Tales of a Springville inventor, entrepreneur

Tales of a Springville inventor, entrepreneur

Story by Leigh Pritchett

Photos by Wallace Bromberg Jr.

Submitted photos courtesy Carol Waid

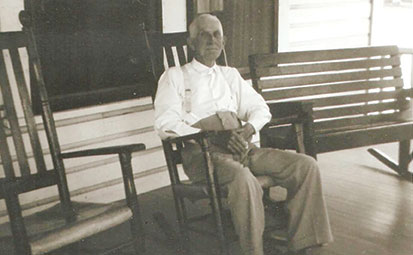

Marcus H. Pearson was a small, quiet, humble man, with big ideas that made an impact on farmers, herdsmen and churchgoers.

Those big ideas netted two patents (one when he was just 26), made putting up wire fences a little easier and aided congregations with their building projects.

Oh … and his chicken house once held Auburn University’s live War Eagle mascot.

According to granddaughter Carol Pearson Waid of Springville, Pearson was quite the entrepreneur. “Granddaddy had several different businesses.” Among them were Pearson Lumber Co. and Sawmill, a grocery store and a gristmill.

All were on property situated at US 11 and Cross Street. Also on the site were Pearson’s home, workshop that was full of punches and patterns, and, of course, the famous chicken house.

“All of this was Pearson property,” Mrs. Waid said about the expanse that surrounds Pearson’s home, where she and husband Frank Waid now live. “This is the house Grandma and Granddaddy built.”

The 1931 home features original wood floors and cabinetry, four fireplaces, a telephone directory from 1956, Pearson’s accordion and a bed that belonged to his grandmother.

The yellow building at the corner of US 11 and Cross Street that currently houses Louise’s Style Shop and C.E. Floral Gifts and Novelties was the grocery store.

Mrs. Waid worked at the grocery store as a girl. “I worked there for a nickel a day,” she said.

The lumberyard was behind Pearson’s house, as is the current home of grandson Tommy Burttram.

As for the gristmill, Burttram’s parents – Ed and Willie Pearl Pearson Burttram – remodeled it for their home as newlyweds. When they decided to build another dwelling, they relocated the gristmill and incorporated it into the architecture.

Being enterprising seemed to be a family trait as Pearson’s father, W.R. Pearson, was also a business owner. He operated a blacksmith shop just across US 11 from where the Waids live. Working in the blacksmith shop, Marcus Pearson learned smithing, buggy repairing and woodworking.

Kathy Burttram, Tommy’s wife, has a ledger from the blacksmith shop chronicling the work done there daily.

Close to the blacksmith shop was the home of Pearson’s parents. They had the first telephone, first radio and first bathtub in Springville. Mrs. Waid said neighbors came to see the bathtub with their towels in hand.

Born in 1879, Marcus Pearson received from his mother, Frances Amelia Truss Pearson, the lineage of the Truss family for whom Trussville is named, Mrs. Waid said.

As a child, Pearson watched the creation of what became a tourist attraction in Springville until the 1960s. Mrs. Waid explained that Springville gets its name from a spring, which later was transformed into a lake. “Granddaddy saw them dig (the lake) with oxen,” she said.

In 1909, Marcus Pearson’s red, Pope-Hartford Model B became the first automobile recorded in Springville. His was only the fourth vehicle to be registered in all of St. Clair County.

He married at age 41, played the accordion and harmonica, and did not believe in working on Sunday.

“He thought Sunday ought to be kept holy,” Mrs. Burttram said.

He was a disciplinarian, lived 95 years and enjoyed hearing Mrs. Waid play What a Friend We Have in Jesus on piano.

“Granddaddy was on the building committee of the ‘Rock School,’” Mrs. Waid said, referring to Springville’s historic hillside school constructed of rocks. “He wanted to build it on the level ground. But he was outvoted because people wanted it built on the hill so people from the train could see it.”

Mrs. Waid said one of Pearson’s friends was James Alexander Bryan, who was a noted minister and humanitarian in Birmingham. In fact, “Brother Bryan,” as he was called, officiated when Pearson married Opal Jones.

The Pearsons had three children, one of whom was Marcus M. Pearson. Son Marcus — Mrs. Waid’s father — assumed the lumber business in 1950, served on the board of education and was mayor of Springville in the 1960s, Mrs. Waid said.

When another son, Frank, decided to play baseball for Springville, the automobile that father Marcus H. Pearson had at that time served as the team “bus.” It was spacious enough to transport the whole team to the games, Burttram said.

Marcus H. Pearson actually held patents on two different plow designs. The 1907 patent was for improvements to make the wooden plow more durable and easier to manufacture, according to his application to the U.S. Patent Office. This farm implement also had adjustable handles and a design that would “take the ground better and … not choke up as rapidly as the ordinary plow.”

That plow and his Pearson Fence Stretcher — to keep wire fencing from tangling during installation – received a blue ribbon at the 1907 Alabama State Fair.

In 1951, he received his second patent, this time for a “regulator for flow of material from a hopper” affixed to a plow.

The hopper, explained Burttram, distributed guano (fertilizer) simultaneously with tilling.

The patent application states that the design offered “lever control without stopping use of the hopper, adjustment without a ratchet or wrench, (and) locking in a fixed position without a tool.”

Burttram quite literally had a hand in the manufacture of this model when he was but a lad of 10 years old.

“Tommy’s first job was working for Granddaddy Pearson,” said Mrs. Burttram.

With a chuckle, Burttram recalled that his grandfather did not ask Burttram if he would like a paying job. Instead, Pearson asked the boy if he would like to have a Social Security number.

Having a Social Security number was something to be envied, so Burttram naturally wanted one. When he received it, his grandfather put him to work painting distributor boxes on plows.

Burttram said he was paid 10 cents for each box he painted.

“I thought I was really something,” Burttram said with a grin.

Mrs. Waid warmly recounts going with Pearson to sell and deliver his plows. Traveling to Oneonta or Blountsville or wherever made the preteen girl feel pretty special.

Mrs. Waid warmly recounts going with Pearson to sell and deliver his plows. Traveling to Oneonta or Blountsville or wherever made the preteen girl feel pretty special.

She and Burttram said Pearson’s blue Studebaker pickup served as the delivery truck. All these years later, Mrs. Waid parks her automobile under the same carport where Pearson kept his Studebaker.

Also, one of the 1951 plows has a place of prominence on Mrs. Waid’s front porch.

At one point, Sears & Roebuck asked Pearson to put a gasoline engine on his plow as a prototype. It also had additional wheels for stability, Mrs. Waid said.

Through his lumberyard, Pearson established a legacy in several churches in the area, Mrs. Waid said.

For example, Pearson assisted in 1926 with the manse of Springville Presbyterian Church, which is noted by an historical marker, Mrs. Burttram said. (Incidentally, Mrs. Waid is secretary at that church.)

For Burttram and Mrs. Waid, the lumberyard was not a place of business, but rather a land of adventure.

They explained that the freshly milled lumber was placed in triangular stacks to allow the wood to dry.

“They made great, little playhouses,” Mrs. Waid said of the triangles. She and playmates also would get into them to picnic.

“They made great, little playhouses,” Mrs. Waid said of the triangles. She and playmates also would get into them to picnic.

The imaginations of Burttram and his friends transformed the stacks into army bunkers.

And finally, we come to the story of how Pearson’s chicken house entered the annals of collegiate trivia.

In the mid-1960s, when Mr. and Mrs. Waid were married students attending Auburn University, Waid was a volunteer trainer and handler for the live War Eagle mascot. After a game in Birmingham between Auburn and its in-state rival, the University of Alabama, the couple spent the night with Mrs. Waid’s parents, who lived next door to the Pearsons.

Because the cage used for transporting the eagle was a little tight for an overnight stay, Waid decided to give the bird a place to spread its wings, so to speak. Thus, the little fowl guest was given accommodations out back in Pearson’s chicken house … minus the chickens, of course.