Top Photo: Keith Little Badger, Cherokee tribe of Northeast Alabama, surveys area

Story by Mackenzie Free and Carol Pappas

Photos by Mackenzie Free

Charlie Abercrombie has a history on this mountain, dating all the way back to the War of 1812 and a man by the name of Chandler.

That’s why today’s fight to save it meant so much to so many. For Charlie, it was personal.

Many joined the fight along the way and for varying reasons – from newcomers to old timers. It was personal to them, too.

Mackenzie Free, a photographer for Discover Magazine, joined the effort and was a vocal advocate in the Save Chandler Mountain movement. She lives in the mountain’s valley on the same land her husband’s family raised generations. Mackenzie and her family stood to lose it all – just like Charlie – if Alabama Power’s quest to build a hydro dam there succeeded.

It didn’t.

This is but one story among many, painting the picture of how history could be lost so easily. Here are excerpts from Charlie’s story that Mackenzie shared on social media at the height of the fight to save the mountain:

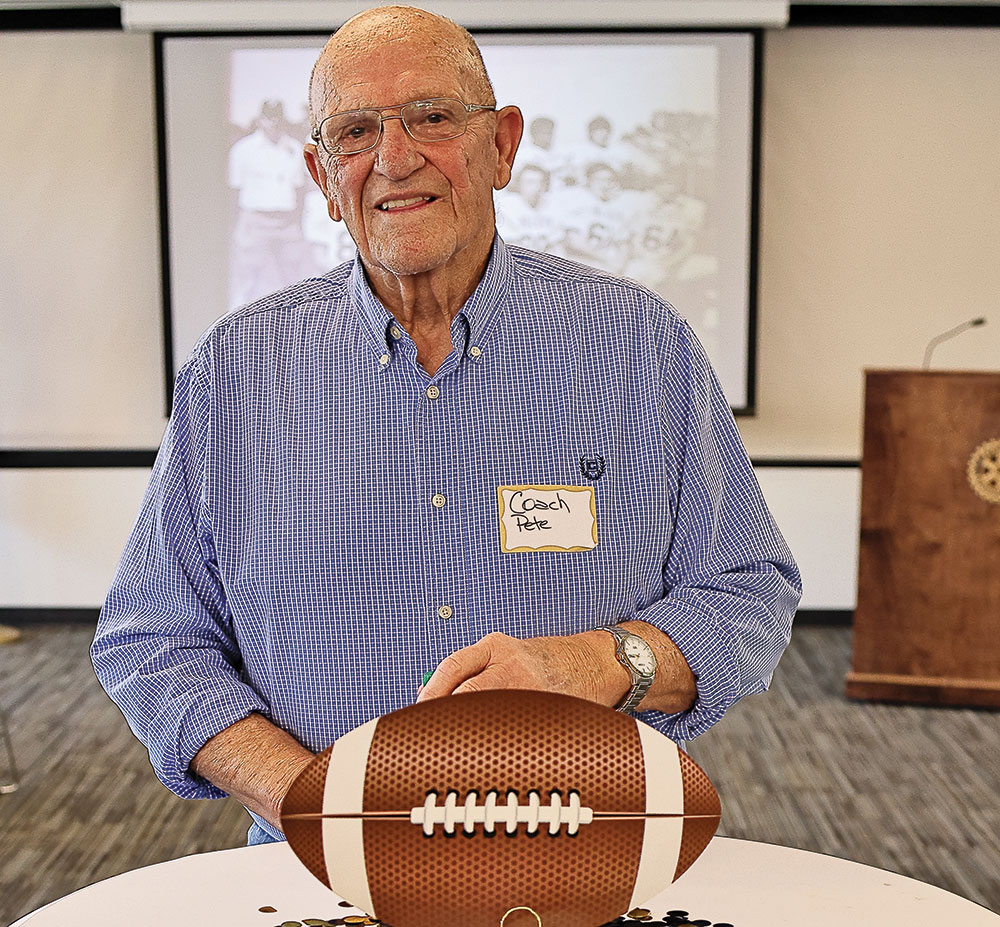

This is Charlie Abercrombie.

Out of all the folks I’ve met since moving out to the Steele/Chandler Mountain area 10 years ago, he might very well be one of my favorites.

I “think” he said he’s 77 years old, but I might be mistaken because he’s far too sprightly and agile for that to be correct.

He’s very charming and intelligent and has a memory that far exceeds mine.

He is also humble, hardworking and takes a lot of pride in his land.

You see, this land he calls home is special.

Very special …

His property was part of a presidential land grant from the U.S. government to Mr. Joel Chandler (yes, Chandler… as in ‘Chandler Mountain’) for fighting along with Andrew Jackson in the war of 1812.

A short while later, in the early 1840s, a grist mill (grinding wheat to flour and corn to meal) was built here. It was powered by water… this dam and Little Canoe Creek.

Mr. Abercrombie’s great grandfather later purchased this property and grist mill from the daughter of Joel Chandler in 1896. Let me reiterate that … 1896!!

(*To put that in perspective this property has been in his family longer than Oklahoma, New Mexico, Arizona, Alaska, and Hawaii, have been a part of the United States!!!)

This land is more than just his home… its history!

It’s his heritage.

It’s sewn into the very fiber of who he is.

It’s his legacy.

And you’ll find that is a common theme for most of these families (mine included) that stand to lose everything their forefathers fought so hard to protect.

It’s more than land … it’s bigger than that.

It’s not money either … it’s about history, heritage and the American dream.

Land has always been a staple of the American dream. From the Mayflower Compact of 1620, to the Homestead Act of 1862, all the way down to the ongoing battle we face to preserve what we have today … land has always been a integral component and driving force for the American way of life.

Mr. Abercrombie’s family worked their entire lives to earn, maintain and preserve the land they have for the next generation.

He is a steward of this land and the natural wonders around him … just as his great grandfather was.

He stands to lose it all.

The same sentiment played out across the mountain and down in the valley. They treasure the land, and they want to preserve it for future generations.

People like Fran Summerlin, Ben Lyon, Leo Galleo and a host of others led what did indeed become a movement to stop the project. The Alabama Rivers Alliance lauded them with an award for what was called a valiant battle.

The consensus was that the mountain isn’t just a geologic formation, it stands as a monument to history and heritage. It still stands because people cared enough to get involved in a fray most didn’t think they could win. But, they did.

Native American groups stepped in with support for preservation of land their ancestors once lived. Twinkle Cavanaugh and Chip Beeker of the Alabama Public Service Commission visited the mountain, heard the group’s pleas and decided their votes on Alabama Power’s proposal would be ‘no.’

Within days, Alabama Power announced it was cancelling its plans.