Tracks from a bygone era cross St. Clair

Tracks from a bygone era cross St. Clair

Story by Jerry Smith

Photos by Jerry Smith and Jerry Martin

Submitted timetables from the Stanley Burnett Collection

Folks in Odenville, Alabama, often use the train trestle which crosses US 411 as a landmark for giving directions, but few except the very old are aware of the history of these tracks and of the tunnel at Hardwick Station, just a few miles east of town.

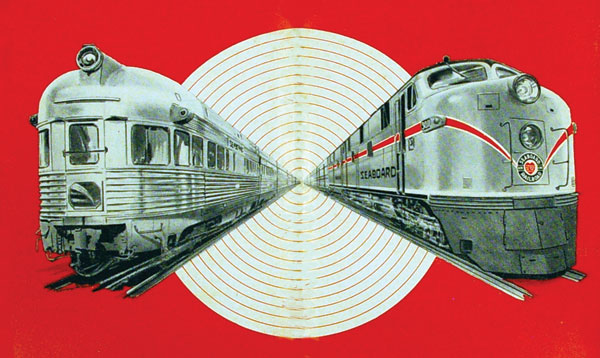

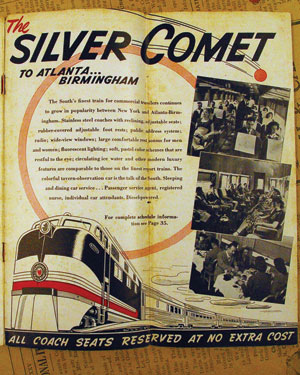

Both were built as part of Seaboard Air Line Railroad’s new trackage running from Birmingham all the way to New York City. For some 20 years, this line hosted Seaboard’s elite streamliner passenger train, The Silver Comet. Pulled by sleek new diesel engines, the Comet had everything a cross-country rail passenger might desire, including day coaches, observation lounge cars, diners and Pullman sleepers.

According to a 1947 Seaboard timetable, passengers who boarded the Comet in Birmingham at 2:35 p.m. could depend on being in New York exactly 25 hours later. The train passed through Trussville, Odenville, Wattsville, Wellington, Anniston and Piedmont before leaving Alabama; next stops, Cedartown, Atlanta, D.C., and eventually the Big Apple. The Comet competed directly with Southern Railway’s prestigious Southerner streamliner service.

Odenville resident Jack Stepp, a retired Southern engineer, said that even though it took a more circuitous route, Seaboard often beat Southern’s trains to common destinations.

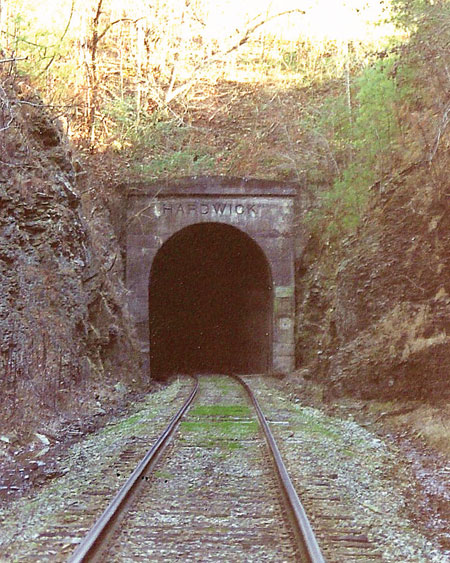

Like many civil engineering projects of the early 20th century, both Hardwick and its sister tunnel at Roper near Trussville were plagued by design errors from the beginning.

E.L. Voyles was a Seaboard road superintendent at the Sanie Division from 1916 until the mid 1920s, and his journals give a detailed look at how Hardwick and Roper Tunnels came about: “As Seaboard construction crews traversed their way west of Broken Arrow, through the mountainous terrain, it became evident that two tunnels would be necessary to reach Irondale.

“In early 1903, Hardwick and Roper Tunnels were bored. In an effort to save time and money, the big brass at Seaboard’s Richmond headquarters decided to build [both] tunnels to minimum standards. So the tunnels were supported by wooden frames cut from trees in the area. Keep in mind that in 1903, Seaboard had no tunnels anywhere on their entire system, so tunneling through mountains was not their forte. And they didn’t consider the consequences of using wooden frames positioned within feet of steam engine smokestacks blowing out fiery cinders when an engine was pulling at speed.”

“In early 1903, Hardwick and Roper Tunnels were bored. In an effort to save time and money, the big brass at Seaboard’s Richmond headquarters decided to build [both] tunnels to minimum standards. So the tunnels were supported by wooden frames cut from trees in the area. Keep in mind that in 1903, Seaboard had no tunnels anywhere on their entire system, so tunneling through mountains was not their forte. And they didn’t consider the consequences of using wooden frames positioned within feet of steam engine smokestacks blowing out fiery cinders when an engine was pulling at speed.”

Voyles continues, “Seaboard ran its first train into Birmingham on December 5, 1904. … In 1909, they realized their mistake concerning tunnel construction when an eastbound coal-burning freight highballing through Roper Tunnel … spewed an abnormal amount of fire and cinders. The huge wooden tunnel support system caught fire. Within minutes, the wooden supports were consumed by fire and collapsed onto the tracks.”

The disaster proved a blessing of sorts. Seaboard hired a team of professional tunnel people to rebuild both tunnels, reinforcing them with concrete instead of wood. Historian Joe Whitten of Odenville writes that the re-lining of Hardwick Tunnel alone consumed some 38,000 sacks of concrete over a period of nearly a year.

Because they had to excavate farther to clear the old structures, the rebuilt tunnels gained much-needed head and side clearance, which proved a godsend as trains eventually got taller and wider.

Trussville resident Hurley Godwin relates that adventuresome folks often entered a ventilation airshaft beside his home on Roper Tunnel Road using ropes to rappel down into the tunnel. The rail company finally fenced the area to protect these reckless climbers from themselves.

As for Hardwick Tunnel’s problems, Voyles relates, “The section of track between Odenville and Wattsville gave us fits. … They used a rail construction method known as “follow the contour”, rather than merge the track with the terrain. This was great when they operated short trains, but when a 100-plus-car freight pulled by four or five diesels snaked through the 180-degree turn and the back-to-back high angle curve tangents of Backbone Mountain, a tremendous amount of tension was placed upon the tracks in both directions.”

As for Hardwick Tunnel’s problems, Voyles relates, “The section of track between Odenville and Wattsville gave us fits. … They used a rail construction method known as “follow the contour”, rather than merge the track with the terrain. This was great when they operated short trains, but when a 100-plus-car freight pulled by four or five diesels snaked through the 180-degree turn and the back-to-back high angle curve tangents of Backbone Mountain, a tremendous amount of tension was placed upon the tracks in both directions.”

If one looks at this stretch of trackage on a satellite computer map such as Google Earth, it appears to be a long stretch of railway curled into two tight loops as it follows contour lines in the valley east of Hardwick Tunnel, a feature which train crews called the Rope.

One major derailment resulted in several engines and railcars plummeting into a ravine. Especially prone to damage and derailments during extremely hot or cold weather, the Rope eventually forced an end to Seaboard’s passenger service on that line in 1967, although at one time they had been running four passenger trains and six to eight freights per day.

The area was also prone to landslides, so elaborate cable networks were strung along rock cliffs to automatically trigger alert systems when rocks fell onto them.

But Hardwick Tunnel’s woes were not limited to the tracks beyond.

Approached on a curved track from the west, the tunnel itself is also curved inside. You cannot see light at the end of this tunnel (according to an anonymous observer). Voyles explains, “The track alignment through Hardwick was a tough section to maintain. … We constantly checked the rail for deterioration created by long periods of moisture that accumulated inside the tunnel. By the time an engineer could spot a broken rail inside the curved … tunnel, it was too late.”

Voyles says Odenville was a flag stop for local passenger trains, whereas Wattsville was a regular mail stop. He also relates that the conductor would drop off lunch orders while stopped for mail in Wattsville, and they would be ready at a trackside cafe when the train reached Piedmont.

In earlier days, a short line called the East & West Railroad connected Georgia Pacific’s line from Pell City to the Seaboard line at Coal City. Its wide roadbed, called Railroad Avenue on old maps, also hosted street traffic. Eventually this line was closed, the rails removed, and the street renamed Comer Avenue. It runs at an odd angle to every other street in town, passing by Pell City Steak House and the old Avondale Mills property before crossing I-20, and then toward Coal City.

As years passed and rail traffic dwindled, Seaboard went through various business mergers, eventually becoming part of CSX Transportation. The Roper-Hardwick portion is now leased by the Alabama & Tennessee River Railway (ATN) as part of a 120-mile freight short line from Birmingham to Guntersville.

Many segments of Seaboard’s old trackage have since been removed entirely, with some of their roadbeds eventually joining the Rails-To-Trails project. The well-known Chief Ladiga Trail is a fine example.

It runs on the old Seaboard roadbed from Anniston through Piedmont to the Georgia state line, where it continues as the Silver Comet Trail, with a combined length of some 100 miles. Legislation is afoot to make it part of the Appalachian Trail.

Those seeking physical fitness or outdoor recreation can get on the rail-trail at any crossing, and walk, run, jog, bike, rollerblade or whatever. It’s paved all the way, with no grades of more than 2 percent, so it’s also great for wheelchairs and baby strollers. Motorized vehicles are banned.

Want to visit Hardwick or Roper Tunnel? DON’T! All railroad tracks are the property of rail companies. Walking on any tracks is considered trespassing on private property.

Besides, it can be very dangerous.

Hardwick, for instance, is approached through a long, narrow, curved gap with steep sides that allow little room for escape if a train is coming. Also, as mentioned before, you cannot see through the tunnel, so an oncoming train might not be detected until it’s too late.

Best to explore railroad features on the printed page instead.