The beauty is forever yours

Story by Roxann Edsall

Photos by Mackenzie Free

and Roxann Edsall

John Liechty and Richard Edwards chat about old times as they turn along a switchback on Slab Creek Trail at Big Canoe Creek Nature Preserve in Springville. The two have spent countless hours hiking together over their nearly three decades of friendship.

Edwards got Liechty hooked on hiking when the two worked at the same company in Columbia, South Carolina. The friendship grew when the two moved their families to Birmingham to open a new office for that company.

Liechty has since moved back to Tennessee, where he was born, but hiking, and their passion for it, continues to be the thing that brings them back together.

The Big Canoe Creek Nature Preserve has been open less than two months, but the word is out about this hidden gem.

Liechty and Edwards heard about it in a newsletter update from the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Recourses. “We’ve done a lot of hiking, lots of backcountry stuff,” says Liechty. “The trails here are great with the elevation, the rise and fall. It’s all good. Y’all have a good thing here.”

The 422-acre Big Canoe Creek Nature Preserve is a Forever Wild Land Trust property, owned by the state of Alabama and managed by the City of Springville. It boasts four hiking trails, for a total of 7.3 miles of trails. Creek Loop Trail is designated solely for hiking. Fallen Oak Trail and Slab Creek Trail are open to biking also, while hikers on Easy Rider Trail share the space with horseback riders. Benches along the trails offer a place to rest or to bird watch, with picnic tables and portable restrooms available in the parking area. While you can canoe or kayak the creek, there is currently not a put in or take out point on the property. Plans include adding pavilions for outdoor education.

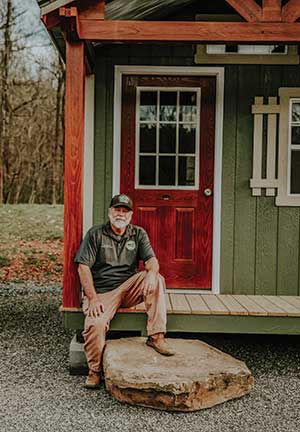

Preserve Manager Doug Morrison says environmental education is a top priority at the preserve. “Personally, I’d like to make 70% of our mission about education,” he says. “The recreation is going to happen. There are so many things to enjoy here. But if you can somehow get the message out that you can enjoy nature and not love it to death, that’s a good goal.”

Morrison’s personal motto is “explore and discover,” and it’s what he hopes people will do at the preserve. “I love to see kids outside learning and discovering things as they run around this place. There’s a lot to learn in nature. We had a home-school group out here yesterday, and they had a great time.”

With a little research, a visitor might learn that the area provides critical habitat for many aquatic creatures. One might discover that clean, moving water is necessary for mussels to thrive, and that the existence of several species of mussels in the Big Canoe Creek watershed is a testament to its cleanliness. One might further note that 18 miles of Big Canoe Creek has been listed as a “critical habitat” under the Endangered Species Act.

After moving to the area in 1999, Morrison began kayaking the creek and learned about the environmental importance of Big Canoe Creek. He helped to form the group “The Friends of Big Canoe Creek,” which at the time was mostly neighbors who loved the creek.

They learned about the critical habitat that is provided by the Big Canoe Creek watershed and about the threatened and endangered species that make their homes there, including the threatened Trispot Darter and the endangered Canoe Creek Clubshell mussel, found only in the Big Canoe Creek watershed.

The 50-plus-mile-long Big Canoe Creek, runs through the nature preserve and is touted as the “Alabama’s crown jewel in biodiversity.” More than 50 fish species can be found in Big Canoe Creek.

In 2010, and again in 2018, this exemplary biological diversity was explored and documented during what scientists call a “BioBlitz,” a 24-hour-long period where experts from various environmental fields survey and catalog all forms of life found in the specified area. Finding such biodiversity and both threatened and endangered species is what helped in the efforts, spearheaded by The Friends of Big Canoe Creek, to preserve and protect the land for future generations.

Had Morrison and The Friends of Big Canoe Creek not stepped in as advocates, the area might look very different today. When they learned of a developer’s plans to build a subdivision on the property, the The Friends of Big Canoe Creek petitioned the developers to make changes to ensure the creek would be protected.

When the economy took a downturn in 2008, the planned development stalled and gave members of The Friends of Big Canoe Creek a chance to talk to the landowners about nominating the land for purchase by the Forever Wild Land Trust.

Established in 1992, Alabama’s Forever Wild Land Trust purchases lands to expand the number of public-use natural areas to ensure they will be available to use freely forever. It took nine years to get the initial 382-acre parcel and another 40 adjacent acres approved for purchase, but by 2019, the combined tract officially became Forever Wild property.

“In conjunction with the Economic Development Council of St. Clair County, Freshwater Land Trust nominated Big Canoe Creek to be acquired by the Forever Wild Land Trust,” said Liz Sims, Land Conservation Director of Freshwater Land Trust. “We are elated to see such a large portion of the Canoe Creek watershed and its biodiversity protected, including the threatened trispot darter fish habitat.”

Since that time, Morrison, along with the The Friends of Big Canoe Creek, has worked with the City of Springville, the St. Clair County Economic Development Council and the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources to develop plans for the property.

In 2022, Morrison was hired by the City of Springville to officially manage the project. After 15 years of work to protect and preserve the land and creek, Morrison is finally seeing the joy it is bringing to visitors. He is seeing crowds of at least a hundred on weekdays, with weekends and holidays swelling to nearly twice that number.

Vicki and Kevin Folse heard about the preserve on Facebook and came out to hike. “It is absolutely beautiful,” says Vicki. “We took some time to sit on a bench on the trail and had some quiet time with God.” She thanked Morrison and all those who worked on the project for the opportunity to enjoy the property.

Jeff Goodwin lives just four miles from the preserve. “I come a couple times a week,” he says. “I’m a big hiker, so having this land to hike on this close is a huge benefit. And it’s way more interesting than walking through the neighborhood. I’m hoping they add some longer trails.”

While the trails are not the longest they’ve ever hiked, Richard Edwards and John Liechty agree they are well planned. Edwards, who grew up just minutes from a section of the Appalachian Trail, has spent countless hours hiking trails around the country. His longest hike was 160 miles on the John Muir Trail in California.

Six years ago his sight began to deteriorate due to a condition called nonarteritic anterior ischemic optical neuropathy. “I’m almost blind,” explains Edwards, “so rocks and roots are hard on me. These trails are really a dream.”

Even so, Liechty walks in front of his friend to alert him to any potential hazards. “We’ve kind of had a role reversal,” laughs Liechty. “He led me to hiking, but now I’m leading the hikes.” They agree that time spent together enjoying nature is good therapy.

Good therapy in the form of outdoor recreation can be enjoyed at Big Canoe Creek Nature Preserve Wednesday through Sunday 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. now through October, with closing time shifting to 5 p.m. from November to February. Admission is free.

If you go in the afternoon, take a good look at the metal fish on the left side of the entry gate. The color of the Trispot Darter changes as you move to the left and right. It’s just another thing that’s unique to this beautiful piece of paradise. And it’s forever protected, forever yours to enjoy.

Editor’s note: Big Canoe Creek Nature Preserve is located at 1700 Murphree’s Valley Road in Springville. If you would like to help support the preserve, you can make a tax-deductible donation online at bigcanoecreekpreserve.org.