Chandler Mountain: The tomato capital of Alabama

Story Leigh Pritchett

Photos by Michael Callahan

Two pieces of white bread glazed with mayonnaise. Slices of a fat, juicy, vine-ripened tomato still warm from the sun. A sprinkling of salt and pepper.

A good ole tomato sandwich is a summertime delicacy.

And St. Clair County’s Chandler Mountain just happens to be known near and far as the place to get tomatoes.

Alabama Farmers Federation, in a 2007 publication, calls Chandler Mountain “The Tomato Capital of Alabama” because truckloads are transported from there on a daily basis during the months of harvest.*

In fact, “Alabama ranks … 12th in (production of) fresh-market tomatoes,” notes another federation publication.*

St. Clair County leads the state in vegetable and melon production, reveals a 2013 report of the Alabama Cooperative Extension System and Alabama Agribusiness Council.*

Those statistics are not difficult to believe when considering that Smith Tomato, LLC – just one of a number of tomato farms on Chandler Mountain – annually cultivates 100 acres, producing about 200,000 boxes of tomatoes. Each box contains between 25 and 30 pounds of tomatoes. That amounts to at least five-million pounds of tomatoes a year from a single farm.

Those statistics are not difficult to believe when considering that Smith Tomato, LLC – just one of a number of tomato farms on Chandler Mountain – annually cultivates 100 acres, producing about 200,000 boxes of tomatoes. Each box contains between 25 and 30 pounds of tomatoes. That amounts to at least five-million pounds of tomatoes a year from a single farm.

Chad Smith – the 26-year-old farmer who runs Smith Tomato with his brother, Phillip, and father, Leroy — said their tomatoes are shipped to wholesalers within a 15-hour driving radius. The tomatoes travel as far as Miami, Fla.; Washington, D.C., and Dallas, Texas.

Smith said their Mountain Fresh, Roma, yellow, grape and cherry tomatoes end up in restaurants, stores and large farmer’s markets.

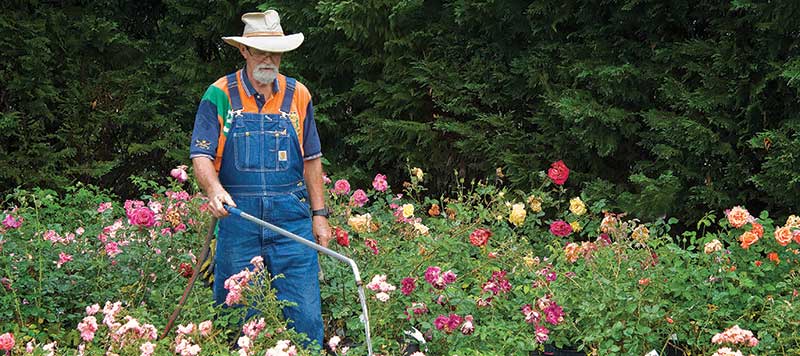

Not far from Smith Tomato is Rogers Farm, operated by Dwight Rogers.

Rogers, a tomato farmer for nearly five decades, sows approximately 15 acres of them each year. Among the kinds he offers this year are Mountain Fresh, Florida 47 and grape tomatoes.

A “truck farmer,” Rogers grows peanuts, peppers, squash, cucumbers, corn, pole beans and cantaloupe on another 15 acres of his farm.

Tomatoes, though, constitute 70 percent of his business, he said.

Rogers’ tomatoes and other produce are sold at his shed and through a farmers’ market in Birmingham. From the farmer’s market, Rogers’ tomatoes ultimately end up in produce stands all over North Alabama, he said.

Tomatoes’ paradise found

Chandler Mountain is situated in northern St. Clair near Ashville and Steele.

“(It) is quite unlike any other in the Appalachian Range,” explains Mattie Lou Teague Crow in her book History of St. Clair County (Alabama). “It is a small, rock-rimmed, boat-shaped mountain, 1500 feet above sea level, and it is approximately seven miles long and one and a half miles wide. Its summit is a plateau of silky loam which grows tomatoes and beans to perfection.”*

Mike Reeves, regional extension agent in commercial horticulture for Alabama Cooperative Extension System, said Chandler Mountain offers farmers good soil, an ample water supply and the advantages of elevation. Because of elevation, there are fewer incidents of frost on the mountain than in the valley. That permits farmers to plant earlier in the spring and harvest later into the fall.

Jamie Burton, who retired after more than 60 years of growing tomatoes, said the altitude promotes cooler temperatures.

“In hot summertime, it is about five degrees cooler on the mountain” than in the valley, said Burton, who cultivated 75-100 acres in tomatoes on Burton Farm. Tomatoes, he continued, do not fare as well in temperatures greater than 95 degrees.

Rogers said air circulation on the mountain also benefits tomatoes.

“Feel the breeze,” Rogers said. “We have a breeze almost all the time.”

That, he said, helps to keep the tomato vines dry.

A way of life

The tomato farmer does the bulk of his work in 10 months each year, but gets paid during the four months of harvesting and selling, said Smith.

The days spent preparing, sowing and reaping, though, are frequently quite long, Smith said. A farmer might work more than 10 hours during daylight and then commence spraying after dark when it is better for the plants. Before the night ends, he may be loading a wholesale truck until 1 a.m. Four hours later, he is back in a field spraying until sunrise.

Rogers said there are times when he is up at 2:30 a.m. to get his tomatoes to market in Birmingham and may not finish his day of farming until 10 or 11 p.m.

Added to the long hours are other necessary aspects of the business, such as USDA inspections and new regulations to learn and follow, Smith said.

During the growing season, a tomato farmer really cannot take a vacation because of all that must be done, Burton said.

Nonetheless, “You don’t get bored of it,” Smith responded. “You get to do a little bit of everything.”

The growing season spans from April until the first frost (generally October). During that time, 50,000 to 80,000 tomato plants are sown every three weeks on the Smith farm. There are a total of seven planting cycles or “settings.” This staggered schedule produces a crop of mature tomatoes almost constantly.

“Most of the time, we can plant (a setting) in a day,” Smith said.

However, staking the plants in order to tie them and hold them upright takes longer.

“That, right there, really is work,” Smith said.

In a day’s time, it is possible to stake about 40,000 plants — or 10 acres, he said.

The cost to sow 100 acres — including expenses for plants, equipment, supplies and labor – would be at least $1 million, Smith said.

Because of all the time, effort and financial resources required to be a tomato farmer, Smith said a person has to be completely devoted to it. It has to become “a way of life. You’ve got to have the will to want to do it.”

Added Esther Smith, his wife, “Then, you pray you come out (well) in the end.”

One hailstorm, Chad Smith said, could doom a whole crop.

“Weather’s the biggest factor” that the farmers face, Smith said. “The next biggest thing is the market.”

Market prices for tomatoes fluctuate frequently, which means farmers could experience either “feast or famine” at harvest, Reeves said.

Last year, for example, the market price was low much of the season.

Smith said 85 percent of the tomatoes reaped on his farm last year brought a price that was either below cost or at cost. As the last 15 percent was being harvested, the market price rose significantly, which balanced the equation.

A changing legacy

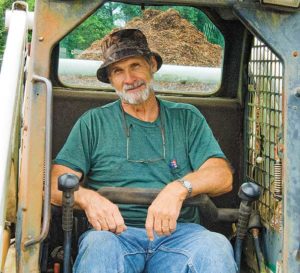

Eighty-six-year-old Hoover Rogers of Chandler Mountain retired from tomato farming only four years ago.

He farmed for years and years, even while he was an educator and principal.

He farmed for years and years, even while he was an educator and principal.

“It was hard work,” Rogers said, “but it was enjoyable.”

He said he has seen many changes occur in the science of producing tomatoes — from cultivating with mules to using tractors, from dealing with drought conditions to providing irrigation, from sowing on the ground to planting on raised, plastic-covered rows.

“The way of fertilizing, the way of spraying has really changed the last 15 years,” added Dwight Rogers, Hoover’s nephew.

Even the number and size of the farms have changed. Burton said there were more farms when he began tomato farming. Although fewer in number now, the farms tend to be larger.

Smith explained that the current method of planting on raised, plastic-covered rows is called “plasticulture.”

Creating “plasticulture” rows is done with a special attachment for a tractor. That attachment gathers soil into raised rows, lays irrigation line and spreads plastic over the rows, while directing more soil onto the edges of the plastic to secure it. All these tasks are done simultaneously.

Then, another tractor attachment punches holes through the plastic and into the soil. Finally, a tomato plant is placed by hand into each hole.

Smith said the plastic inhibits weed growth, holds moisture close to the roots and keeps the plants off the soil, which decreases the risk of disease and damage.

Yes, tomato farming requires an enormous amount of work. But “when this gets in your blood, you like it,” Dwight Rogers said. “Just the smell of the dirt when you start tilling the ground” keeps him farming year after year.

Tomato farming on Chandler Mountain has a legacy of being a family tradition. Hoover and Dwight Rogers’ family, for instance, has been farming the same land more than 100 years.

This past summer saw three generations working at Smith Tomato.

“Now, we’re getting grandkids involved in it,” said Kathy Smith, Chad’s mother.

Kista Lowe was reared in the tomato farming business like her brother, Chad Smith. As an adult, Lowe worked elsewhere for 15 years.

Yet, her heart kept recalling the excitement she felt when heavy picking commenced and all those boxes of tomatoes started arriving at the packinghouse. She missed it so much that she returned to the business three years ago.

Esther Smith understands why that would be the case. She grew up in tomato farming in Florida and enjoys everything about the process. “You look forward to it in the winter.”

Although Burton retired from tomato farming 10 years ago, and the farm responsibilities have passed to subsequent generations, the desire has not subsided.

Even now, Burton still gets the urge to go out and grow tomatoes.

A tasty attraction

Growing tomatoes for wholesale distribution is certainly a major part of Smith Tomato’s business. Yet, the farm is actually a multifaceted undertaking.

While wholesale shipping is being handled at one end of the farm’s packinghouse, there is laughter and lively conversation in the tidy produce stand at the other end.

Seven days a week from July to October, Kathy and Esther Smith and Kista Lowe can be found at the produce stand, which is open to everyone.

In addition to tomatoes, peppers and cucumbers grown on the Smith farm, the stand sells produce from neighboring farms.

The three ladies spend their days handling phone calls and attending to customers from many counties and numerous states.

“They’re either coming or calling all day long,” Kathy Smith said of the patrons.

Some are new customers and some have come back year after year.

On one August morning, H.J. Hamilton of Sylacauga explained why he travels to Chandler Mountain to get tomatoes. “I come up here because they have such fine tomatoes and such friendly people.”

Robert Bowman of Hiram, Ga., said he has been purchasing from Smith Tomato for years. This was his second buying trip in a week.

It was the first visit for Glenda Karr of Ashland, and she liked what she saw.

A relative’s comments about Smith Tomato had awakened the interest of Eunice Bowden of Anniston, and she had to check it out.

James Campbell of Argo had the bed of his truck loaded with tomatoes that he and others in his group had gathered from one of the fields.

“They’re the sweetest tomatoes I’ve ever tasted,” Campbell said.

For about 15 years, Campbell has gone there to take advantage of “u-pick,” which is Smith Tomato’s invitation for people to gather tomatoes for themselves. The cost to do so is nominal.

“All our fields get turned out to the public to pick their own when (we) get finished shipping them,” said Kathy Smith.

“U-pick,” for some customers, is a fun activity and is treated almost like a vacation. It is not unusual for individuals to drive as many as three hours for the chance to glean because they enjoy going into the fields so much, Chad Smith said.

For those who may have limited financial resources, it is an opportunity to get fresh produce for a small amount of money, Lowe said.

Then, there are people who minister through “u-pick.”

Kathy Smith said missionary groups gather the tomatoes to help feed people in need.

And after they finish gleaning, group members seek blessings for the farm.

“They pray over our fields for a good crop next season,” Lowe said.

For more information about Smith Tomato, LLC, visit its Facebook page or call 256-538-3116. Dwight Rogers may be reached at 256-490-4535.

*Information used with permission.

The two had admired the farm from the time they were lads.

The two had admired the farm from the time they were lads. “It would have taken us 10 years to breed up to the kind of animals we bought off the bat,” Joey said. “… We bought our way into the (cattle) business as big as we could, and tomato farming allowed us to do that.”

“It would have taken us 10 years to breed up to the kind of animals we bought off the bat,” Joey said. “… We bought our way into the (cattle) business as big as we could, and tomato farming allowed us to do that.”

St. Clair County style food

St. Clair County style food “Come in every Saturday mornings from 9am-11am and hear piano hymns, Celtic, classic and bluegrass by Matthew Bailey,” Sarah Jane says, speaking about her brother. “If you would like to bring an instrument, we would love to have them. All musicians get a free breakfast sandwich and coffee.”

“Come in every Saturday mornings from 9am-11am and hear piano hymns, Celtic, classic and bluegrass by Matthew Bailey,” Sarah Jane says, speaking about her brother. “If you would like to bring an instrument, we would love to have them. All musicians get a free breakfast sandwich and coffee.”

Sheep-shearing, cheese tasting at Alabama’s only sheep dairy

Sheep-shearing, cheese tasting at Alabama’s only sheep dairy Eager volunteers hung on the door of the shearing stall, ready to grab their share of fleece. They laid it on a piece of wide-web pasture fencing stretched between two metal saw horses, where they picked out debris. A large pile accumulated beneath the makeshift “screen” as dirty pieces dropped through the holes. The good stuff was packed into garbage bags to be taken home, washed, carded and spun or woven.

Eager volunteers hung on the door of the shearing stall, ready to grab their share of fleece. They laid it on a piece of wide-web pasture fencing stretched between two metal saw horses, where they picked out debris. A large pile accumulated beneath the makeshift “screen” as dirty pieces dropped through the holes. The good stuff was packed into garbage bags to be taken home, washed, carded and spun or woven. There was already lots of good goat cheese being made here in Alabama, according to Ana, and cows were too big a leap. “Sheep are docile creatures,” Greg said. “They don’t smell, either. Sheep produce less milk than goats or cows, but its milder and richer.”

There was already lots of good goat cheese being made here in Alabama, according to Ana, and cows were too big a leap. “Sheep are docile creatures,” Greg said. “They don’t smell, either. Sheep produce less milk than goats or cows, but its milder and richer.”