was quickly taken prisoner and held for questioning.

Boutwell saw some of the tunnels on the island, which were part of an elaborate defense system designed to help the Japanese fight against an expected invasion. Three days of shelling that took place before the Marines went on shore did some damage to Japanese defenses, but still the Marines took heavy casualties. Most of the 21,000 Japanese troops fought to the death or took their own lives during the battle. The American force of 60,000 Marines and a few thousand Navy Seabees on the island suffered 26,000 casualties, including 6,800 dead in the 36 days of fighting.

Boutwell saw some of the tunnels on the island, which were part of an elaborate defense system designed to help the Japanese fight against an expected invasion. Three days of shelling that took place before the Marines went on shore did some damage to Japanese defenses, but still the Marines took heavy casualties. Most of the 21,000 Japanese troops fought to the death or took their own lives during the battle. The American force of 60,000 Marines and a few thousand Navy Seabees on the island suffered 26,000 casualties, including 6,800 dead in the 36 days of fighting.

Boutwell was unaware if there were any surviving Japanese soldiers from the battle at the ceremony, but the widow of one of the soldiers sent him a gift of “peace beads.” At age 97, she makes the gifts to American veterans every year at the memorial ceremonies.

Boutwell said Iwo Jima was important because of its impact on the air war. Japanese forces there were detecting U.S. bombers flying from Guam to Japan. They in turned alerted Japan, and fighters were scrambled to meet the bombers before they arrived. Iwo Jima was also needed as an emergency landing area for aircraft returning from Japan that had either been damaged on the mission or had other problems.

While the focal point of the trip was the visit to Iwo Jima, most of his time was spent on other islands. Guam was home base. Boutwell was taken by surprise by the public outpouring of appreciation by the people of Guam toward the veterans for freeing them or their ancestors from Japanese oppression during the war.

While the focal point of the trip was the visit to Iwo Jima, most of his time was spent on other islands. Guam was home base. Boutwell was taken by surprise by the public outpouring of appreciation by the people of Guam toward the veterans for freeing them or their ancestors from Japanese oppression during the war.

His group also stayed on Saipan, and traveled from there the short distance to Tinian. There, they saw where the atomic bombs that ended the war were stored and loaded, and the runway from which the Enola Gay took off to make its historic flight.

Boutwell and his family have enjoyed attending service reunions in different cities over the years. He served in the Marines for 28 years, including time during the Korean Conflict and service in Vietnam.

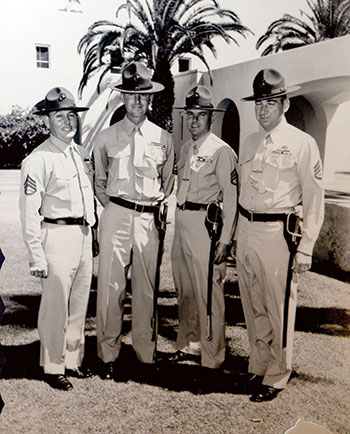

He also served as a drill sergeant at Camp Pendleton near San Diego, a job he said was probably the toughest in the Marines as far as the hours and intensity involved.

These days, he is an avid golfer, with a goal of walking 18 holes two or three times per week.

For more on our Special Veterans Coverage, pick up a print version of this month’s Discover The Essence of St. Clair or read the magazine in digital format online.