Movie gets special Pell City premiere

Story by Carol Pappas

Photo by Jerry Martin

It was a phrase and a sentiment Sgt. Matt Bein borrowed after multiple deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan as a Marine sergeant, but he says it describes life after war best. “We were ready for anything … until we came home.”

It was a phrase and a sentiment Sgt. Matt Bein borrowed after multiple deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan as a Marine sergeant, but he says it describes life after war best. “We were ready for anything … until we came home.”

He had been wounded by IEDs, improvised explosive devices, more than once on his deployments, but it never deterred him from the fight until the last one.

On a foot patrol in Afghanistan, he set off what he now believes to have been a remote IED, and he suffered brain injury. “I remember waking up in a corn field … soggy mud. My right leg was buried in the mud, and I thought I had lost it.”

When medics put him on the stretcher, he could feel that his leg was still intact, and he thought, “Thank God, I still had all my limbs. I’ve got everything. I’m good. I’m good,” he told them, and he got off the stretcher to walk the rest of the way.

He took one step, “fell flat on my face,” and then noticed the ground covered in blood.

A medivac helicopter was on site within 20 minutes, and he was on his way to medical care. “I was in and out of it from there. The only thing I could think about was just breathe, just breathe,” he said.

While civilians might think the rest of the story is a ticket home and return to normal life, for soldiers like Bein, there is a new definition for normal. Coming home is a whole new battleground for them, full of challenges, adjustments, coping and simply trying to survive.

Today, Bein is involved in helping other veterans come home, to talk about their experiences, their fears and get them the resources they need. He is part of a program called MAPS, Military Assistance Personal Support, and the St. Clair County-based group may be the first of its kind.

For Bein, the road has been a long one. For two years, he never spoke of the horrors he had seen, the buddies he lost. He had lived for deployments, fighting, “avenging and honoring” his fallen brothers.

His injuries were so severe doctors couldn’t believe he was still walking. He had a blood clot in his brain. “‘With your brain injury you should be almost paralyzed,’” Bein said one physician told him when he walked into the office.

Through it all, he still believed that one day he would deploy again. He had friends who were deploying, and when he went to see them off, he took his young son with him. “When the white buses pulled up, my son started screaming frantically, ‘Don’t go, Dad! I don’t want you to go!’ He knew what the buses meant — you’re coming back or you’re leaving.”

Through it all, he still believed that one day he would deploy again. He had friends who were deploying, and when he went to see them off, he took his young son with him. “When the white buses pulled up, my son started screaming frantically, ‘Don’t go, Dad! I don’t want you to go!’ He knew what the buses meant — you’re coming back or you’re leaving.”

It was at that point that he decided to cooperate. The husband and father of three told himself, “I don’t need to do this to my kids and family anymore.”

He began to talk to his doctors. “I lost four friends. That’s why I was so intent on avenging and honoring their deaths. I can’t do my job in the civilian world.”

But one doctor’s response gave him pause, helped him see a different path. “He asked me, ‘If those guys were still here what would they say?’ ”

And Bein found the answer he is living today: “The best way to honor them is not to fight but to spread awareness about where we have been and find people that need help.”

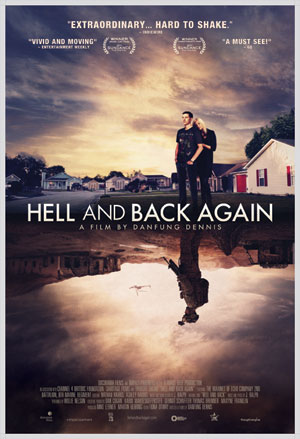

Bein and others are hoping that awareness will come through a new, award-winning documentary set to be premier in Bein’s hometown of Pell City. Hell and Back Again is the story of a marine platoon in Afghanistan — Bein’s platoon. It is the true story of what he and his platoon encountered in war, but it’s the rest of the story, too, the hellish, real-life drama of coming home.

It is the Alabama premier of the Academy-Award-nominated film that won the Sundance Film Festival, showing at the Pell City Center on June 14. A reception will honor the veterans at 6 p.m., followed by the film at 7.

Afterward, Bein and Sgt. Nathan Harris will hold a panel discussion for the audience, yet another avenue for building understanding.

A film producer was embedded with this platoon in Afghanistan in 2009, which was part of the surge ordered by President Barack Obama. The film is about war through the eyes of the platoon, but when Harris was shot, the film turns to the new battleground for him and centers on his nightmare of a journey home.

“We have done research, and 500,000 veterans will come home mentally or physically distraught — basically disabled,” Bein said. “We need to make our best effort to reach out to them and get hem the help they deserve.”

Being able to talk about it “eventually made me see how I could honor the guys who died.

“It was an amazing time — one of the greatest times of our lives. If given the opportunity, I’d do it again,” Bein said.

But he noted that he tries to encourage fellow soldiers with a poignant piece of advice: “We all did great things on our deployments. Don’t let that be the best thing we have ever done.”