Helping meet the needs of everyone in St. Clair

Story by Jackie Walburn

Photos by Graham Hadley

A primary care clinic with a holistic approach, the Easterseals’ Community Health Clinic in Pell City, began and continues as a collaborative community effort to serve St. Clair adults without health insurance.

A year after its July 2018 opening, the volunteer-staffed clinic serves 380 patients and has logged more than 1,600 office visits. Located at 205 Edwin Holladay Place in downtown Pell City, the clinic shares building space with a Community Action agency, a mental health clinic and Christian Love Food pantry, agencies that help each other serve clients’ “mind, body and spirit.

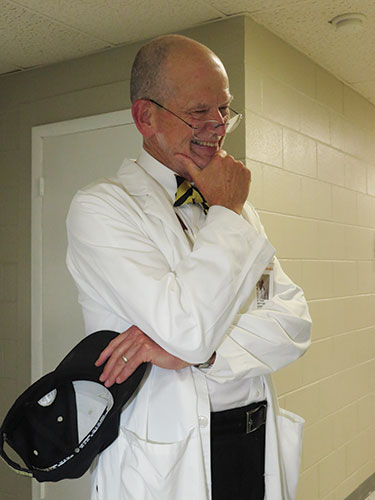

“Ten months after we got serious about it, we opened the doors to the clinic,” says David Higgins, executive director of Easterseals of Birmingham, which also operates a Pediatric Therapy clinic in Springville.

Because of the success of the Springville Pediatric Therapy clinic and the known need for services in St. Clair County, where some 12 percent of adults have no health insurance, the community clinic “seemed a logical next step as an Easterseals endeavor,” said Higgins.

He credits support and enthusiasm from Jefferson State Community College, Samford University and University of Alabama at Birmingham nursing programs, the town of Pell City, St. Vincent’s St. Clair Hospital – plus a long list of civic, church and community groups – for supporting the clinic.

Volunteers key

Volunteers, including three physicians and three nurse practitioners, staff the clinic, which is open from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Thursday. Two part-time administrators – Pam Thornburg, who manages the administrative front end of the clinic, and Letisha Crow, who administers the clinical end – were hired recently. “We have good volunteers, and we want to be respectful of their time,” Higgins says.

But volunteers – including Frances Burnete, Ruth Pope and the team of medical professionals who donate their time – remain key to day-to-day operations.

A belief in the need for the clinic prompted volunteer Burnete, who is retired after 50 years in the insurance business, to volunteer and keep volunteering at the clinic, where she is referred to as “Aunt Frances.” She says she feels “a kindness and understanding for the people who are our patients,” and believes in the work being done.

Volunteer and retired nurse Ruth Pope handles intake for new clinic patients. “This clinic was so needed,” she says, and now so appreciated. Encouraged to volunteer by friend and fellow volunteer Dr. Christy Daffron, department chair for the nursing program at Pell City’s Jefferson State Community College campus, Pope’s volunteer job is to sign up new patients.

The clinic charges $20 a visit for established patients and $30 for walk-ins, who are seen on Monday mornings. Patients are adults ages 19 to 64 without health insurance or Medicaid whose income falls within federal poverty level guidelines. Because Alabama is one of 14 states that have not expanded Medicaid, the state has a population of adults, many who work, who fall into a “coverage gap” and do not have health insurance coverage.

The doctor is in

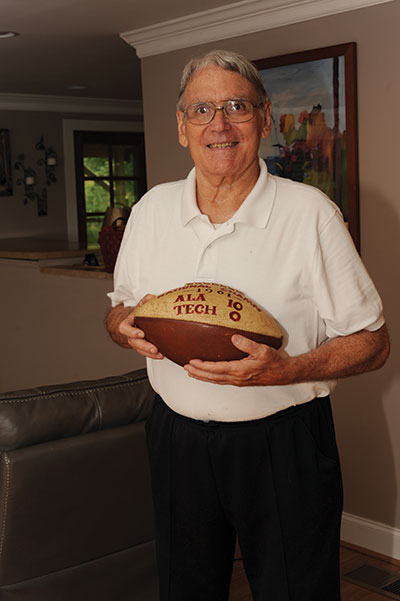

Pell City native Dr. James Tuck is one of three physicians who volunteer and regularly see patients at the clinic.

“The people we see are in desperate need of this service,” says Dr. Tuck, who grew up across the street from the clinic location. “It’s easy to see the need and the appreciation.”

Tuck’s family roots are in St. Clair County, and he has been in medical practice in his hometown for 36 years, now working with a local urgent care clinic. His first job out of medical school was in the current clinic building, he recalls, when the building housed the St. Clair County Health Department’s obstetrics clinic. “This is kind of bringing the past and present together for me.”

Mind, body and spirit

The clinic targets overall wellness with a holistic approach, Higgins says. “It’s primary medical care, but we look at root causes and what we can do to make life better for every patient,”

New patient intake includes a complete health assessment covering medical, social psychological, family, work, diet and living environment. “All these things help get a good handle on what’s going on with patients,” Higgins says, and may identify other needs patients have.

The clinic offers physical therapy, health and wellness education classes, chronic disease management for things like diabetes and COPD, as well as high blood pressure, and high cholesterol.

The clinic also works with a volunteer pharmacist, Elaine Hagler, who provides a discount list for many maintenance medicines, including access to insulin and other expensive maintenance medicines. While it helps patients find affordable maintenance medications, the clinic does not stock or prescribe controlled medications or narcotic painkillers.

Preventing disabling conditions

Easterseals, which celebrates its 100th anniversary this year, has always emphasized services to people with disabilities of all kinds. And, Higgins says holistic and preventative medical care through clinics like the one in Pell City can prevent medical conditions from becoming a debilitating disability.

“Some medical conditions, left undiagnosed or untreated, can result in complications that lead to disabilities,” says Higgins. Diabetes is a good example and is listed among conditions recognized by the ADA, the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act.

Untreated diabetes can affect all major organs and result in blindness, kidney problems and increased risk of stroke and heart attack.

“Diabetes is something that can be regulated, but keeping it regulated can be expensive,” Higgins notes.

“That’s where our patient assessments come in,” and where the clinic’s efforts to help patients with access to affordable maintenance medicine, including insulin, are making a difference in many patients’ lives.

Clinical training, too

Teaching is also a part of the clinic mission, as nursing and nurse practitioner students from colleges, including Jefferson State Community College and Jacksonville State University, volunteer and complete nursing clinical training at the clinic.

Higgins says it was conversations with Dr. Daffron at Jeff State and Debbie Duke, Congregational Health Program director at Samford University, both nurses and nursing professors, that helped spark the clinic’s formation. Providing healthcare in St. Clair County was something they wanted to do.

Both schools and others continue support. And, Project Access at the University of Alabama at Birmingham partners with the clinic when patients need referrals and appointments with specialists.

Coming together for worthy cause

As the clinic begins its second year in operation, Higgins says one of the most rewarding aspects of the new effort was “seeing how people came together to make change happen with a goal of being able to serve people who need help.”

A plaque listing the names of clinic founders and supporters is crowded with names of people and organizations that helped Easterseals Birmingham bring its first community health clinic to St. Clair County.

The list of 2018 Foundational donors “who believed in us when we were only a vision” includes: Area Health Education Center, Benjamin Moore Paints, Bill Hereford, City of Pell City, Cropwell Baptist Church, Dispensary of Hope, Empowered Church Health Outreach, H2H Golden Design, Hattie Lee’s, Home Depot, Jefferson State Community College, Jerry’s Carpet Service, Ken Knight, Morning Star Storage, Rick’s Custom Painting and Wallpaper, Room by Room, Samford University, Scotty Gray Flooring, St. Clair County Baptist Association, St. Vincent’s St. Clair, Susan Bush, UAB Project Access and Wally Bromberg Photography.

Perfect location prepped by volunteers

The clinic’s location in downtown Pell City, in a city-owned building, came about through “graciousness” and hard work by volunteers, says Higgins, a retired Moody police officer who lives in St. Clair County.

The worse-for-wear offices needed painting and new flooring, all provided by volunteers with donated supplies. The volunteer workers converted the offices into three exam rooms, several offices and a providers’ room and meeting area that the volunteer medical professionals use when needed.

With community resources just next door, the location proved perfect for the clinic with accessibility and a history as a former county health department site.

Easterseals: Taking On Disability Together

Clinic sponsor, Easterseals of the Birmingham area, is one of eight rehabilitation facilities owned and operated under the Easterseals Alabama, Inc, according to its website at eastersealsbham.org.

Easterseals has served metro Birmingham and the state since 1950 when the program Alacrafts began vocational training for disabled individuals. That program grew into the Spain Rehabilitation Facility near UAB that focused on physical medicine, rehabilitation research and education.

Higgins notes that the Pell City clinic is a first community clinic for Easterseals’ Birmingham area organization, and he hopes that it can be “a model to be replicated” elsewhere.

In addition to the new clinic, services offered and managed through Easterseals of the Birmingham area include:

Camp ASCCA, Alabama’s Special Camp for Children and Adults, a year-round camp on Lake Martin that offers rehabilitation and recreation for more than 7,000 people annually.

Two pediatric clinics – one in Pelham and the newest in Springville – providing speech, occupational and physical therapies, including early intervention, for patients up to 21 years old.

An adult program at the Birmingham headquarters on Beacon Parkway that provides evaluations, vocational training, job readiness and placement, computer skills training for adults, in addition to transition services for high school graduates.

A medical assistance grant program that helps individuals and families purchase medical equipment and make needed home modifications.

100 years of service

Nationally, Easterseals celebrates 100 years of service in 2019 and is America’s largest nonprofit health care organization, serving some 1.5 million people annually. In addition to serving children and adults living with disabilities, Easterseals also serves transitioning military disabled and other veterans since World War II.

Easterseals was founded in 1919 as the National Society for Crippled Children, the first organization of its kind. Founder Ohio businessman Edgar Allen, who lost a son in a streetcar accident and helped build a hospital in the child’s honor in his hometown, founded the organization to address the lack of services for children with disabilities who were then often hidden from public view.

An annual Easterseals fundraising campaign initiated by the society in 1934 introduced specially designed “Easter Seal” stamps that donors used on envelopes and letters. By 1967, the group’s work was so associated with Easterseals that the national society officially adopted Easterseals as its name. Today, the organization headquartered in Chicago with 69 affiliates nationwide.