Tales of survival from Omaha Beach

Tales of survival from Omaha Beach

Story and photos by Jerry C. Smith

Submitted photos

General Dwight D. Eisenhower spoke of Operation Overlord as “a crusade in which we will accept nothing less than full victory.”

To back up this solemn resolve, the Allies mounted the heaviest seaborne invasion in world history on June 6, 1944, a World War II event that would become known as D-Day. Hilman Prestridge, a 19-year-old draftee from Clay County, Alabama was there and lives on today to share his experiences.

The numbers are staggering, especially to moderns who haven’t lived during an era when literally the whole world was at war. For this operation alone, more than 160,000 Allied troops, 13,000 aircraft, and some 5,000 ships mounted a concerted invasion of Nazi-held Europe, including a 50-mile stretch of coastline in Normandy, France.

There were five distinct areas of beachhead assault, code-named Juno, Sword, Omaha, Gold and Utah. Of these, Omaha was the most difficult because of its hilly terrain and high concentration of concrete bunkers sheltering German cannons and machine guns.

PFC Prestridge of the First Infantry Division was in one of the first boats to land on Omaha, in the face of withering gunfire from fully-prepared, seasoned troops who had been expecting them for days.

Many drivers of the amphibious landing craft, called Higgins boats, refused to go into the shallowest water, fearing entrapment by grounding or by metal objects placed by the Nazis to snag boats and prevent heavy vehicles from coming ashore. As a result, many soldiers perished from drowning due to the heavy weight of their equipment and a malfunction of their flotation devices.

In the thick of the fight

“We had these life preserver things called a Mae West around our waist,” he recalls. “They were supposed to float up under our armpits when you filled them with air, but because we were loaded down with so much stuff, they couldn’t do that and just hung around our waists.

“Lots of men died with their feet sticking out of the water because all that ammo and grenades and backpacks kept them from floating upright.”

He gives high praise to his boat pilot, a brave Navy man who knew what was at stake and carried them into much shallower water that could be waded. But that’s when the real horrors began.

As soon as the front landing door was dropped, heavy machine gun fire began raking his buddies as they stepped off into the water. Many died right in front of the boat. Hilman says those stories about men jumping over the side instead are true, and that some owed their lives to that decision.

“Fact is,” he adds, “we missed the best landing spots because of heavy fog and wind but did the best we could anyway.”

It took several days to secure all five beachheads. “I found a low spot behind one of those tripod tank traps and slept with bullets whizzing just inches over my head.”

The casualties were appalling by any standard, with some 10,000 Allied wounded and more than 4,000 confirmed dead. But it could have been even worse.

“Because the weather was so bad that week,” Hilman explains, (German Field Marshal) Rommel had left the area to attend his wife’s birthday party, thinking we couldn’t land with that kind of weather. The Germans needed aggressive field leadership, and with Rommel gone, they were left without.”

“Because the weather was so bad that week,” Hilman explains, (German Field Marshal) Rommel had left the area to attend his wife’s birthday party, thinking we couldn’t land with that kind of weather. The Germans needed aggressive field leadership, and with Rommel gone, they were left without.”

As Hilman spoke of the horrors of that operation during our interview, he had to pause occasionally to gather himself emotionally. One of his most touching anecdotes concerned a tank that had finally managed to drag itself onto the shore, despite most of its unit having foundered in deep water, drowning their crews.

“I heard that tank behind me with those two big engines roaring,” he said. “It came right by me where I was pinned down by bullets over my head. When it passed me, I saw the word, ALABAMA, painted across the back end, and knew things were going to get better. He knocked a big hole in all that barbed wire, so we could get through.”

He also tells of the destruction of a particularly wicked German gun emplacement that had wrought heavy casualties and nearly brought the Omaha Beach assault to a standstill. “We saw the (battleship USS) Texas out there, not far from shore. He put it in reverse and backed way out for a clear shot, then blew that pillbox to pieces with one shell.”

After the beaches were finally secure, an officer informed Hilman that his brother-in-law, Fred Lett, had also landed on another beach, and told him where he could be found. The officer refused permission for Hilman to leave the area but added that his own Jeep was parked nearby with the keys in it, and Hilman was to be sure nobody bothered it. Hilman and Fred had a joyous reunion a short while later.

Hilman’s military career began upon receiving “a letter from Uncle Sam” right after graduating from Lineville High School. His basic training took place at Fort Bragg, NC, where he was selected for Field Artillery training in Maryland. “I was real happy with that idea,” he said. “Artillery gets to stay way behind the front lines, so I figured it was about the safest place to be in a war.”

He relates that his gun crew got into a bit of trouble when they accidentally put seven charges of gunpowder in a field piece designed to use four. The gun survived, but the projectile went all the way into town, destroying a huge tree but luckily doing little other damage.

Those in charge were not pleased, but this was during wartime, so allowances were made. Nonetheless, for no stated reason, they moved Private Prestridge into Amphibious Landing school, eventually thrusting him right into the teeth of the enemy.

“I was worried about it at first,” added Hilman, “but the transfer probably saved my life. The guys I trained with in Artillery were all later killed in battle.

“We loaded up onto the Queen Elizabeth (ocean liner) and wound up in Glasgow, Scotland,” he relates. “We finally were deployed to some place I can’t name in England. The people there were real good to us, and I even got to meet Princess Elizabeth while she was visiting troops in the fields around Dorchester. She was the same age as me, but not yet queen.”

Hilman said none of those in his outfit knew anything about the plans for D-Day; they were simply told they would ship out on June 5th, but their move was delayed until the 6th because of bad weather.

He said the English Channel crossing was pretty rough, and a lot of soldiers got sick, especially after boarding the landing craft. “They told us the waves were 12 feet, but the number I believed was more like 20, but it didn’t bother me. The rougher the water, the better I like it,” he explained.

“We were told to jump off the ship and into the boats when the waves went highest, but a lot of guys broke their legs when they timed it wrong because we were so loaded down with field gear and ammo.”

Hilman’s outfit was stationed in France until all of Europe had been liberated, then they were transported by ship back to the United States for a 30-day leave before being reassigned to another duty. While America-bound on the destroyer SS John Hood, they were told that their next assignment would be an all-out attack on the mainland of Japan.

Fortunately, before this hellish invasion was launched, President Truman took more direct steps in 1945 to bring World War II to a close. Upon landing in New York, Hilman and his comrades participated in a ticker tape parade celebrating that victory and were soon mustered out of the service.

Upon returning to Alabama, Hilman married Vernie Cruise, his high school sweetheart, and settled down. He worked at various jobs that included 10 years at Dewberry Foundry in Talladega before settling down to a career as an electrician at Alabama Institute for the Deaf and Blind, where “I actually did more work for the school’s athletic department than electrical stuff.”

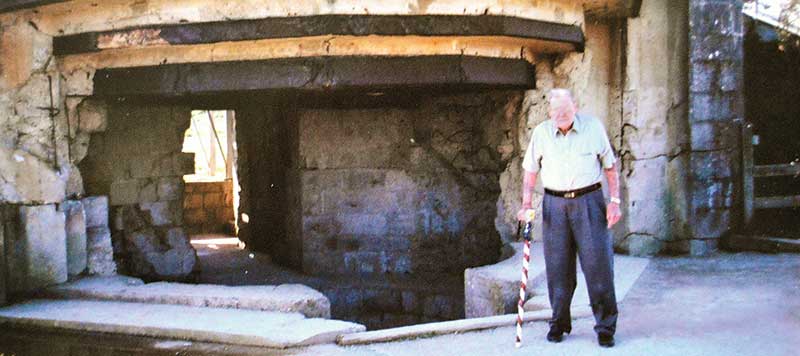

Now, a 94-year-old resident of Col. Robert L. Howard State Veterans Home in Pell City, Hilman Prestridge is far from retired. He’s been involved in many veterans’ activities, including group visits with his old comrades to various D-Day memorials in America and overseas.

While attending a 70th anniversary gathering at the D-Day Memorial in Bedford, VA, Hilman was greeted by a lady whose two brothers were with Hilman at Omaha Beach. They didn’t survive the landing. She was holding a Bible that one of them carried while serving, which had somehow found its way home.

He’s also revisited the actual spot where he landed in Normandy more than 74 years ago and has an album full of photographs he uses to illustrate their horrendous experience.

Hilman Prestridge is one survivor of only about 5,000 D-Day veterans estimated remaining. He is indeed an honored member of the Greatest Generation.

Thank you for your service, PFC Prestridge.

Just ask Harry Charles McCoy of Pell City.

Just ask Harry Charles McCoy of Pell City. “I’m a planner. … I got that from my parents: No matter what you do, you’re supposed to be prepared,” she said. “… To accomplish anything, you have to set goals and then take steps to achieve these goals. I feel that a good place to begin is in God’s Word.”

“I’m a planner. … I got that from my parents: No matter what you do, you’re supposed to be prepared,” she said. “… To accomplish anything, you have to set goals and then take steps to achieve these goals. I feel that a good place to begin is in God’s Word.”

“My own personal plan is to start at an entry-level position, then I want to go back to take more classes to get more certification.”

“My own personal plan is to start at an entry-level position, then I want to go back to take more classes to get more certification.”

And looking back, some call it “amazing,” others compare it to a fairy tale. But Tonya Tice Peoples, who came to Pell City from Lawrence County when her Dad, Mike Tice, became Pell City’s head football coach and hired Slater as the girls’ hoops coach, puts it more simply:

And looking back, some call it “amazing,” others compare it to a fairy tale. But Tonya Tice Peoples, who came to Pell City from Lawrence County when her Dad, Mike Tice, became Pell City’s head football coach and hired Slater as the girls’ hoops coach, puts it more simply: Like Slater, Tonya Tice Peoples became a teacher and coach. After working in NASCAR, Danielle Fields Frye is director of community engagement for the United States Auto Club (USAC) and lives with her husband and two daughters outside Indianapolis. Melissa Purvis McClain is an engineer. Erica Collins Johnson, like McClain, is still in Pell City. Alicia Moss Ogletree and Kathy Vaughn – a distinguished military veteran — are still in the area as well. April Hughes is in the fashion industry in New York.

Like Slater, Tonya Tice Peoples became a teacher and coach. After working in NASCAR, Danielle Fields Frye is director of community engagement for the United States Auto Club (USAC) and lives with her husband and two daughters outside Indianapolis. Melissa Purvis McClain is an engineer. Erica Collins Johnson, like McClain, is still in Pell City. Alicia Moss Ogletree and Kathy Vaughn – a distinguished military veteran — are still in the area as well. April Hughes is in the fashion industry in New York.

Although Wilson and fellow organizer, Tom Moody, said they were discontinuing the ride for the time being, “I have nothing but good things to say about the people of Moody, and the terrain was lovely,” Moody said. “The positive parts were the generosity and support of the people, particularly the mayor’s office and the chief of police and the government. And the beautiful scenery we had the riders go through it.”

Although Wilson and fellow organizer, Tom Moody, said they were discontinuing the ride for the time being, “I have nothing but good things to say about the people of Moody, and the terrain was lovely,” Moody said. “The positive parts were the generosity and support of the people, particularly the mayor’s office and the chief of police and the government. And the beautiful scenery we had the riders go through it.”

He makes it his business to get involved with every city government in the county as well as the County Commission, St. Clair Economic Development Council and other entities that share a common goal of moving forward. He knows every mayor and council member in the county by first name, and when he sees a need, he works to fill it.

He makes it his business to get involved with every city government in the county as well as the County Commission, St. Clair Economic Development Council and other entities that share a common goal of moving forward. He knows every mayor and council member in the county by first name, and when he sees a need, he works to fill it. “At that time, living in Pell City, entertainment, restaurants and shopping options were minimal,” Ellison recalled. “To shop for most things, we were having to go to Talladega, Leeds, Birmingham or Oxford. There just weren’t that many choices in Pell City for shopping. You would hear it in the community. People wanted more retail options.”

“At that time, living in Pell City, entertainment, restaurants and shopping options were minimal,” Ellison recalled. “To shop for most things, we were having to go to Talladega, Leeds, Birmingham or Oxford. There just weren’t that many choices in Pell City for shopping. You would hear it in the community. People wanted more retail options.”