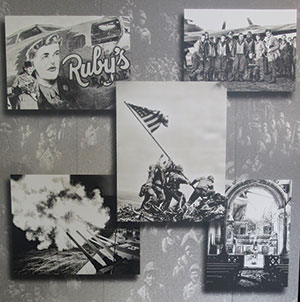

Epic tales from the men and women who went to war

Story by Carol Pappas

Photos by Graham Hadley

Contributed Photos

It may be cliché, but if the walls of the Col. Robert L. Howard State Veterans Home could talk, my, oh my, the stories they could tell.

But short of talking walls and such, Discover writers and photographers visited the veterans home just weeks before its fifth anniversary in Pell City to record those stories. The 254-veteran capacity home is full now, and stories abound from different wars, different perspectives and different walks of life. The common thread of this band of brothers and sisters is service to country first.

But short of talking walls and such, Discover writers and photographers visited the veterans home just weeks before its fifth anniversary in Pell City to record those stories. The 254-veteran capacity home is full now, and stories abound from different wars, different perspectives and different walks of life. The common thread of this band of brothers and sisters is service to country first.

These are real veterans, and these are their stories.

World War II seaman

went to ‘save the country’

Leo “Cotton” Crawford was only 17 when he boarded the USS Storm King as a seaman in World War II. He was 19 when he came home.

While today’s teens might lean more toward cars, careers or college, Crawford enlisted – like his two brothers – to, as he put it, “keep the Japanese from whooping us and take care of our country.”

Before he reached the age of 20, he knew all he needed to know: “We went to save our country, and we did.”

Crawford served in the Philippines. His two brothers – Herbie and Harold – had joined the Navy as well. “All three of us came out alive,” Crawford said, a hint of pride showing in his wide grin.

He doesn’t talk much about the war. Soldiers and sailors of his time rarely do. “We were in war,” he said. “It was expected” that you would serve. “They will take you if you’re a young kid ready to go. They took me. I enjoyed my time.”

When he returned home to Alabama, he was hired by the telephone company and stayed there until retirement as a cable repairman. “Ma Bell hired all of us,” he said of him and his brothers.

Now living at the Col. Robert L. Howard State Veterans Home, he dons his USS Storm King cap most of the time, covering up the locks of grey he has rightly earned. It’s not quite clear how he got the nickname, Cotton.

It could have been the blondeness of his hair as a youngster or that he was partial to picking cotton at the farm of his “kinfolks” in Cullman, he said. They would see him coming and say, “ ‘Here comes ole Cotton,’ and it stuck with me.”

Teen joins Navy,

stays for career

It would be 25 years before Bill Waldon would leave the US Navy after bidding farewell to his native home near Carbon Hill. The son of a miner, he left the service as an officer. “I’ve been around the world twice,” he said.

He married at 17, and he remembers his brother-in-law coming home on leave from World War II. Inquisitive, he asked him what it was like to serve. The brother-in-law put it this way: “ ‘The Army is doing the fighting. The Navy is getting the pay. And the Marines are getting the credit.’ So, when I joined, I wanted to fight in the Navy. We were old country boys. We got the best deal we could.”

He worked in the communications section aboard the aircraft carrier, USS Valley Forge. “I was very fortunate. I didn’t hear a bullet.”

Later, as he rose through the ranks, he began to give the orders. “If they were shot at, I’d tell them what to do,” he mused. “If they’re shooting at the ship, stay pretty close together.”

He talked of his own good fortunes taking orders through the years. “I had good people telling me what to do.”

World War II vet

dodges bullets as messenger

“They called me a messenger,” said Dyer Honeycutt, who served in the US Army in World War II in France and Belgium. “I called myself a runner.”

It was his job to get messages from one camp to another. So, run he did. “Bullets sounded like a whip, a pop” as they raced past him.

“I was shot at a lot of times,” but he was never struck. “I’d get about the length of a football field, and they started shooting at me. I had a lot of good buddies get killed. I still believe the Lord above was taking care of me.”

He was the son of farmers in Attalla and joined the service after high school. His method of carrying messages without getting hurt? “I’d go one time to the left and two times to the right. Then I’m hitting the deck. They’re shooting at me.”

He was the son of farmers in Attalla and joined the service after high school. His method of carrying messages without getting hurt? “I’d go one time to the left and two times to the right. Then I’m hitting the deck. They’re shooting at me.”

The dominant thought throughout was, “If the Lord wanted me to die, I would. If He didn’t, I wouldn’t.”

D-Day an ‘awesome’ experience

For James Majors, D-Day, the invasion of Normandy, could only be described as “awesome.”

From his vantage point on a troop carrier ship, “the sky was like a swarm of blackbirds. It was full of everything that could fly.”

His ship was on the first wave. Rockets were shot onto the beach. “The ocean behind me was full of ships. The sky was black with airplanes.” There was a church on top of the cliffs being used as a lookout by the enemy. “Our job was to knock it out, which we did.”

Ahead, he could see the cliffs up from the beach. Germans stood at the top shooting down at American soldiers as they climbed. “They were shot down, but our boys kept going. It was heartbreaking. They just kept going. I still have bad thoughts.”

After the initial invasion, it was Majors’ job to be a diver and clear the entanglements of barbed wire and wood the enemy had left to block the beach. “We cleared pathways for the big ships to come in.”

Majors was a motor machinist mate, running the diesel engines – “everything mechanical on the ship except the refrigeration.” It was the farthest away from his Gadsden home he had ever been.

He jokes about his trip from England to Normandy, which could be measured in the space of 48 hours. “I aged a year,” he mused. “I was 19 when I left England, and I was 20 when I got to Normandy. His birthday was June 4, 1945. D-Day was June 6. “I don’t know how many Germans we took out, but we dug a lot of foxholes,” he said. “If there is anything that will break your heart, it is remembering what went on that day.”

At the same time, Majors says he has “a sense of pride I was able to be part of the crew. We carried the mission out with pride. I would go back again if it was under the same circumstances. I would not go back in the mess our boys are in now. In Normandy and Southern France, we knew who the enemy was. They don’t know who our friends are.”

He has talked to his younger counterparts at the veterans home. “The people they’re training are killing the trainers.”

But as for his own experience that fateful day in June 1945, “I was proud to have served in the greatest battle ever fought, and I was right out front. That was something.”

For more stories about our veterans, the Veterans Home and the community that supports them, read this month’s edition of Discover The Essence of St. Clair either in the digital edition or in print.