Quilts and quilters have compelling stories to tell

Quilts and quilters have compelling stories to tell

Story by Joe Whitten

Photos by Susan Wall

Submitted Photos

Gee’s Bend quilts, vibrant and spontaneous, have been exhibited and written about around the world, but for Claudia Pettway Charley, born in Gee’s Bend and now living in Pell City, quilts have been an everyday fact of life.

She grew up nurtured by the women whose quilts would one day be showcased in museums across the globe. It was a legacy, an art learned from her mother, Tinnie Pettway; her grandmother, Malissia Pettway; her aunt, Minnie Pettway; and other quilters of the close-knit community.

Sewn by descendants of slaves from a plantation on the Alabama River, these quilts have made Gee’s Bend and the quilters internationally famous.

From The Times of London — “The women of Gee’s Bend … have shattered artistic boundaries. Their bold, vibrant designs are as radically different from orthodox quilt patterns as Picasso was from anyone who preceded him.”

From The New York Times — “What makes this (Gee’s Bend) tradition so compelling is that unlike most quilts in the European-American tradition, which favor uniformity, harmony and precision, Gee’s Bend quilts include wild, improvisatory elements: broken patterns, high color contrasts, dissonance, asymmetry and syncopation. …”

Quilting originated in the Orient as padded garments, then made its way to Europe by way of returning 13th century crusaders, and eventually evolved into bedding.

Quilts came to the New World with the first settlers and were necessary in the home well into the 20th century.

Quilts came to the New World with the first settlers and were necessary in the home well into the 20th century.

In the second half of the 20th century, there burst upon both the quilting world and the art world the phenomena of Gee’s Bend quilts. In 2018 the Bend’s quilts again came to prominence through the official portrait of former First Lady Michelle Obama painted by Amy Sherald of Baltimore. Mrs. Obama’s portrait gown features quilt blocks associated with Gee’s Bend quilts. In 2018, Sherald visited Gee’s Bend quilters and had a grand time in Tinnie Pettway’s home hearing stories from the past told by Tinnie and her sister Minnie.

Gee’s Bend quilter and entrepreneur, Claudia Pettway Charley, is partner in the family-owned business and currently owns the registered trademark for that business, That’s Sew Gee’s Bend. In a recent interview at the Pell City Library, among an array of her quilts as well as her mother’s, she talked about her process of making a quilt. “Everything comes from the head and the heart — what the feeling is at that moment, that time when you put a piece together. No patterns, nothing like that.”

The fascination and beauty of a Gee’s Bend quilt is its spontaneity. Each quilt is a serendipity of seemingly haphazard colors and shapes that harmonize into a thing of beauty which sings to the observer’s soul.

A New York Times reporter wrote that the earliest Bend quilts “…came into being alongside gospel, blues, ragtime and jazz,” an era when strict rules of music composition were tossed aside. Think of trumpeter Louie Armstrong or pianist Thelonious Monk departing from the written notes and improvising his mood of the moment into improvisations.

Now look at a Gee’s Bend quilt and realize the placement of color, fabric texture and shape speak a language of mood or emotion, unhampered by strict adherence to geometrical pattern and form. The green-bordered Double Glory quilt by Tinnie Pettway (Claudia’s mother) is as lively as New Orleans jazz vibrating the night.

Now look at a Gee’s Bend quilt and realize the placement of color, fabric texture and shape speak a language of mood or emotion, unhampered by strict adherence to geometrical pattern and form. The green-bordered Double Glory quilt by Tinnie Pettway (Claudia’s mother) is as lively as New Orleans jazz vibrating the night.

Claudia acknowledged her quilts to be both improvisational and abstract — each quilt “is true to itself,” she said.

When asked her thoughts when beginning a new quilt, Claudia replied: “It could be your mood at that particular time; the weather; how you are feeling. If you’re feeling excited and happy, you may choose a lot of bright (colors) for the piece — I’m speaking of myself now. You just kind of know the direction you want the piece to go. It’s not just one thing; it could be a multitude of things that would make you choose certain fabrics and colors.”

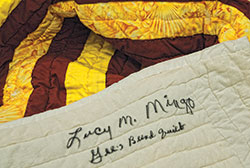

Tinnie Pettway’s thoughts on starting a quilt correspond with her daughter’s. “Fabric is not the problem,” she said. “My problem is the design — and I have no special design (in mind) when I’m making a quilt. I think of how I want it, and sometimes that don’t work out, and I just let that go. I take a portion of the quilt, and I lay it out on the floor, and I look at it. I turn it around, and whatever looks the best to me when I place it together, then that’s the way I sew it.” Her yellow-bordered Multi Block Crossroads quilt is a striking example of how successfully she works this technique.

The Bend quilters do have “traditional patterns,” Tinnie said; “…things like Grandma’s Dream, Nine Patch, String, or the one we call House Top — those are regular quilts that everybody makes. But I have no particular pattern. I just sew pieces together. If they look good, I sew the pieces together.

“And everybody who sees one (of our quilts) knows that that’s a Gee’s Bend quilt. It’s put together just as our mind tells us — most time with no set form and no set pattern. That’s how we do it.”

How did they get here from there?

To understand Gee’s Bend quilts, you need to answer the question, “How did Gee’s Bend quilts originate?” To answer that, you must know some of the history of this particular bend in the Alabama River. And to appreciate the abstract beauty of the quilts, you must understand the pervasive tension between despair and hope in their lives.

Joseph Gee, from North Carolina, settled in the Bend around 1816 and established a plantation in the rich, fertile river-bottom land. According to Harvey H. Jackson II in his Rivers of History: Life on the Coosa, Tallapoosa, Cahaba, and Alabama, Joseph died in 1824 and left the plantation and 47 slaves to his nephews still living in the east. One nephew, Charles Gee, moved to Alabama and ran the plantation until the 1840s. At that time, to settle a debt, Charles and his brother deeded everything to Mark H. Pettway. In 1846, Pettway and family with more than a hundred slaves made the journey through the Carolinas and Georgia and into what by then was called Gee’s Bend, Alabama.

Pettway brought change. Jackson writes, “… His slaves cleared more land, planted more cotton and built their master a ‘big house,’ which he named Sandy Hill. Gee’s Bend became, according to one student of the region (Nancy Callahan), ‘a dukedom in the vast Southern cotton empire,’ and there Pettway lived in splendid isolation. Deep in the heart of a bulb-shaped peninsula, almost entirely surrounded by the river, Mark Pettway was free to do whatever he wished, and he did.”

When emancipation freed the slaves, they all took the Pettway surname whether blood-related or not, and all stayed on the Pettway plantation, working as sharecroppers and tenant farmers. In 1895, Pettway sold the land to Adrian Sebastian Van De Graff, a Tuscaloosa attorney who ran the farm as an absentee landowner.

By the 1920s, Gee’s Bend was an isolated African-American community. Farmers sold their cotton to a merchant in Camden. The price of cotton dropped in the late 1920s, and without telling the farmers, the merchant held the cotton hoping the price would go up in a few years. All the while, he kept account of what they bought, to be paid for when the cotton sold.

The price of cotton did not go up before he died. His heirs saw only what the farmers owed — and the farmers’ held cotton had “disappeared.”

In 1932, the merchant’s heirs sent men to Gee’s Bend to collect. And collect they did, taking everything — household goods, cows, mules, pigs, seed for next-year’s planting. The pillaging left the people destitute.

Jackson quotes a Christian Century article by Rev. Renwick C. Kennedy, “In October and November, 68 families, 368 people, were ‘broken up’ or ‘closed out’ — Alabama phrases that described both a physical condition and a psychological state.”

The stricken people faced the winter with the real prospect of starvation. Jackson writes that they survived through the help of both the Red Cross and a compassionate Wilcox County plantation owner who provided assistance with cornmeal and food.

From this poverty came the quilters thrift of salvaging still usable portions of worn-out overalls and clothing to make cover to pile on beds for warmth in an unheated, cardboard-thin house. These quilts are documented in Gee’s Bend: The Women and their Quilts and The Quilts of Gee’s Bend.

Tinnie Pettway commented about this use of worn-out clothing, saying, “…In those old quilts, to have a different color…they would rip seams (of overalls), and where the seams had been folded, (it was) still holding its color. They’d sew it together.” This gave them shades of blue in the pieces.

She also told of the competition between the quilters. “They wanted to see which one could make the best quilt — even out of those ragged pieces they had. In spite of the lack of material, they used whatever they could find.” Tinnie and her sister, Minnie, made the quilt, Robust, of worn overall denim scraps. Note the splash of red in the lower right — a counterpoint of hope in a field of lonesome blue.

Claudia was asked, “Do you think any of the quilts reflected the distress of what the people were going through?”

She responded thoughtfully, “It’s possible. (When) you look at some of the old quilts and what they used for material — croaker sacks … overalls. … I think it was according to the attitude of the time, … using what they had available. They said to themselves, ‘We’re gonna survive regardless of what anyone says or what anyone does.’

“You know, growing up in the country like that, it makes you a survivor. Gee’s Bend was like a forgotten community — totally. So, we depended on each other. We depended on the farming, eating off the land, doing anything we could do at that time for survival. And it makes today seem simple.”

In Claudia’s quilt, Crimson Blues, she has created a sense of tension in the shapes and placement of red, blue and black pieces. The themes of despair and hope seem to throb through Gee’s Bend quilters’ blood and come to life in their quilts.

Drive for more than quilt-making

Not only was there a determination to survive physically, but there was also the struggle for basic citizen’s rights, such as the right to vote.

Tinnie Pettway remembers that well. “I went over to register to vote, and they put me in a little room in the courthouse. It just had one door. Finally, it got dark, and I looked up, and there was these three men standing right in the door looking at me. I just looked at them, and they backed out. I don’t know why they was looking at me, trying to frighten me or not. I don’t know. But they backed out, and finally I was able to register to vote. They sent me my card saying that I qualified.”

Claudia’s aunt, Minnie Pettway, recalled the same intimidation and that the officials threw away her first registration forms. “Threw them in the garbage!” But she kept trying. “A lot of people wouldn’t go. I guess they were somewhat afraid, but my daddy wasn’t afraid of nothing, so I just went along with him.” Finally, as a result of a court hearing in Selma, Minnie was a registered voter. “When we were declared registered voters, whenever there was an election, we went to the polls and voted.”

Tinnie, Minnie, and others from Gee’s Bend marched in Camden, the county seat for the right to vote. “Most of the people who was marching was not the educated people … many of them were afraid to march. They were afraid of their jobs — that they would lose their jobs,” Minnie remembered. “My daddy (Eddie Pettway Sr.), used to get truckloads of people and take them to Camden to register to vote, and they would put them all in jail. Then a day or two later, my daddy would go back with his truck and try to bond them out of jail. … Daddy went to get them, but they would go back a day or two later protesting again.”

Eddie Pettway Sr., who was Claudia’s grandfather, marched at Edmund Pettus Bridge with others from Gee’s Bend. “They ran over them with horses,” Minnie recalled, “and would spray them with tear gas. My daddy would drag the ladies out of the area where the tear gas was strong.”

The determination to keep on until rights were won seems to be sewn in Tinnie’s Gee’s Bend Geometric Trails quilt of multi-colored panels bordered by panels of red and gray — no curves in these trails, they lead straight ahead to the goal.

When asked if the young folk today realized the struggles of their grandparents, she replied, “They don’t, really. My grandkids, Claudia’s kids, they enjoy listening to the stories, but they just can’t imagine going through that.”

Not only could the younger generation not comprehend what the struggle had been, but neither could the crowds at the museums when Gee’s Bend quilters appeared at exhibits.

The women traveled from museum to museum for each exhibit of their “works of art” in galleries across the USA. “We would talk,” Tinnie remembered, “and tell the people how it was coming up in Gee’s Bend and the struggle we had here. … What we were telling (about our lives) was unimaginable (to them).

“When our bus would come in (to a museum), they’d be standing out like the president was coming. And they would just hug us, and some of ‘em were crying, and I thought, ‘My God, these are just quilts!’ … We had lived with these quilts a lifetime. They wasn’t art to us as (they were) to the people we were taking them to.

“It was almost unbelievable,” she remembered. “That’s when I had my first flight — to a museum in California. That’s the first time I got on a plane, and I’m telling you, that was something. I was kind of afraid when I got on there, but once that plane took off, I thought, ‘Well, I might as well settle down, cause I’m up here now, and they’re not gonna take me back.’”

She chuckled at the memory and continued. “It was joyous time. I had my first time to eat goat cheese on one of those trips. … A lot of those quilters didn’t like that goat cheese, but I liked that goat cheese, and I’d say, well give me your goat cheese!”

Claudia’s wish is that upcoming generations will find hope and success because of the struggles of the past and that they will continue the quilting heritage of Gee’s Bend. “We don’t want it to become a dying art. We want to continue to keep the quilting in the forefront of not just artists but quilters and everyday people. We (quilters) have to find like-minded people to know where that place is, and from there it grows.”

She is hopeful that soon, innovative and spontaneous quilting will take root in Pell City and St. Clair County.

Remembrance of past, hope for future

In their interviews, both Claudia and her Mom talked about Gee’s Bend’s isolation, poverty, struggle for survival, and the progress that had been made by the community’s determination and resourcefulness.

“Things are much better now,” Tinnie said. “Education is much better. We’ve got some very good kids that have grown up here — doctors, lawyers, nurses — that came from Gee’s Bend in spite of its beginnings.”

The post-slavery trials and tribulations of our African-American citizens in Wilcox County’s Gee’s Bend, with its injustice and inhumanity, echo in all of Alabama’s counties. A little delving into St. Clair County’s 19th Century estate records expose that inhumanity. However, the subtlety of injustice lies in the fact that it may fall upon anyone, regardless of race, color or belief.

But like those brilliant colors splashing through Gee’s Bend quilts, hope brightens the future. And this must be a determined hope for all.

Tinnie expressed it this way in a poem:

I’m not giving up in this life

Although there may be some strife

It may be sometime I have to wait

I know it’s never too late.

From this life I won’t retire

To be productive is a lifelong desire

I’ll go on, no, I won’t die

A new lease of life I have acquired

I feel now I’m more blessed

And I truly know I fear less

I also know I have to press

I want what I want and won’t settle for less

I will achieve, I see my goals

I won’t stop, no I won’t fold

Through the wind storm, rain or cold

To my faith and His hand I’ll continue to hold.

In this poem, Determined, from her book, Gee’s Bend Experience, Tinnie expresses hope, faith and determination. And in her quilts and daughter Claudia’s quilts, the careful observer can hear those three harmonies swirling in a crescendo of cloth and color to proclaim to the world Hallelujah! Amen! l

It was its stateliness as well as its history that attracted the current owners, James and Barbara Mask, to Bothwell-Embry-Campbell House. “She saw it in a real estate ad and had to have it,” James says. “She has filled it with antiques she bought at garage sales, flea markets and antique shops.” They’ve lived in the house since the spring of 2015.

It was its stateliness as well as its history that attracted the current owners, James and Barbara Mask, to Bothwell-Embry-Campbell House. “She saw it in a real estate ad and had to have it,” James says. “She has filled it with antiques she bought at garage sales, flea markets and antique shops.” They’ve lived in the house since the spring of 2015. “We reworked and repainted the second-level foyer, because the walls had been skinned with the constant moving of furniture up and down the stairs,” says James. They painted and papered most of the downstairs rooms in various colors and patterns, leaving the green woodwork alone. They haven’t made any structural changes.

“We reworked and repainted the second-level foyer, because the walls had been skinned with the constant moving of furniture up and down the stairs,” says James. They painted and papered most of the downstairs rooms in various colors and patterns, leaving the green woodwork alone. They haven’t made any structural changes.

Handed over the blueprints for success

Handed over the blueprints for success The award is given annually to a person who has gone above and beyond in their support of economic development in St. Clair County. “These are private citizens – not public officials – who are out there trying to make this county better,” said current St. Clair County Economic Development Council Executive Director Don Smith.

The award is given annually to a person who has gone above and beyond in their support of economic development in St. Clair County. “These are private citizens – not public officials – who are out there trying to make this county better,” said current St. Clair County Economic Development Council Executive Director Don Smith.

Story by Linda Long

Story by Linda Long “We offer something for just about everybody,” he said.

“We offer something for just about everybody,” he said. Moore agreed, saying Smith and City Manager Brian Muenger’s support for the project ensured its success. “Without their support and enthusiasm, this project would never have happened.” He added thanks to Funderburg as well.

Moore agreed, saying Smith and City Manager Brian Muenger’s support for the project ensured its success. “Without their support and enthusiasm, this project would never have happened.” He added thanks to Funderburg as well.

From hunting to climbing to cycling:

From hunting to climbing to cycling: More and more people are learning about the great kayaking and canoeing along Big Canoe Creek, a 50-plus-mile-long waterway snaking through St. Clair County and part of the Big Canoe Creek Watershed.

More and more people are learning about the great kayaking and canoeing along Big Canoe Creek, a 50-plus-mile-long waterway snaking through St. Clair County and part of the Big Canoe Creek Watershed.  Made up of rare combinations of sandstone with bands of iron throughout, the rock formations at Horse Pens 40 are tightly condensed and due to the uniqueness of the formation, provide a more challenging climbing experience. “A lot of places that people go to boulder you have to walk a quarter of a mile to get to the next climb, but here it’s all laid out back-to-back like it would be in a gym,” says Ashley Ensign, assistant manager at Horse Pens 40.

Made up of rare combinations of sandstone with bands of iron throughout, the rock formations at Horse Pens 40 are tightly condensed and due to the uniqueness of the formation, provide a more challenging climbing experience. “A lot of places that people go to boulder you have to walk a quarter of a mile to get to the next climb, but here it’s all laid out back-to-back like it would be in a gym,” says Ashley Ensign, assistant manager at Horse Pens 40.

“You’ll never find anybody who has put more love and consideration into a piece than I have,” said Foote, who has been carving wildlife – mostly birds – for 38 years. “You’re looking at somebody who no doubt loves what he does.”

“You’ll never find anybody who has put more love and consideration into a piece than I have,” said Foote, who has been carving wildlife – mostly birds – for 38 years. “You’re looking at somebody who no doubt loves what he does.” “My dad taught me a wonderful respect and reverence for wood,” Foote said, adding that he learned the different properties of wood make some types better for creating baskets and others best for making furniture. “He looked at wood like we look at different people.”

“My dad taught me a wonderful respect and reverence for wood,” Foote said, adding that he learned the different properties of wood make some types better for creating baskets and others best for making furniture. “He looked at wood like we look at different people.”