St. Clair Springs log homes

Story by Elaine Hobson Miller

Story by Elaine Hobson Miller

Photos by Jerry Martin

More than 100 years ago, the Jones Road homes of Mike and Cathy Harris and Jimmy Calvert on Jones Road began as simple, four-room log cabins. They were part of the same piece of property, the latter housing the servants’ quarters for the former. Additions and renovations have saved these relics of the past from the ravages of time and neglect, while the personal touches of current and former owners have turned them into modern-day cottages that retain much of their rusticity.

“It feels like half my house is old, half is new, but we don’t know when each was built,” says Cathy Harris, who moved here with husband, Mike, in June 2012 from Raleigh, N.C.

That description fits both the Harris home and the Calvert home. The split personality of the houses is more evident in the Harris home, however, especially from the outside. A stone facade covers the newer half, while the log section, with its tan chinking, dominates the other. Where the two are joined inside, exposed logs remind the owners of the house’s humble beginnings.

“Every floor in this house is (made of) a different kind of wood,” says Cathy Harris. “I think every owner put his own stamp on this house.”

Their stamp happens to be a combination of rustic furnishings from a mountain cabin they used to own and from their Raleigh residence. In the dining area, a faux antler chandelier hangs over a huge round table that belonged to Cathy’s mother. The table is topped by a twig basket on a large lazy Susan, and is surrounded by old hickory chairs.

“I’d rather be outside than inside, so everything is decorated outdoorsy,” Cathy explains as she leads a tour of the house. The master bedroom has prints of green ferns, either elk or deer antlers (she’s not sure which) hanging over the bed, with a rustic wooden bench at its foot. The Great Room has leather sofas and a long, low, wooden coffee table. Coming out of the kitchen on the opposite side of the dining room, the original log section of the house begins. “I call this my living room because it’s a little more formal than the Great Room,” Cathy says.

A stone fireplace and a red front door dominate the room, but the deer head over the fireplace, like the antlers throughout, was purchased, not shot. “We don’t hunt,” Cathy says. “I bought that deer head at an antique store for $40.” More antlers, prints of dogs and horses, a rustic wooden coffee and an end table share space with a Persian rug. A sheep-horn lamp from the old Rich’s store in Atlanta is draped with the halters the grown Harris children used with their childhood ponies. More antlers adorn the walls and built-in bookcases in this room.

But the most striking feature of the living room is the wooden catwalk high above. Steep log steps lead up to the catwalk, which has a small loft at each end that the Harrises use for storage. Arthur Weeks, the late Birmingham artist who owned the original L-shaped house in the 1980s, used both areas as bedrooms, even though their peaks only allow standing room in their centers. It was Weeks who added the skylight that brightens the room, but the catwalk and lofts are original to the house.

Off one side of the living room is a small area with a log ceiling that Mike uses as his office, while off the other side are two small bedrooms and two bathrooms. The ceilings are low and the floors are sloping in these rooms, but a structural engineer pronounced the house safe. The sloping is due to settling. These bedrooms were carpeted and decorated by the former owner, who painted the log walls in one of them. “I don’t know what’s under the carpet,” Cathy confesses.

The Harrises have done no remodeling inside the home, other than painting some of the rooms and adding granite countertops in the kitchen. Outside, however, they literally hit the ground running from the moment they arrived.

The Harrises have done no remodeling inside the home, other than painting some of the rooms and adding granite countertops in the kitchen. Outside, however, they literally hit the ground running from the moment they arrived.

Their first project was to take down a huge tree house in the backyard and their pond’s boat house that was falling in. Most of the gardens were put in by Weeks, but they put up new fencing, limbed some trees, planted grass and cleaned up outside. Next, they screened in the open porch at the rear and built a pool equipment house. The swimming pool was already there. A real working well sits unused in a side yard.

“When the weather is nice, we live on the screened porch,” says Cathy. “We need to put a TV out there, we use it so much.”

Arthur Weeks disassembled a small log barn that was behind what is now Jimmy Calvert’s house, just up the road, then reassembled it to one side of the house and used it as his studio. Now a small, two-level apartment rented by Jimbo Bowers, the former barn also has a shed roof that shields lawn equipment from the elements.

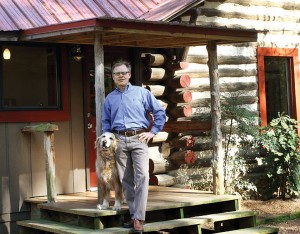

Jimmy Calvert says the original 800-square-foot log portion of his 2,900 square-foot house probably was built in the late 1800s, while the two-story cottage-style addition was built by former owners Donnie Joe and Kim Kirkland in 1998-99. The four-room log cabin has three fireplaces around one central chimney, a common arrangement for the time in which it was built.

“It was an emotional buy,” Calvert says about his purchase.

An attorney with an office in Birmingham and Springville, he moved from Birmingham in 2004. His master bedroom was in the original log cabin while renovating the addition, which now has his living room, master bedroom and bath downstairs, two bedrooms and a bath upstairs. He has spent six figures over the course of eight years, and most of his free time during 2009 and 2010, restoring the place.

“There’s not an inch of this place that I haven’t restored,” Calvert says.

With the help of a friend, Walker Peerson, who was experienced in home construction and renovation, Calvert ripped out the floors down to the dirt in the original kitchen and dining room. That’s when he discovered that the logs underneath were laid out in a hub-and-spoke fashion, with the fireplace as the hub. He had to replace many of the floor joists and put down new heart pine floors. He removed the tile covering all the stone fireplaces and rebuilt the hearths. He tore out all the replacement windows and rebuilt their frames, putting plate glass in several rooms while keeping the one window that was original to the house. It’s now in his home office. He re-wired and re-plumbed the log cabin, too.

“A lot of the chinking was coming out, so I scraped out those places and re-caulked them, using a product called Perma-Chink,” Calvert says. “Then I painted the chinking an antique white.”

He removed the walls of the hallway between what was the original kitchen and a bedroom in the log section, then built a modern kitchen with pine countertops and stainless-steel appliances in the former bedroom. He and Peerson then built a 3-foot by 6-foot picture window at one end, overlooking the backyard. The original kitchen is now his dining room. His home office is in what used to be a second log bedroom.

“I’m 80 percent done with what I want to do here,” Calvert says. “What’s left is cosmetic, little things like knobs on the kitchen cabinets.”

“I’m 80 percent done with what I want to do here,” Calvert says. “What’s left is cosmetic, little things like knobs on the kitchen cabinets.”

He also rebuilt an old skinning shed outside, turning it into an air conditioned workshop and dog house for his two dogs. A 350-year-old oak tree lends shade to the screened porch on the front of the house. The concrete floor of the porch is patchy, but Calvert plans to leave it that way to maintain its rustic appearance. He also built a new deck on the back of the house and took down some old, dilapidated chicken houses.

Calvert has been told that the cabin was re-chinked in 1937 using mud from the pond behind his house. Initials and a date that were written in the chinking on one side of the house prove that point.

“Jones Road was the original road from Springville to Ashville,” Calvert says. “You came up Highway 11, and right onto Jones Springs Road. Then they built I-59 and cut off this road, which now dead ends next to my property. Alabama 23 now goes over I-59 from Springville to St. Clair Springs and up to Ashville.”