Story by Joe Whitten

Submitted photos

“Any person or persons who shall attempt to teach any free person of color, or slave, to spell, read, or write, shall upon conviction thereof of indictment be fined in a sum of two hundred and fifty dollars.”

This doleful Alabama law underscores the importance of education. Enacted in 1833, the law aligned with other Antebellum states’ laws which resulted from literate slave Nat Turner’s brief rebellion of 1831. Until then, slaves could be openly taught to read and write. Turner’s Rebellion ended in three days, and he was hanged.

Sometimes referred to as the “Black Moses,” Nat Turner was literate, preached from the Bible and influenced both races. From his rebellion, slave owners realized that educating slaves was dangerous. Therefore, soon after Turner’s execution, slave states began passing laws forbidding educating Blacks – slave or freedmen. Ex-slave Frederick Douglass would later write, “Knowledge makes a man unfit to be a slave.”

So, it’s no wonder that after the Civil War and toward the end of Reconstruction in Alabama (1874), freed slaves began organizing their own churches and schools. Established Dec. 17, 1868, the Alabama Black Baptist Convention urged their members to foster education through the local churches. In his history, Uplifting the People, Three Centuries of Black Baptist in Alabama, Wilson Fallin, Jr., records: “In 1870, the convention advised its churches ‘to build schoolhouses and churches in their own means, declining all union with others, unless absolutely necessary.’”

In St. Clair County, though, Ashville’s Black citizens had the “union” and support of White citizens in establishing the first school for children of former slaves. Old St. Clair County records show that on April 15, 1872, Pope Montgomery and wife deeded to the Methodist Episcopal Church a building to serve as a church and a school for “colored children.” That church was named St. Paul’s and continues today.

About 90 years later, this school evolved into Ashville Colored High School and in 1965 to Ruben High School.

According to Mrs. Bessie Byers’ valuable handwritten history of the school, the 1872 school began with two teachers who “were qualified to teach by having passed the teachers’ examination.” Attendance increased, and in a few years, more teachers were added, and both St. Paul’s Methodist Church and Mt. Zion Baptist Church served as classrooms for grades 1-7. Students sat on the church benches. Potbellied stoves supplied heat, and the men provided the wood and pine knots for starting the fires.

The school had no PTA, but parents and community came together to support education. Mrs. Byers writes, “The parents began having ‘Saturday Nights at the Hall.’ Admission was 25 cents, and every child who came was given 25 cents to spend on goodies, such as parched peanuts, cookies, and drinks. The money collected went to the teachers to purchase blackboards, chalk, erasers, and other necessities.”

These Saturday nights not only provided teachers with essentials but also brought the community together for fellowship. Those attending enjoyed spelling bees, poetry readings, games and singing. This community camaraderie has all but vanished in the whirlwind of today’s business.

As years progressed, music became part of the curriculum. Many of the students had natural musical gifts though they never had lessons. Mrs. Byers wrote of Ila and Eva Byers, “They could play any melody once they’d heard it, although they’d never taken piano lessons. Each day,” she recalled, “a time was set aside when lessons were put aside and every child sang, filling the building with the sound of beautiful old Spirituals.” She mentions that four graduates of Ashville Colored High School formed a quartet called The Happy Four and sang to groups as far away as Chattanooga. If they added a fifth member, they called themselves The Happy Five.

Margaret Bothwell LeFleur, class of 1963, recounted, “We had a little group of us girls called The Red Skirt Gang, and we used to sing the songs of the day – like Sincerely.” Gloria Williams, Gloria Woods, Pauline Mabry, Doris Turner and Margaret sang with the group.

By 1935, the school needed a new building. Mrs. Byers recorded that the County Board of Education, led by Superintendent of Education James Baswell purchased from Jim Beason three acres on the “hilltop known as Jim Beason’s pasture,” where the Board constructed a three-room frame building.

“It was a neat building,” she wrote, “painted white, with large classrooms and numerous windows. It was known as Ashville Colored High School, with grades one through 12.” The new school had running water but no lunchroom. Attendance grew quickly and the board added two more rooms. Five teachers gave instruction.

Earlier times

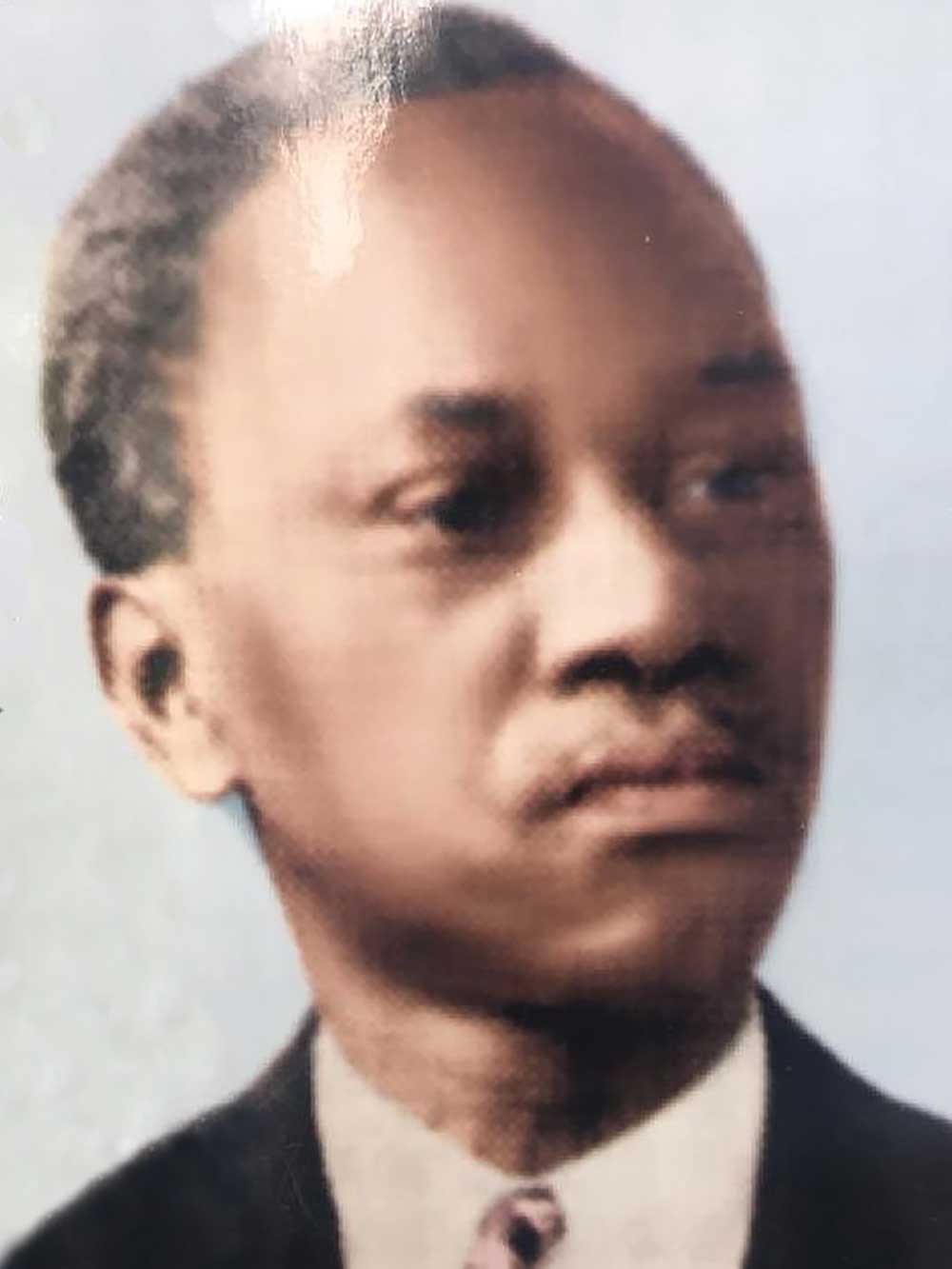

Let’s go back to1897 for a moment, for that year in Ashville was born to Wash and Sarah Yancy a baby boy they named Ruben. Sarah Yancy’s 1963 obituary lists Ruben’s siblings: Della Mostella, Gordan Yancy and Myrtis Noble. Ruben was the one destined to move Ashville’s Black school forward in the 1940s when he was known as “Professor Yancy,” principal of Ashville Colored High School.

Information about Professor Yancy remains scant. Where he attended college seems a mystery, although 91-year-old Boone Turner recalls that Professor had several college degrees and “When school was out for the summer, he would take off to Chicago and take up classes.”

He probably started at Millers Ferry, Wilcox County. He was teaching there when at age 21, he enlisted in the U.S. Army on Sept. 28, 1918. Teachers were exempt from registering, but he patriotically enlisted. However, the war ended less than two months later, and he received an honorable discharge on Dec. 26, 1918.

Just where he taught after the war and what year he arrived in Ashville to teach is elusive. By 1947, Professor Yancy had been appointed principal of Ashville Colored High School. Some local senior citizens recall him well. Joe Lee Bothwell recalled, “When he told you to do something, he meant it. He was all about you learning.” Boone Turner said, “I can tell you he was a good man. He was the principal of the school and taught classes.” His influence was on both Black and White communities, Boone said. When White parents whose children needed tutoring in math, they sent them to him for tutoring. Jay Richey, whose dad, J.W. “Shag” Richey, principal of Ashville High School and later St. Clair superintendent of education, recalls hearing stories of the math tutoring and how “extremely intelligent” Professor Yancy was.

As a well-educated, hometown man, Professor Yancy was respected throughout Ashville. Mrs. Byers observed that he “commanded the respect” of both students and parents. He also knew his students deserved a better school building with a lunchroom and library, and he set to work to bring that dream to fruition. “White citizens of Ashville,” Mrs. Byers wrote, “helped Mr. Yancy plan the new building,” which took several years.

When Professor Yancy’s health forced him to retire, Lloyd Newton took over as Principal. On Feb. 26, 1958, Professor Yancy died, never seeing the fruit of his labor.

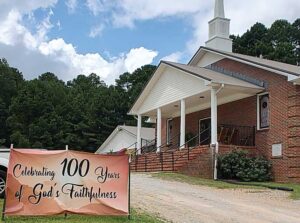

The community’s love for him moved them to successfully petition the board of education to rename the school for him. Therefore, at the dedication of the new building, Dec. 15, 1965, they changed the name from Ashville Colored High School to Ruben Yancy High School.

Eloise Williams recalled that after integration there was a move to change the school’s name, but Brother Clifford Thomas led the way in gathering petition signatures to present to the board of education to keep the name Ruben Yancy. The board approved. The school served the middle school for some years and now serves alternative education students.

Under Professor Yancy’s photograph in the dedication day program appears these words: “The school is being renamed in honor of the late Prof. Ruben Yancy who was a native of Ashville and principal of Ashville Colored High School from 1947 to 1956. Because of his humanitarian efforts, the community has grown and become a better place to live. His life was an exemplification of all that is embodied in ‘The Teacher’s Creed.’”

Another legend

Professor Lloyd Newton’s education career in St. Clair County made him a legend not only in Ruben Yancy High School but also in the integrated Ashville Elementary School.

Lloyd’s father was a cotton farmer in Sumter County, according to a retirement article in The Anniston Star, Aug. 11, 1985. His mother died when he was three and his father married again.

Erroll Newton, Lloyd’s son, recalled that after his dad graduated from high school, he lived with relatives in Fairfield, where several other relatives lived and worked. One of his aunts recognized Lloyd’s scholastic aptitude and introduced him to the president of Miles College. He enrolled in Miles, lived with his aunt and worked his way through college.

The United States had entered World War II, and Lloyd joined the Navy where he was a first class motor machinist mate for four years. Erroll Newton says of his dad, “During WWII, the military was beginning to integrate all branches of service, and it was in the Navy that he developed his skill as an instructor.” According to the Anniston Star, “After working for Seaboard Railroad, the Navy, and (attending) Wayne State University in Michigan, he landed back in Alabama.” “It was after being discharged after WWII that he began his odyssey to further his career,” Erroll said. “He worked as railroad porter in the Ford Foundry and the Fairfield Foundry, and continuing college in Michigan.”

“Back in Alabama,” Erroll continued, “He ran a nightclub in Fairfield a while before Dr. Bell, president of Miles College, gave him a reference to teach veterans in St. Clair County. A St. Clair News-Aegis article of Nov. 14, 1991, states that Professor Newton returned to his home state in 1947 and that he spent 37 years in St. Clair County education.

Teaching veterans seems to be the beginning of his education career in St. Clair County, but at some point, he began teaching for Professor Yancy and taught until he became principal and was known as “Professor Newton.”

Thousands of children profited from his teaching and mentoring, and each has a memory, as does his son, Erroll, who spoke for himself and his deceased brothers Lloyd, Jr., and Paul when he said, “To me he was just ‘Dad.’ With me not having a mom, he played both roles, and he did a good job. When we came along, he kind of took the reins off, so to speak. It was like, ‘If you want to advance, I’m setting an example for you. You choose your own way, though.’ He was Dad; that was him to me.” And later he was Granddad to Terrell, Chery, Shawn (deceased) and Ryan and several great-grandchildren.

Margaret Bothwell LeFleur credits her teachers and Professor Lloyd Newton at Ashville Colored High School for much of her own success in teaching.

“All of our teachers were dedicated,” Margaret recalled. “Mrs. Marcelline Bell taught seventh- through 12th-grade English. We had textbooks, but we didn’t have a library. But she taught us the Dewey Decimal System even though we had no library to use that knowledge in. However, when I went to Bethune Cookman College, I knew how to use that system in a real library! Our teachers knew what we needed, and they did their best to compensate for the deficiencies.”

Margaret’s dad drove her to Attalla twice a week for piano lessons for there was no Black piano teacher in Ashville. She progressed quickly, and as a seventh-grader played for high school graduation. She accompanied the school choir, which Professor Newton directed. In college she majored in music, which led to her career of teaching music in the schools of St. Paul, Minn.

After Margaret’s mom bought her a typewriter and instruction book, Professor Newton helped her learn typing, and she became an office assistant to him during her high school years.

Eloise Williams remembers Professor Newton as one who “set examples for the kids, and he and the teachers did a good job educating us.” She recalled that he disciplined when misbehavior called for it.

She also knew him as the principal of Ashville Elementary School where her son attended the integrated school. “When the law passed,” she said, “the school had to integrate. Our kids had a hard time. The Whites weren’t used to the Blacks, and the Blacks weren’t used to the Whites. It was new thing for all of them. It didn’t work for a while, but then it smoothed out, and they began to get along with each other.” Mrs. Williams is lovingly known as “Sister Ella” in Ashville today.

Most folk from the 1960s years agree that Professor Newton’s respect by both races, his professional demeanor, and his calm guidance helped ease tensions of integration in Ashville.

When Ruben Yancy ceased being a Black school in 1969, the County Board placed Professor Newton over the elementary grades at Ashville High School (grades K-12) where J. W. “Shag” Richey served as principal. When he moved to the central office of the county board, Mr. Keener became principal of Ashville High School and Professor Newton, principal of Ashville Elementary School, where he served until he retired in 1985.

Jay Richey said of Professor Newton, “He was first class, and a loyal school man to my daddy, and I loved him dearly. Whatever job needed to be done, Mr. Newton did it well.”

Recalling his father’s career, Erroll added that his “Dad considered Superintendent D.O. Langston a great asset to him” during his administration, and his “faculty members assisted him over the years.” He also mentioned the love of his “endless number of students.”

Professor Newton’s students and teachers hold his memory dear. Maurice Crim started teaching for Professor Newton in 1957 and described him as “a man of integrity who was very supportive of his teachers. There were no problems for we all got along well there.”

“He had a deep booming voice that made you automatically respect him,” student Joy Walker Raysaid. Others, too, recalled his voice and his love of singing.

Glorine Williams became his daughter-in-law when she married Erroll Newton. “Growing up, I remember Mr. Newton coming to my home, and he always talked about the importance of education, attending school and doing your best no matter what. He believed in helping students, and he didn’t show favoritism with anyone. Everyone was treated equal.”

His teachers at Ashville Elementary speak fondly of him. “Mr. J.W. Richey hired me,” recalls Beth Jones, “but Mr. Newton was my first principal. I remember ‘the Professor,’ as Mr. Richey affectionately called him, as a strict father to his teachers. He also had a firm but kind rapport with his students.

“My first year, I had 43 fourth-graders. That year, Mr. Newton reminded me of something very important. The two of us were standing in the hallway at dismissal time, trying to find ways to get poster projects home. There was one last poster with no way to get it home,” she said.

“As a new teacher and taking this lighter than I should, Mr. Newton chided me; for that last poster, even though not the best, demanded the same respect as any other. That poster was his work and important to the child. The child who made it was important. As a young, impressionable teacher, I never forgot Mr. Newton’s words to me, words that colored my entire career.”

Susan Kell also has memories of the professor. “When Mr. Newton came to Ashville elementary, I was teaching first grade. I later became librarian and worked with him until his retirement.

“Mr. Newton cared deeply for the Ashville community, especially the young children of Ashville Elementary. The 1970s were before school nurses, so he took care of the sick and all the playground ‘boo-boos.’ He once removed a tick from a child’s ear.

“This, however, is one of my favorite Mr. Newton stories. There was a disturbance in the lunchroom, so I walked to the table to investigate. I heard, ‘Is too.’ ‘Is not.’ ‘We do.’ ‘Do not.’ I asked, ‘What is the problem?’ and a child replied, ‘We do have a school doctor, and there he is,’ as Mr. Newton walked into the lunchroom.”

“He wore many hats other than principal – teacher, friend, counselor, singer, and yes, medical doctor!”

Professor Newton retired in 1986 and continued his influence in St. Clair County through the Alabama Retired Teachers Association, serving on the Committee for Protective Services, and in service to his church.

As a man of Christian faith, Professor Newton served as deacon and Sunday school teacher at Mt. Zion Baptist in Ashville. Well known for his basso profundo voice, he sang in the church choir and often sang solo.

Combining his love of singing with his love of children, one wonders if when he arrived at the empty school some mornings, he may have voiced the old children’s gospel refrain:

Jesus loves the little children,

All the children of the world,

Red and yellow, black and white

They are precious in His sight,

Jesus loves the children of the world.

“Children are the greatest thing in my life,” Professor Newton told Viveca Novak of The Anniston Star, and his loving influence continues in the multitude of lives that he touched in his lifetime.

Professor Newton, St. Clair County thanks you.