Beatrice Muse Price:

Beatrice Muse Price:

Serving with the

Tuskegee Airmen

and breaking barriers

Story by Scottie Vickery

Photos by Wallace Bromberg Jr.

Submitted photos

As she looks back over photographs of her life and loved ones that hang in her room at the Col. Robert L. Howard State Veterans Home in Pell City, Beatrice Muse Price feels the need to pinch herself. “I’ve had a strange life with a lot of firsts,” she said. “It’s been an interesting, interesting journey.”

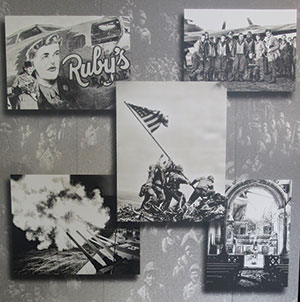

The granddaughter of slaves, young Beatrice started school at age 4 and never stopped blazing trails. The little girl with humble beginnings grew up to break color barriers in order to serve her country as a nurse during World War II. General George S. Patton was among her many patients, and she made history when she was assigned to help care for the Tuskegee Airmen, the first black pilots to serve in the U.S. military. “We took care of their medical needs and made sure they were in good shape,” she said. “Our job was to keep them flying.” In 2012, nearly 70 years after her service with the Airmen, she was presented the Congressional Gold Medal for her efforts in the war.

At 94, Price can’t think of much she would change about her life. After leaving the Army, she was a nurse at the Birmingham VA Medical Center and started a health and wellness program at her church, which she counts among her greatest accomplishments. Despite growing up during the height of segregation she lived to see Barack Obama become the first African-American president and was among the estimated 1.8 million who flocked to Washington for his inauguration in 2009. Four years later, she was the special guest of U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell during President Obama’s 2013 State of the Union Address.

“Every time I turn around, I’m involved with something that’s made me think, ‘Can you imagine this?’ I’ve never seen any reason to stop with less than you were capable of doing. Now that I look back on it, I can’t remember anything I was afraid to do, and I think that’s why I had such great opportunities everywhere I went,” she said.

“Every time I turn around, I’m involved with something that’s made me think, ‘Can you imagine this?’ I’ve never seen any reason to stop with less than you were capable of doing. Now that I look back on it, I can’t remember anything I was afraid to do, and I think that’s why I had such great opportunities everywhere I went,” she said.

Price was born in Bessemer on Jan. 21, 1924, the second of Henry and Frances Muse’s six children. The family moved to Hale County when she was 3, and she grew up on a farm in Greensboro, where her parents modeled strength, courage and determination. Badly injured in World War I, her father was in and out of the VA hospital for much of her childhood. “Mama had to run the farm, and boy did she run it,” she said. “She believed in doing everything possible to make life better for all of us.”

For that reason, Price got an early start on her education “My sister Ruth, who was 11 months older, was afraid of everything, including her shadow,” she mused. “When she went to school, Mama started me too, even though I was only 4, just to be company for her.”

Price excelled in school, despite her many chores around the farm and the time she spent helping to care for her father. That experience is ultimately what set her on her career path. “My father always said, ‘Bea, you would make a good nurse.’ He told me that from the time I was 3. By the time I graduated high school, he had convinced me totally,” she said.

The problem was, she graduated early, at age 16. “You had to be 17 to go to nursing school, so Daddy got a birth affidavit for me. Because of midwives, a lot of people didn’t have birth certificates, so rather than have me sit out a year, he aged me a year on my birth affidavit,” she said.

Despite never having left Alabama, she boarded a train by herself and went to the Grady Memorial School of Nursing in Atlanta, graduating three years later in 1944 as a registered nurse.

Despite never having left Alabama, she boarded a train by herself and went to the Grady Memorial School of Nursing in Atlanta, graduating three years later in 1944 as a registered nurse.

During her college days, “segregation was at its height,” she said, and she remembers the superintendent of nurses telling her and her classmates to “go back to the cornfields and cook kitchens where you belong.” The white students and black students were separated, but Price didn’t allow the racism she experienced to affect her focus. She graduated with one of the highest grade point averages among both groups of students.

By the time she finished nursing school, “they were appealing for Army nurses with every breath,” she said. “We had recruiters at school every week or so, but you had to be 21 to join the Army. Daddy got a birth affidavit for college, but he said he wasn’t going to mess with the military.”

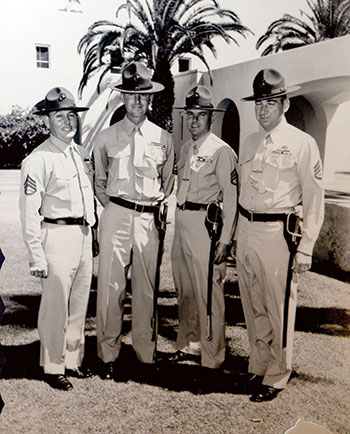

Instead, she spent a year in Trinity Hospital, an all-black private hospital in Detroit before becoming a U.S. Army Nurse in 1945. She joined the Army three days after turning 21 and was one of 12 black nurses sent to work at a hospital in Fort Devens, Mass., after completing basic training. “We were the first black nurses there and when they took us to breakfast the next morning, the forks were hitting the plates so hard we were looking to see how much china was broken,” she said with a laugh.

After earning the respect of her colleagues, she was the first black nurse to be promoted to head nurse at the hospital. Although she can’t remember what he was treated for, Gen. Patton was a patient in her ward. “Everyone called him ‘Blood and Guts’ because he was so forceful and fearless,” she said, adding that he wasn’t difficult or intimidating during his stay. “He disappointed me,” she joked.

After being promoted to First Lieutenant, Price was stationed at Lockbourne Army Air Base in Columbus, Ohio, and was assigned to the Tuskegee Airmen. The pilots, who trained in Alabama as a segregated unit at Tuskegee Institute’s Motion Field, were subjected to discrimination both inside and outside the military. “They were trying to be the best they could be in spite of the fact that people didn’t want them to do it at all,” she said. “I enjoyed working with them to the highest.”

Price said she got to know some of the pilots and flew with them on a few practice flights, even taking the controls on occasion. “They had to keep their hours up and they were so happy to have company along, they taught you everything they knew. Maybe I shouldn’t be telling you that,” she said with a grin.

After the war ended and Price returned home, she continued her nursing career at the Birmingham VA Medical Center, where she worked for 34 years. She was married twice and has three children, two stepchildren, four grandchildren, five step-grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Through the years, she’s “adopted” some others and counts them as her own. She credits her family and her career among her greatest blessings.

After the war ended and Price returned home, she continued her nursing career at the Birmingham VA Medical Center, where she worked for 34 years. She was married twice and has three children, two stepchildren, four grandchildren, five step-grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Through the years, she’s “adopted” some others and counts them as her own. She credits her family and her career among her greatest blessings.

Price rejoiced in 2007 when President George W. Bush presented the Tuskegee Airmen – which included the nearly 1,000 pilots and support personnel such as armorers, engineers, navigators, intelligence officers, weather officers and nurses – with the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest honor given by Congress. In 2012, U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell presented Price with her own medal during a ceremony at her church, Sixth Avenue Baptist.

She is amazed at the honors she has received for what she calls fulfilling her calling.

“There’s nothing in the world I could have enjoyed more than nursing,” she said. “It has really been the most rewarding career I could possibly imagine. I’ve had a rich, full life, and I’ve just been in the right place at the right time with the right things somebody was looking for. It’s how God works. He finds you and gives you assignments, and you’ve just got to try to carry them out.”

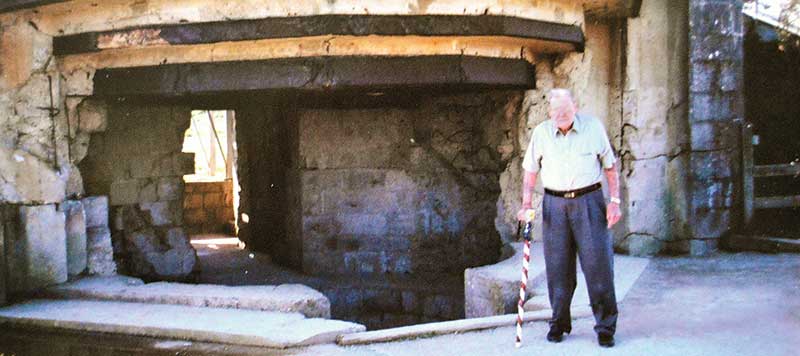

Tales of survival from Omaha Beach

Tales of survival from Omaha Beach “Because the weather was so bad that week,” Hilman explains, (German Field Marshal) Rommel had left the area to attend his wife’s birthday party, thinking we couldn’t land with that kind of weather. The Germans needed aggressive field leadership, and with Rommel gone, they were left without.”

“Because the weather was so bad that week,” Hilman explains, (German Field Marshal) Rommel had left the area to attend his wife’s birthday party, thinking we couldn’t land with that kind of weather. The Germans needed aggressive field leadership, and with Rommel gone, they were left without.”

He spoke of his bombing mission to Berlin a month earlier – on May 7 and May 8. “On May 8, we turned around and went back to Berlin and bombed it again. You can’t imagine the devastation.”

He spoke of his bombing mission to Berlin a month earlier – on May 7 and May 8. “On May 8, we turned around and went back to Berlin and bombed it again. You can’t imagine the devastation.”

But short of talking walls and such, Discover writers and photographers visited the veterans home just weeks before its fifth anniversary in Pell City to record those stories. The 254-veteran capacity home is full now, and stories abound from different wars, different perspectives and different walks of life. The common thread of this band of brothers and sisters is service to country first.

But short of talking walls and such, Discover writers and photographers visited the veterans home just weeks before its fifth anniversary in Pell City to record those stories. The 254-veteran capacity home is full now, and stories abound from different wars, different perspectives and different walks of life. The common thread of this band of brothers and sisters is service to country first.

He was the son of farmers in Attalla and joined the service after high school. His method of carrying messages without getting hurt? “I’d go one time to the left and two times to the right. Then I’m hitting the deck. They’re shooting at me.”

He was the son of farmers in Attalla and joined the service after high school. His method of carrying messages without getting hurt? “I’d go one time to the left and two times to the right. Then I’m hitting the deck. They’re shooting at me.”