Duff Morrison’s life a story of blessings, hard work and “The Bear”

Story by Paul South

Photos by Wallace Bromberg Jr.

Three words course through Duff Morrison’s 80 years: “lucky, fortunate, blessed.”

Chat with him, and clearly, he has been. A member of legendary Coach Paul “Bear” Bryant’s first Alabama team and first national championship team, Morrison excelled in engineering and business, working for some of American business’ best-known companies.

In his 50s, despite a body battered by his years as a multi-sport prep and college athlete, the Memphis native and St. Clair County resident was an internationally competitive racquetball player. Shoot, Duff Morrison was even a championship duck caller in Tennessee.

You name it, it seems, and Duff Morrison, the adopted son of Leonard Duff Morrison, one of the South’s most successful painting contractors, and a homemaker Mom, Bernice Turner Morrison, has done it – and done it well.

And no matter what he did, even today, the voices of his father, and of his “second Daddy” Bryant, echo in Morrison’s head and heart.

“My Daddy and Coach Bryant told me the same thing. ‘I don’t care what you do. But whatever you do, do it the best you can every time.’ That was the teaching that I grew up in.”

Three words course through Duff Morrison’s 80 years: “lucky, fortunate, blessed.”

Chat with him, and clearly, he has been. A member of legendary Coach Paul “Bear” Bryant’s first Alabama team and first national championship team, Morrison excelled in engineering and business, working for some of American business’ best-known companies.

In his 50s, despite a body battered by his years as a multi-sport prep and college athlete, the Memphis native and St. Clair County resident was an internationally competitive racquetball player. Shoot, Duff Morrison was even a championship duck caller in Tennessee.

You name it, it seems, and Duff Morrison, the adopted son of Leonard Duff Morrison, one of the South’s most successful painting contractors, and a homemaker Mom, Bernice Turner Morrison, has done it – and done it well.

And no matter what he did, even today, the voices of his father, and of his “second Daddy” Bryant, echo in Morrison’s head and heart.

“My Daddy and Coach Bryant told me the same thing. ‘I don’t care what you do. But whatever you do, do it the best you can every time.’ That was the teaching that I grew up in.”

Morrison followed the teaching to the letter, graduating from Treadwell High in Memphis at 16. He attracted the attention of college and pro scouts. The New York Yankees, New York baseball Giants and St. Louis Cardinals tried to hook Morrison with the lure of what then were considered big-money contracts. But Morrison – who neighbor kids called Duff Lujack after the Notre Dame great, Johnny Lujack – went to Alabama not only to play baseball and football, but to do more.

“I wanted to be an engineer,” Morrison says plainly.

A Drive to Excel

There’s a backstory here worth telling, a story Morrison didn’t hear until he was 38. His biological father was a Memphis police officer, and his birth mother was a Native American woman. The couple put the baby up for adoption.

Some folks may have been shaken by the news but not Morrison.

“There’s never been a luckier little boy than me,” he says.

Indeed, his father, who would employ more than 100 in a painting firm with clients from the Carolinas to Louisiana and his mother made sure their boy had a comfortable life. But he also learned the value of work and faith.

“On Saturdays, if I didn’t have a ball game, I was up and in the car by six in the morning going to work. I was baptized when I was 10, and my folks had me in church every Sunday.”

Things didn’t change at Alabama. Morrison was recruited to the Capstone by Coach J.B. “Ears” Whitworth, a good man, Morrison recalls, who never won at Alabama.

In 1958, a new coach with a new way of doing things, arrived in Tuscaloosa from Texas A&M. Alabama football would be forever transformed.

Marlin “Scooter” Dyess, an Alabama star who was also part of the same 1956 signing class as Morrison, recalls the impact of Bryant’s arrival. Dyess is now a Montgomery businessman.

“When he came in, it was like going from darkness into the light,” Dyess says. “When he came there, he pretty well established an attitude. As he told us one time, ‘I don’t want to ever hear about a past coaching regime. The problem with this program is sitting right here in this room. Those that stay will be part of rebuilding.’ He was absolutely right. He demanded respect and he got respect.”

Morrison recalls one of his first practices in the Bryant era. In the days before the NCAA restricted the number of players, some 300 were on the practice field for Alabama.

“Twenty-five boys quit that day,” Morrison recalls. “I went from 179 pounds to 163 that day. Coach Bryant tried to work you to death.”

“We thought he (Bryant) was crazy, trying to run everybody off,” Dyess said. “When we played LSU mine and Duff’s junior year, we only had 33 players because we had so many to quit. But he stuck to his plan, and it worked.”

Comparing Alabama’s fourth-quarter conditioning, Morrison described Alabama’s opponents by panting like a St. Bernard in a steam room.

“Every time that we played a ball game and got in the fourth quarter, the other team would be panting real hard. And we haven’t started to break a sweat. We were in better shape than anybody we ever played against. Coach Bryant worked your butt off.”

Like Dyess, Morrison never forgot that first meeting with Bryant, more than 60 years on.

“The very first meeting with Coach Bryant, he says, ‘Every time that ball moves on the football field, you do everything you can legally to help your team to win. Two, you go to every class and study as hard as you can because you’re not going to play football for the rest of your life. And number three, I don’t want any cheating in school, I don’t want any breaking rules or laws. If you can’t stand up to these things, get the hell out of here now.’

Keep in mind, the Crimson Tide’s previous three seasons were a collective nightmare, with a combined four wins from 1956-58, including a 40-0 loss to archrival Auburn in 1957.

But 1958 offered a glimpse of the glory to come for the Crimson Tide. Bryant’s first team beat 19th-ranked Mississippi State, defeated Georgia Tech and tied a ranked Vanderbilt team. Alabama almost upset Heisman winner Billy Cannon and LSU at Ladd Stadium in Mobile. In that game, a bleacher collapsed, injuring several fans.

Morrison had a big defensive play against the Bayou Bengals. Some remember it as an interception, others as a fumble plucked out of the air.

“Billy Cannon went around the right end and cut back,” Morrison remembers. “I hit that son of a gun so hard, that the ball flew up in the air, and I caught it at the 45 and ran back to the LSU 4.”

Dyess remembered the play as an interception that Morrison plucked from the air after it bounced off his helmet.

“We kidded Duff, that’d we had never seen anyone intercept a ball with his helmet. But it was a big play in the game. Duff is a great guy.”

Alabama would lose to the eventual national champs. But Dyess saw a change in the Tide that day.

“It was amazing,” Dyess recalls. “That’s what Coach Bryant turned around. We didn’t know we were no good. He made you feel like you were just as good as the team you were up against. In your mind, you sincerely believed that.”

And in 1959, Alabama, thanks in part to a sterling defensive effort by Morrison, the Tide upset Georgia Tech, 9-7. The previous Saturday, the Ramblin’ Wreck had upset nationally ranked Notre Dame in South Bend. Alabama was on the rise. Bryant called the ’59 squad his “turnaround team” that ended the season nationally ranked. The Tech game was pivotal.

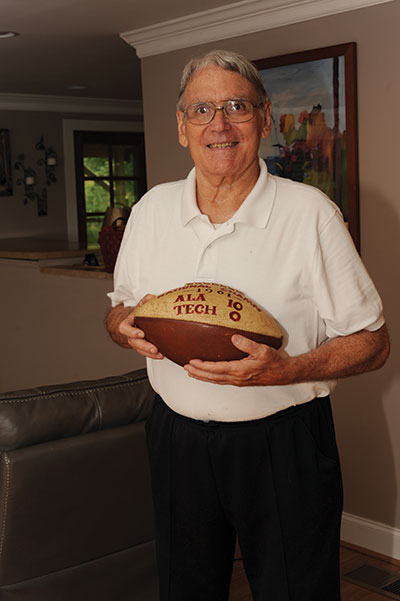

“I had nine tackles in the first quarter,” Morrison remembers. “Coach Bryant gave me the game ball. But somebody stole it from my dorm room after the game.”

Dyess says Morrison was an important part of the 1959 squad, playing both offense and defense.

“Duff was probably our best defensive back in the secondary. He was a guy who was a real leader. Nobody outworked him. Coach Bryant would take hard work over ability any day. Duff was an important cog in our ’58 and ’59 teams.

In an injury-plagued career, including a broken back in 1961, Morrison missed most of the national championship campaign in 1961. But Bryant never forgot the kid from Memphis.

“After we beat Georgia Tech in 1961, he gave me a game ball,” Morrison remembers. “He knew mine had been stolen. I still have the ball on my shelf.”

Bryant is never far away from Morrison. A treasured photo of the two, taken weeks before the legendary coach’s death in 1983, is prized. Morrison keeps extra copies of the photo to give to friends and fans who love to hear his stories.

But Bryant had an impact off the field as well. Morrison, juggling two sports as well as a demanding engineering course load, was having trouble in a course in the midst of baseball season. Worried, he called Bryant at home and explained his problem.

“He had a tutor in my room in 30 minutes,” Morrison recalls. “Hey, he cared about the ballplayers. He didn’t cheat. He wanted you to learn how to win and pay the price to win and do it the right way.”

He adds: “He felt like his job was to teach you to do the right thing in all aspects of life, not just on the football field.”

Morrison still holds the boys of Bryant’s first teams in his heart. Like Morrison, many went on to success in business, others in medicine and the law. While many have passed away, they are not forgotten.

“Those guys were about as good men as I’ve ever seen. It’s like you win World War II or something like that, and these were the members of your company. They went through all the battles and everything. I feel honored to have been with those boys.”

Dyess agrees. “There were some good people in that crowd, there really were.”

Of Morrison, one of his closest friends at Alabama, Dyess describes him as “one of those hard-working guys who was important to the team. He was a great teammate and friend.”

Off the Field

Morrison’s life after Alabama had its beginning in his last semester, when an advisor asked what he wanted to do after graduation.

“I want to be an engineer,” he says. “And I want to be the boss.”

The advisor directed him to Alabama’s School of Commerce. But engineering was always part of his professional life. In his first job, as a management trainee for American Brake Shoe, Co., he ascended to become a supervising engineer in less than a year.

He designed electronics plants for Emerson and poultry plants for Pillsbury. He was the top vacuum packaging salesman in the world for W.R. Grace for two years running and worked closely with companies like the Winn Dixie grocery chain and Bryan Foods.

“It was a grand life,” he says. “Two years in a row, that’s pretty good.”

He excelled in selling insurance, working for firms like Equitable Life. He also ran restaurants, like the Birmingham area mall locations of Sbarro’s Italian eateries.

While working full time during the day, he was a racquetball teaching pro at night. He helped design duck calls. And he supported and helped rear his family.

“I’ve had some real good jobs,” he says. “I got a good education and when you know the skills of engineering and management and you’re fair with people, and you do people right, they want to do good for you.”

If there is a dark cloud that lingers over Morrison’s blessed life, it’s the death of his son, Tim. Like his Dad, Tim Morrison played for Alabama, but was killed in a tragic auto accident in 2012. He was 44.

Duff Morrison calls his son’s passing, “the only bad thing” in his life. He holds fast to the belief that he will see his boy again.

“At least he didn’t suffer,” Morrison says.

Now at 80, Duff Morrison tries to stay busy, helping neighbors, building birdhouses, telling stories of Bryant and Alabama to anyone who will listen. He wrestles with aches and pains related to athletics and doesn’t go to games like he used to; stadium seats are too painful.

But he’s always quick to remind how fortunate his life has been. Many folks his age, he’s quick to remind, are in a wheelchair or shut in. As he looks back on life, gratitude flows. He looks forward to the day he will see his son again.

“God has played an important part in my life. I don’t take credit for any of this. I was blessed. Most people haven’t had the blessings I’ve had.”

As he would like to say, his years have been a grand time. He hopes he will be remembered for his dedication to doing a job well.

“I enjoyed it. I liked to work hard. My Daddy taught me a long time ago to do the job, do it right and work as hard as you can. If you’re going to go through life (halfway) doing stuff, why bother?”