Almost a century of fun: Camp boasts spirit and history

Story by Carolyn Stern

Photos by Jerry Martin

Submitted photos

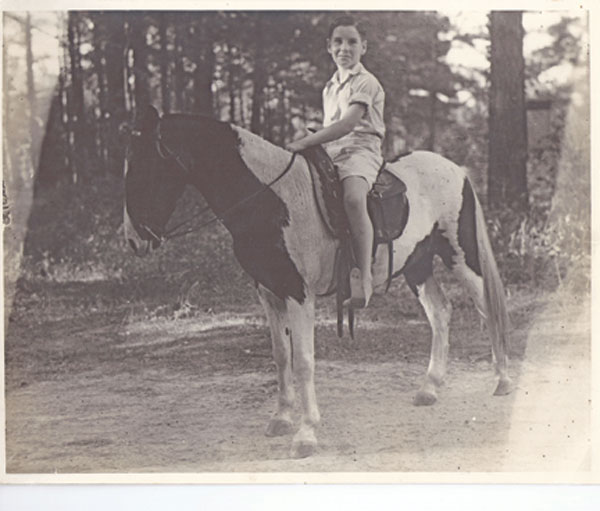

A wild place with a rushing creek and a waterfall; a chance to test your skill in canoes or on horses or to take on a Robin Hood pose by learning to handle a bow and arrow in archery class — the stuff of dreams for a boy or girl stuck in the city in the summer. Wild and wonderful, Camp Winnataska has made those dreams come true for almost 100 years.

A wild place with a rushing creek and a waterfall; a chance to test your skill in canoes or on horses or to take on a Robin Hood pose by learning to handle a bow and arrow in archery class — the stuff of dreams for a boy or girl stuck in the city in the summer. Wild and wonderful, Camp Winnataska has made those dreams come true for almost 100 years.

The secluded woodland camp close to Prescott in St. Clair County is not pretentious. It has no grand entrance nor elaborate buildings. But this collection of some of the best of the natural world and of human efforts holds a special place in the hearts and minds of those lucky enough to spend time here.

Hundreds of young people flood the camp during June and July, a week at a time. They swim, hike, work on crafts, learn to function as a team and sing, sing, sing. Everything they do during their week is based on the principles on which the camp was founded, but the way they’re presented is pure enjoyment.

A fortunate coincidence laid the groundwork for this dream to come true.

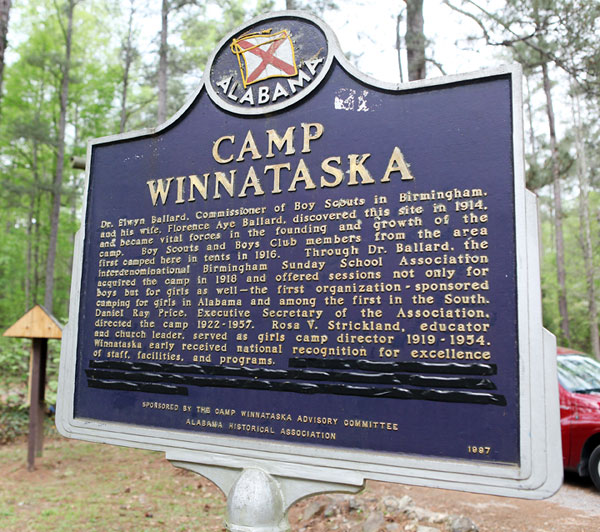

In 1914, Dr. Elwyn Ballard, the first commissioner of Boy Scouts in the Birmingham area, had been looking for an isolated retreat away from the city to establish a Scout camp. One spring day, he and his wife, Florence, took a ride in their Model T from Birmingham out past Grants Mill and through Leeds to Prescott to meet up with friends Lucien Brown and a Scout worker, Hewlett Ansley, at their favorite fishing hole. In the heavily forested area, the road narrowed to just a path between the trees, and they found the friends at Kelly Creek, which would eventually become part of Camp Winnataska.

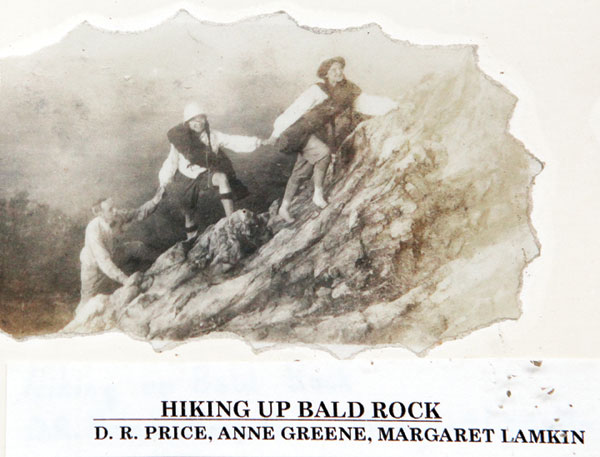

In her book, “Winnataska Remembered,” Katherine Price Garmon, daughter of future camp Director D.R. Price, quotes Florence Ballard, who was her aunt. “We fell in love with the place; the small pool, the falls, and the big pool below with towering cliffs … but its inaccessibility was one of its greatest charms.”

With Dr. Ballard’s strong endorsement, the Boy Scouts purchased some of the property, leased other acres and used it for overnight camping for two years. By 1918, however, the leaders decided that a camp closer to Birmingham was more suitable for their needs.

As luck would have it, the interdenominational Birmingham Sunday School Association had been thinking about starting a pioneer effort in religious camps for boys, and Dr. Ballard was able to bring the two groups together. The association board agreed to sponsor the program to accomplish “the fourfold goals of the association: physical, mental, spiritual and religious development.”

However, Rosa Strickland, a board member and a respected Birmingham teacher and Sunday school worker, had an objection to the plan. She insisted that a similar camp should be provided for girls. D.R. Price said, “Nobody argued with Miss Rosa.”

Other camps established around this time were taking Indian names, and Mrs. Ballard was asked to choose a name from a list of Indian words. Considering the waterfall was (and is) a primary feature of the camp, she chose Winnataska, which means “laughing water.” The number of arrowheads found on the property, along with the fact that there’s plenty of water at Kelly creek for use and to draw game to the area, indicated there had been a sizable settlement. This connection made using an Indian name even more fitting for this ancient land.

Affirming Price’s prediction, Miss Rosa’s proposal for a girls’ camp was accepted and had outstanding results when the first Sunday School Association camp took place in 1918. Out of an expected 75 boys, aged 12 through 15, only 31 registered. To be fair, some boys this age were already working. In contrast, the girls’ registration had to be stopped at 108, leaving some disappointed.

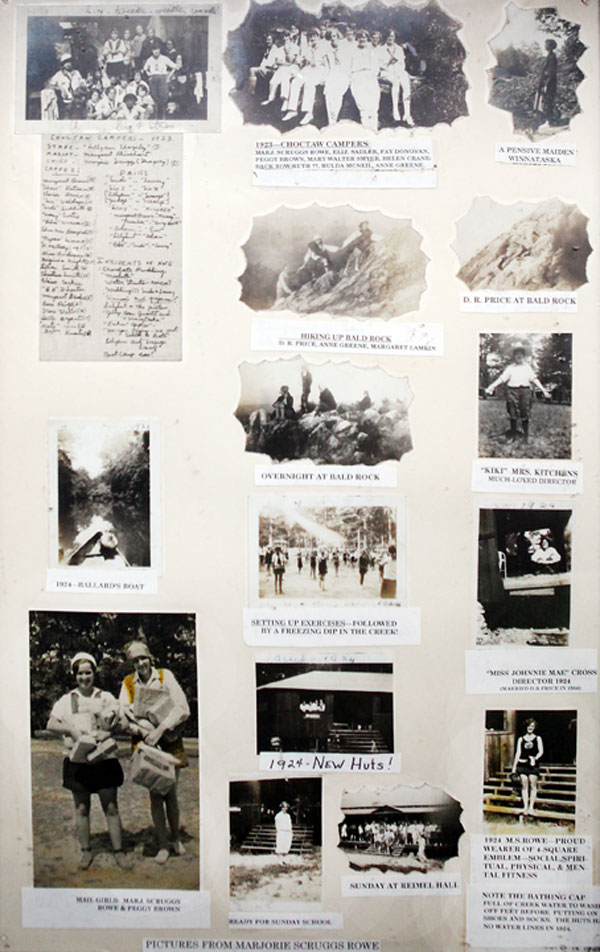

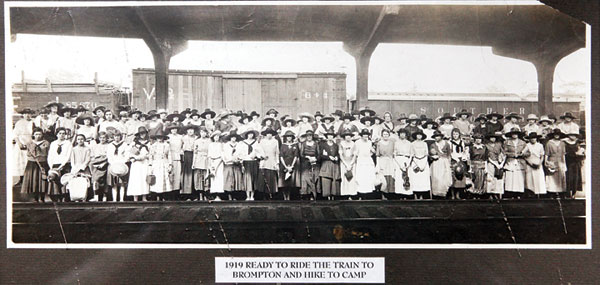

The earliest female campers (aged 15 to 17) boarded a train at Birmingham’s Terminal Station on July 17, 1918, got off at the Brompton stop and walked the final five miles to Winnataska, dressed in the long skirts and the hats of the day. (A photograph in Stockham Hall at the camp shows smiles on many faces and skeptical looks on others.)

As time passed, school-type buses were used to pick up campers at designated sites around Birmingham. Today, automobiles filled with whatever the camper feels is necessary (no cell phones are allowed) crowd the parking lot on registration days. Then the fun begins.

As time passed, school-type buses were used to pick up campers at designated sites around Birmingham. Today, automobiles filled with whatever the camper feels is necessary (no cell phones are allowed) crowd the parking lot on registration days. Then the fun begins.

The camper’s huts are named for Indian tribes: Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, Seminole, Chickasaw and Navajo. At the time camps for younger children began, the Sunday School Council was helping a religious education camp in Mexico. Winnataska began sending their Sunday worship offerings to that camp and used Spanish words to name the Chico (“little one”) cabins (ages 6 to 8): Siesta, Casa Nueva, Tienda and Adobe.

Each hut has leaders who encourage their groups to take pride in themselves and their surroundings. A simple task (to some campers) is to keep their hut clean. The fun comes when they are required to sing or cheer (loudly) whenever they’re walking outdoors. Each tribe has special songs and are encouraged to drown out the others.

“I’m Chickasaw born and Chickasaw bred/And when I die I’m Chickasaw dead./So, rah, rah for Chickasaw/rah, rah for Chickasaw/Rah, rah, rah./Bum-diddly-um-dum. Chickasaw!”

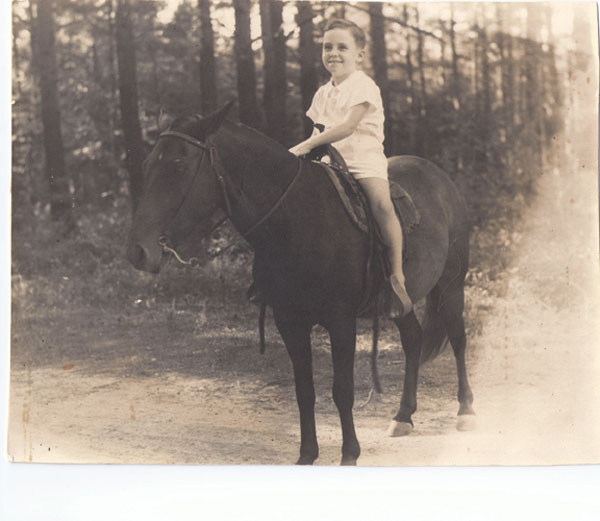

Staff members, Blackfeet (for boys) and Comanches (for girls), plan activities that encourage competition as well as teamwork — swimming, riding horses, canoeing and rope climbing. Campers take part with enthusiasm, all with the hope of being named the Honor Hut on the last day of camp.

Each day begins with Bible study in the 1930 Branscomb Chapel and ends at Hillside (which overlooks the waterfall) with an inspirational talk or a short worship service. Through all these specially planned activities, the camp continues to fulfill the fourfold purpose of the Sunday School Association — physical, mental, spiritual and religious development.

Mary Margaret Shephard is director of the summer camps, and Courtney Bean is the programs director. In 1922, D.R. Price became the first director. The camp was growing so quickly it was clear a formal leader was needed to oversee the property and activities.

Price held the position for 35 years. His immediate priority was to replace or update the existing housing for leaders and campers. Some structures were usable, and they were made more comfortable by being fitted with screens and new bunk beds. Before the luxury of the new beds, the 1920s girls sang a song about their old double-decker bunks, which had straw mattresses.

“In our bunk, in our bunk, where the hay comes trickling down, ‘till it hits you in the crown, in our bunk, in our bunk.”

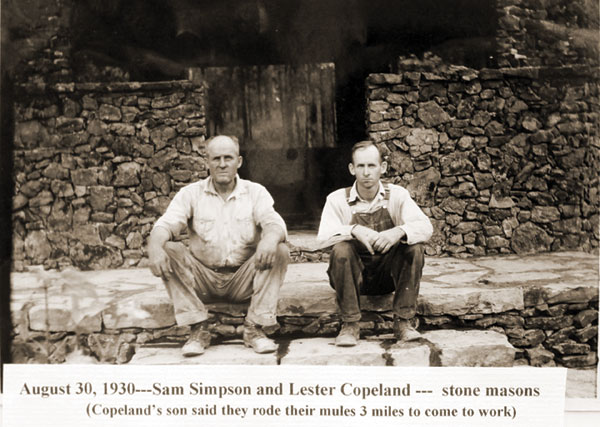

In 1930, property was cleared for Branscomb chapel, a circular open-air stone structure. Lester Coupland, a stonemason and carpenter who lived near Branchville, was the principal builder. Coupland’s son, Carl, says his father and his father’s uncle, Sam Simpson, rode their mules eight miles to the job.

As construction moved along, campers were recruited to gather rocks for the walls. Price reminded them that some rocks with color or distinct shapes were more attractive than others. He always told them to get the “pretty rocks,” his daughter says. The floor and seats are made with flat stone pieces from the creek below the waterfall.

Mrs. Garmon says the building’s round shape was chosen because Native Americans revered that shape, and Winnataska’s founders wanted to honor their tradition. Another custom, also thought to be from Indian lore, has continued to dictate movement in the chapel. One doesn’t walk straight across the floor from one doorway to another. To do so is believed to be unlucky. Movement goes around the circle.

Lester Coupland was asked to be caretaker of the camp in 1935, and he moved his family from their farm near Branchville to the premises. He remained caretaker until 1940. Friends of many years, Carl Coupland and Mrs. Garmon laugh about the times they and Garmon’s sisters played in the sand pile and all around the camp when their fathers were at work. Coupland says, “I was always smaller and the girls picked on me.”

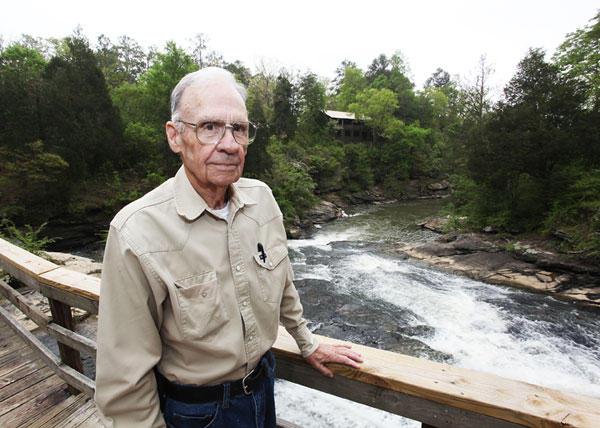

The “big hole” at the foot of the waterfall is a really good place to fish, Coupland says, but his favorite memory of living at Camp Winnataska is not about the fish. “I was able to hear the water rushing over the falls every night,” he says. “There’s no better sound in the world to put you to sleep.”

Kelly Creek runs through the property and eventually into the Cahaba River. Over the years, a number of bridges were built to join the two parts of the campgrounds, but heavy rains that raised the level of the rushing water washed them away. Finally, John Elon Stanley (caretaker of the camp from 1940 to 1961) and architect Walter Holmquist, with help from Roy Connor and Blackfeet Bingham Ballard and Fletcher Yielding, completed the bridge that carries campers over the falls today. The bridge was officially named for him at the camp’s 50th anniversary celebration.

The bridge isn’t the only sign of Stanley’s creative talent. He had been a railroad bridge builder and his impressive techniques can also be seen in the ceilings in Stockham Hall and Brewer Chapel. The beautiful and sturdy ceiling rafters were made of wood harvested from Winnataska land.

A number of structures and markers on the property honor those who have been key to the growth of the camp and in keeping alive what D.R. Price called “The Winnataska Spirit”.

They include Branscomb Chapel, Brewer Chapel, Reimel Hall, Stockham Hall, the Stanley Bridge, Rosa Strickland Lodge, Price Lodge, Norton Flagpole, Grayson Lodge and Grace Lake.

The present caretaker, Mark Buerhaus, was a Blackfoot from 1994 to 1998, and he just couldn’t stay away. He’s responsible for management of the 1,400 acres of camp property and for 55 structures that encompass 87,000 square feet. He says he couldn’t possibly do it all without his assistant, J.T. Braxton.

Buerhaus is a busy man with a family on the property and is on call 24-7. He’s an enthusiastic supporter of Winnataska and knows where the campers are at almost any time of the day or night. Yes, night: neon (ask a camper) and pirate nights, mission impossible hide-and-seek, country night and Indian night. All include some sort of costumes and the absolutely necessary singing and dancing. Wherever Mark is needed, he goes. Even if it’s into the night activities.

Mrs. Garmon, as the daughter of the camp’s first director, a camper herself and a niece of the Ballards, who found the property, feels a family responsibility about retaining the camp legacy. She tells about walking around the grounds one summer day and hearing very loud music coming from Stockham Hall. “I went over to check on the activities. The girls were being taught line-dancing.” She wasn’t quite sure about that or the music. But one little dancer caught her eye: “I thought, ‘If doing this gives her the feeling she’s a real dancer, that’s a good thing.’”

To date, more than 100,000 campers have sung the songs, hiked the trails and established friendships that last through the years. “Many campers are fourth-, fifth- and sixth-generations of families,” says Mrs. Garmon, “mostly from the Birmingham area. They wouldn’t think of going anywhere else.”

At a celebration of Winnataska’s 50th year, D.R. Price quoted a postcard sent home by a Chico camper: “Dear Mother, went swimming in the morning. I almost drowned. Camp is fun. This afternoon, I’m going to play with snakes.”

Why do kids like to go to camp? That about sums it up.

For a first-person account of what it was like to live at Camp Winnataska during the depression, check out the full edition Discover, The Essence of St. Clair online at ISSUU or in print.