Story by Carol Pappas

Photography by Wallace Bromberg Jr.

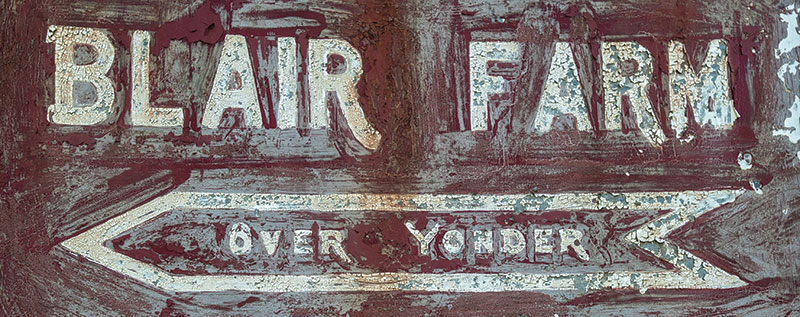

A weathered, vintage sign points the way from US 411 in Odenville. Tarnished by age, it’s hard to tell where its burgundy background ends and the rust begins. As you get a little closer, the white letters and arrow come into view, whimsically giving more specific directions: “Over Yonder.”

Follow the arrow’s path, and it leads you down Blair Farm Road to where else? Blair Farm.

In its 1950s heyday, its 240 acres hosted cattle, horses, ponies, a Clydesdale named Blue Boy Snow and a family by the name of Blair. Dwight Blair Jr., known as “Jobby,” bought the farm in 1952 and moved there with his wife, Margaret Drennen Blair, and their 2-year-old son, Dwight Blair III. Little sisters Dana and Carol would follow in the years to come.

It was the beginning of a new story for a World War II hero turned stock broker turned horse trader — or better yet, trader of all sorts — said his son Dwight III, now a prominent Pell City attorney. “He was a real wheeler dealer.”

His father would advertise horses and ponies for sale in the Birmingham News, and families would usually arrive on a Sunday to look them over. “Kids would become enamored with the ponies,” Dwight said. “They would say, ‘Dad, please let us have this pony!,’ and the father would say they would come back.” The thinly veiled excuse was they didn’t have a truck with them.

But Dwight says his father was not to be deterred from the sale. “He was a master at removing the back seat of a four-door car” to show kids and father alike just how those children’s dream actually could come true.

“Many a pony went from here with their head stuck out of the back window,” he said. Before they drove away, the wheeler dealer always added: “If it doesn’t work out, I’ll give you half of what you paid.”

The stories of his father aren’t always as lighthearted. In 1943, he was a bombardier in the Army Air Corps and was shot down in North Africa. He was in his turret, firing at a German plane and killed the fighter pilot.

The German plane started a nosedive and then quickly reversed direction, clipping the nose of the American plane. It spiraled to the ground, killing seven of his father’s crewmates. Only he and one other survived but were captured. He was wounded in his left leg, and 15 pieces of shrapnel remained. Reported missing in action, he spent more than two years in a German prison camp, escaping one time by jumping off a train. But he discovered he could not get far because of his leg injury, and he was recaptured.

In 1945, although presumed dead since his capture, he was released in a wounded prisoner exchange and headed back home to a hero’s welcome reported on the front page of the Age Herald, which later became Birmingham Post-Herald.

He went back to school at The University of Alabama and after graduation, he did post-graduate work at Wharton School of Business in Philadelphia and became a stock broker in Birmingham.

In 1946, he married Margaret Drennen, who was from a prominent Birmingham family. “Her father asked her, ‘Are you sure you want to live out in Odenville, where you will have nothing but chickens and horse manure?’ And she said, yes,” her son recounted the story his mother told him.

In 1952, they bought a small farm where Moody High School is today, but sold it and quickly bought the 240 acres on both sides of what is now Blair Farm Road.

He remained a stockbroker until 1958 when he decided to leave the big city working life behind for good and sell horses, ponies and cattle full time along with running a tractor and car lot in Leeds called Traders Inc.

He had about 50 head of cattle and 20 to 30 horses and ponies along with the farm’s familiar fixture — Blue Boy Snow — on the sprawling open pastures. “They were everywhere,” Dwight recalled as he motioned around the property. A monument to the Clydesdale, a Blair Farm resident from 1959 to 1991 who weighed more than 2,000 pounds, still stands in the shade of a towering oak tree in one of those pastures.

Today’s Blair Farm looks a bit different than those early days of wide-open pastures and a homeplace probably built in the 1890s. It was struck by lightning and burned to the ground. It was replaced in 1953 with the house passersby see now. A barn, believed to be built in that same turn-of-the-century time, still remains. Its square nails rather than round ones hint at its age. “It’s amazing it has weathered time like it has,” he said, noting that its only change has been adding a metal roof.

Today’s Blair Farm looks a bit different than those early days of wide-open pastures and a homeplace probably built in the 1890s. It was struck by lightning and burned to the ground. It was replaced in 1953 with the house passersby see now. A barn, believed to be built in that same turn-of-the-century time, still remains. Its square nails rather than round ones hint at its age. “It’s amazing it has weathered time like it has,” he said, noting that its only change has been adding a metal roof.

Other weathered barns and sheds are scattered around the property.

Austin Dwight Blair, the fourth Dwight in the lineage, now helps his own father with upkeep of the land. It helps to have Sheriff Terry Surles and Probate Judge Mike Bowling cut hay from it for their cattle. And friends and family come there to relax, skeet shoot or hunt. “It’s a place where everybody comes and feels comfortable,” Austin said.

Now a broker in commercial real estate for LAH in Birmingham, Austin likes returning to the place he rode horses as a child and had his very own pony, Freddy Boy.

For Dwight, it’s full circle. Up to about age 13, he thought it was a wondrous place. But teenagers tend to gravitate toward more action, and he took advantage of every opportunity to spend time away from the farm with friends in Leeds and Birmingham.

Then it was off to college, a scholarship to play running back at Vanderbilt University and later, law school at Cumberland School of Law.

In the midst of a successful and understandably busy career, Dwight likes coming back to the quiet of what has become a “weekend place” now. He raises pheasant and quail, and a couple of German Short Haired Pointers named Hansel and Gretel seem as content to call it home as his father did.

It is a story not unlike countless family farms in and around St. Clair County. They, too, have weathered time with their own tales to tell.