Built of tradition, family roots and love

Story by Joe Whitten

Photos by Wallace Bromberg Jr.

Submitted Photos

The white column c. 1910-1911 Watson-Byers House rests on a grassy knoll in Odenville, gleaming in summer sun as lovely as a jeweled tiara resting on a green velvet cushion.

A St. Clair County vintage home, indeed, but for those nurtured by previous Watson parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles, it is a house of unconditional love. Talk with any child, grandchild or cousin, and you hear only happy memories.

The original owner, William Clayton “Will” Watson, was born March 4, 1861, in White Plains, Benton, later Calhoun County, to William Alvin P. and Eliza Ann Hart Watson. Eliza’s father, Andrew Hart, ran Hart’s Ferry on the Coosa River, ferrying between St. Clair and Calhoun counties. The Harts owned and farmed the land where Andrew Jackson constructed Ft. Strother in 1813.

William Alvin P. Watson died at Vicksburg in the Civil War. Widowed Eliza Ann Hart Watson married John Lonnergan in 1869. John and Eliza Lonnergan eventually owned the two-story double dog-trot log home built by John Looney in Beaver Valley. In a recent interview, Will’s grandson, Frank Watson, recounted that family oral history said that “Grandpa Will, when he was 18, rode the horse over to the Looney’s and bought the house for his mother, and then the Lonnergans moved in.” Frank added, “Now, I haven’t checked this out; that’s family lore.”

Will attended Southern Normal School and Business College in Bowling Green, Ky., graduating in 1887. Then, two years after graduating, he married Mentie Cox of Ashville on October 9, 1889. Will and Mentie lived in the Ragland area of St. Clair County, where Will at various times worked as postmaster at Lock Three and as a teacher. Grandson Frank treasures the school bell his grandfather used in his school.

Will and Mentie had a large family of 12 children and desired them to have the best education possible. Therefore, when Odenville was chosen as the location of St. Clair County High School, Will began planning to move his family from Ragland to Odenville.

“It was about 1909 or 1910 that Will bought the land here in Odenville … and they built the house and moved here in 1911,” Frank recalled. Saraharte Watson Byers’ notes indicate it was completed sometime in 1910.

“He cut all the timber over there where he lived and shipped it here by rail, and this house was built out of rough timber,” great-grandson Jimmy Byers added. One of Will and Mentie’s daughters died in 1908, and their last child was born in Odenville. Eleven of their 12 children attended St. Clair County High School. Daughter Roberta graduated in the second graduating class in 1913.

In a conversation with this writer many years ago, Saraharte Watson Byers recounted how that after the house was completed, Will shipped their furniture by rail from Ragland to Odenville. Then the family came by train to their new home and new town. Arriving at the Odenville depot, the Watsons got off the train and walked to their new home. Father led the way, mother behind him, and the children behind her from oldest to youngest and like a moving staircase marched up the road.

For many years, the Watson-Byers House has had the square columns on the front, but those were not on the house originally. Frank reminisced: “It originally had double porches, not columns. I remember when it got changed. Uncle Hop, Will’s son who lived in the house, got tired of that upper porch. It was before they had treated lumber, and he got tired of replacing it; so, they took the upper porch off and put the little portico up there and put up the columns. Originally, a long, wide pathway wound uphill to the porch and visitors always entered at the front door. But the house hasn’t been changed much inside. Maybe the only change in the old house is the kitchen windows. They are double now, and they were single back then.”

Inside the home, a central hall extends front to back with high-ceiling rooms on either side. Most visitors today enter at the kitchen, furnished with table and chairs of the period of the home. The cook-stove looks like a wood-burning stove from 1911 but really is an electric stove that Saraharte Watson Byers had shipped from Canada after she and Alvin became owners. She also installed hardwood floors in all the rooms except the dining room, which retains its original pine flooring, the standard flooring of that day.

The rooms are large as was the turn-of-the-century custom, with tongue-and-groove pine walls rising ten feet. Those tall ceilings made the rooms cooler in the summer, but they could also make for cold rooms in the winter. The house was originally gaslit from a Delco gas system from which gas was piped into the light fixtures. One gas-lamp globe survives in Frank’s possession.

A stairway leads to the second floor where several newlyweds started their married lives —Saraharte and Alvin Byers, Jimmy and Karen Byers, Al and Donna Byers, as well as cousins lived up there.

Frank remembered that the garage and the men’s toilet were across today’s U.S. 174, which did not cut through the property until years after the house was built. The ladies’ toilet, however, was located on the hill behind the house.

Deeply rooted family tree

Frank was only five years old when his grandmother, Mentie, died in 1938 and barely remembers her. However, he recalls well his grandfather, Will. “Granddaddy loved to tell ghost stories to us grandkids, and he would frighten us all to death. He could tell good ones, and he had a knack of telling the punch lines. … He’d tell Civil War ghost stories about when they lived at Lock Three.

“After he came to Odenville, he was a merchant. But he went out of business during the Depression — let too much out on credit. In his later years, he would go down to the local store every day, and he would always carry his long umbrella. The guys teased him about that, and he’d say, ‘Pshaw! Pshaw! It might rain.’ But he was using it for a walking cane!”

Will died in 1950, and his funeral service was held at the house he’d built, just as Mentie’s had been in 1938. Both are buried at Liberty Cemetery, Odenville.

Will’s son, Hobson “Hop” Watson and wife Sally Robison Watson lived in the house with Will, caring for him until his passing. When he died, Hop and Sally became owners of the home and lived there with their daughter, Saraharte, called “Sade” by many friends. She grew up loving the old home, her family, Odenville and the people of the town. Saraharte graduated from St. Clair County High School in 1945. She attended the University of Alabama but earned her undergraduate and graduate degrees from Jacksonville State University. Later she earned her Ed.S. from the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Saraharte Watson married Alvin Byers in 1947. Alvin had dropped out of school in 1944, his senior year, to fight in World War II. When the war ended, he returned to St. Clair County High School and graduated in 1946. Alvin attended JSU and earned a degree in education.

The Byers had three children. Jimmy married Karen Turner, and they have three children Matthew, Adam and Joshua. Al married Donna Colley and they have three children, Rodney, Jeremy and Zeke. Lynn married Jed Brantley and they have two children, Jacob and Rachel. Alvin loved sports and all three children got involved in sports. Lynn could play as well as her brothers. Her comment was, “He taught me to play anything that had a ball in it!”

Both Saraharte and Alvin had careers as teachers in Odenville. Alvin taught various subjects and coached various sports and is well-remembered for his baseball teams and both boys’ and girls’ basketball teams. Both teams went to state playoffs at various times. Saraharte taught elementary grades and retired as head of the elementary school.

Hop and Sally Watson lived in the house until their deaths. Saraharte and Alvin became owners at Sally’s passing. Then Alvin died in 2001 and Saraharte in 2003. After her death, great-grandson Jimmy Byers and wife Karen became owners/caretakers of the lovely old home.

The first thing Jimmy and Karen had to face was the bat infestation in part of the house. And not just any bat, but the protected brown bat, requiring that they be relocated. Only a wildlife relocator could do this. Jimmy located one of American Indian lineage who successfully got them out of the house and relocated. “We probably had a thousand bats,” Jimmy said. “The porch ceiling was sagging from guano. We had to redo the ceiling on the porch and redo two walls in the living room.”

When talking with Jimmy and Karen, their son Matt, and Jimmy’s first cousin, Judy Gibson Banks, one hears memories of loving parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles spilling out as refreshing as a fire hydrant at full flow on an Alabama summer day — memories of a house full of loving kindness.

Jimmy lived his first three years in this house, for Saraharte and Alvin lived upstairs in the house until they could build a home in Moody. Karen commented, “They brought Jimmy home from Leeds Hospital to the Watson House. Saraharte talked about having the heater upstairs and how they had to keep it warm for Jimmy.”

Jimmy’s face broke into a wide smile when this interviewer asked about his memories of his Granddaddy Hop and Grandmother Sally. He chuckled as he began. “Granddaddy was my buddy. I loved him with all I could love anybody. When I was a little fellow, I guess it was in ’54, Granddaddy bought a Shetland pony. We took the back seat out of the car, and we brought the pony home in the car. We named him Buckshot and he actually lived to be 34 years old.

“Later we had horses, but we had Buckshot before we had anything else. And because me and my brother Al were just kids and weren’t good with the reins yet, so Granddaddy would lead us all over the pasture — us on Buckshot.”

When Jimmy paused to reflect, Karen added, “Jimmy talked about Granddaddy riding him and Al around the pasture; well, he did the same thing with our boys. He would sit them on the pony and ride them around the pasture and they loved it. Our boys loved their Grandmother and Granddaddy Watson.”

“This happened later,” Jimmy continued, “but Granddaddy was — how can I put this — was feeling pretty good one day, and he brought Buckshot up the steps and into the living room and Buckshot messed in the floor. Needless to say, Grandmother put him and Buckshot back out of the house!”

Judy Gibson Banks and her sister Wanda grew up in the Byers’ home under the guardianship of their Uncle Alvin and Saraharte. Hop and Sally happily added them as grandchildren. Judy lovingly remembered “Grandmother and Granddaddy” and the good times she had at their house on the hill. “The horses were up there at the Watson House. Wanda and I started working with the horses, and we rode horses all over that hill. But Granddaddy would worry about us, so when we were riding — no matter where we were on that place — we could look up and Granddaddy would be somewhere on that hill watching to make sure we were OK.”

Hop and Sally loved their grandchildren and the grandchildren’s love for them comes shimmering through in interviews. Karen commented, “Hop and Sally, were two of the most giving people you would ever meet. She welcomed everybody into this house. The football team — Jimmy and Al would bring folks home, and some of ‘em stayed. She was so good about that. Always had food for them, cooked for them.”

On the way to school each morning, Sade would drive her family to school, stopping at Sally’s to check on her. Every afternoon they would stop by again. A fond memory that lingers is how almost every afternoon Grandmother Sally would have divinity, or pound cake, or some snack for the grandkids after a long school day.

When Jimmy started college in Jacksonville, he recalls that when he and David Veasey commuted together, “I’d pick up David in Moody and then we’d come by here every Sunday evening when we headed to Jacksonville. And she’d fix us snacks for the week and feed us before we started up there.”

Legendary fried chicken and more

Sally’s cooking was legendary in the family. Jimmy remembered, “Every weekend we ate up here at Grandma’s house. And on Sunday — she had the best fried chicken you ever would eat. In all my life, I’ve never tasted any as good as hers.” He said that eating at Grandma’s on Christmas was like eating at a cafeteria she had so many dishes. “She was a diabetic,” Jimmy noted, “but she cooked it all!”

Jimmy’s sister, Lynn, joined the dinner-memory choir, saying, “Sunday dinner at Grandmother’s was amazing. She made the best fried chicken around.”

Lynn also spoke of her love for Granddaddy Hop. “I loved just spending quality time with my Granddaddy. He was one amazing man. I loved listening to all the stories Granddaddy would tell us.”

Another occasion for family meals occurred Easter Sunday. The family would attend church and then to Grandmother and Granddaddy’s house for a big meal — and of course it included Sally’s fried chicken! After lunch, the kids hunted Easter eggs hidden over the hilltop.

The family enjoyed telling about Hop’s pipe and Sally’s cigarettes. “Granddaddy smoked Prince Albert tobacco in his pipe,” Jimmy related, “and Grandmother smoked cigarettes. Well, she got tired of buying rolled cigarettes, so she used a brown paper bag. She would cut the paper bag up and roll her cigarettes using Granddaddy’s Prince Albert tobacco and smoke those brown sack cigarettes.” Sally bought cigarettes only when they visited relatives.

Sally did all the driving, for Hop never drove a car. The grandchildren told how when school was out in the spring, Sally would load the family in her car to visit relatives in various towns in north-central Alabama. “Granddaddy always went with us, but he had little patience with visits and was ready to leave soon after arriving,” Jimmy remembered.

Although Hop never drove an automobile, in his later years, he bought a riding lawnmower and had a good time riding it all over the home-place hill. Today, where he had such a good time, his descendants had enjoyed festive occasions. In the past several years, the hilltop has been used for wedding events.

Quiet home weddings have occurred in the home, including Donna Colley and Al Byers and Judy Gibson and Curtis Banks. However, Jimmy and Karen, wanting family members to continue enjoying the old home place, have hosted the garden weddings and receptions for family members. The first one of these was for Lynn and Jed’s daughter, Rachael. The ceremony took place on the wide front porch with guests sitting in chairs set up on the lawn. A white tent in the back, where Hop drove his lawnmower, served for the reception and dancing with a live band.

One can hope that Hop and Sally and Sade and Alvin (should he be interested), somehow get a glimpse of those festive events at their well-loved old home.

Great grandchildren also have delightful memories of Hop and Sally Watson. Matt Byers in a college essay wrote this:

“The greatest man I ever knew was Hop Watson, my great-grandfather. … No child could have known a more caring, loving and understanding human being. … I remember the look in his eye when his ‘little man’ would do something he’d taught him and do it right! From riding mop ponies to real ponies, I learned it all from him. He taught me so many things about life, the land, and most importantly, about love. … When my brother, Adam, came along, I had to share my granddaddy. That was tough for me, but I managed. … With the help of our granddaddy, we thought we could do anything. He loved us dearly and we loved him. After Granddaddy passed on, I made a promise to myself to let everyone I cared about know it. … I still think about him today. His influence over my life is still prominent and I owe him a lot. I just wish that I’d told him how much I loved him. So, to ‘the greatest man I ever knew,’ I love you.”

In a recent conversation, Matt joined the “Hallelujah Chorus” of Sunday dinner at “Nana’s and Granddaddy’s house. My great-grandmother fried chicken like nobody else. Her recipe, which to my knowledge has not been matched in St. Clair County, drew people from miles around. Everyone wanted some of that delicious, crispy-hot poultry. Granddaddy Watson had fresh corn and other vegetables to go with it. And if it was July, you could thump the watermelons and enjoy something delightful. Those were the days!”

A Christmas tradition

Shawn Banks, Judy and Curtis’ son, remembered Christmas time. “Some of my happiest memories are of Christmas at Granddaddy and Nana Watson’s home. Each year, a week or two before Christmas, Granddaddy would gather the grandchildren and set out to find the ideal tree. After traipsing down the hill, across the highway, through the woods along the creek, we would find our tree.

“When the tree was in place, everyone would gather in the living room to decorate our prize. We hung the stockings and … when the decorating was finished, Nana would say, ‘Isn’t that pretty?’ My favorite time was topping the tree with the star. Not an elaborate star; just a simple one that Granddaddy had made of cardboard and covered with tinfoil. Each year, a different grandchild got to put the star on the tree. It was an exciting time when my turn came around.”

To Shawn, the memory of that homemade Christmas star is “…a spark of inspiration. A little spark that could relight the ashes of burnout, until we spring forth like the Phoenix, finding a new zest and appreciation for family and happy memories.” Today, the cherished star radiates memories throughout the year from its protected place in a curio cabinet.

Sally and Hop were icons in Odenville, as were Sade and Alvin. Their many years of teaching in the elementary and high school bring fond memories to Odenvillians, many now in the senior citizen years.

Ode to Sade

Sade’s students undoubtedly remember her love for Alabama and Odenville history. She diligently collected local history and shared it with her students. When an Odenville history project was under way, she tracked down vintage photographs and located individuals who could contribute to the needed information. She was a cheerleader for Odenville.

Family members agree that Sade was the “Rock of Gibraltar” of the family and her heart was full of love for family and friend. Karen recalled Sade’s love for people and how she wanted everybody welcomed who came to the house, making sure that each had been introduced around to the others. Having grown up in a loving home, Sade knew how to love generously. That is a beautiful legacy expressed by her poet grandson, Matt Byers.

“Sade”

The picture of what love should be

Was seen upon her face.

The matron of our family

Displayed her love with grace:

Examples of how we should live

In order to bear fruit —

Examples of the way

To give to others as our root —

For Sade was more than we could see,

A wife, a mom, a saint.

A Mimi’s grandiosity

Whose ways were calm and quaint.

She cared for all as if her own

And never so for gain.

Her seeds of love were aptly sown,

Forever to remain.

Some sunny day, should you drive by this lovely home, think on this: Happy memories are built on love, and love endures long after a dear one has left us behind. Such is the history of the Watson and Byers families.

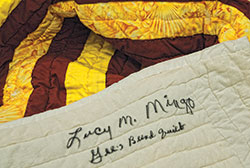

Quilts and quilters have compelling stories to tell

Quilts and quilters have compelling stories to tell Quilts came to the New World with the first settlers and were necessary in the home well into the 20th century.

Quilts came to the New World with the first settlers and were necessary in the home well into the 20th century. Now look at a Gee’s Bend quilt and realize the placement of color, fabric texture and shape speak a language of mood or emotion, unhampered by strict adherence to geometrical pattern and form. The green-bordered Double Glory quilt by Tinnie Pettway (Claudia’s mother) is as lively as New Orleans jazz vibrating the night.

Now look at a Gee’s Bend quilt and realize the placement of color, fabric texture and shape speak a language of mood or emotion, unhampered by strict adherence to geometrical pattern and form. The green-bordered Double Glory quilt by Tinnie Pettway (Claudia’s mother) is as lively as New Orleans jazz vibrating the night.

When Blythe and family left North Carolina and headed west, he instructed his wife to tell no one that he had preached. No written record states exactly why he had become so disheartened; however, his friend and Alabama Baptist historian, Hossa Holcombe, hinted that the problem was a theological difference with North Carolina pastors concerning man’s free will.

When Blythe and family left North Carolina and headed west, he instructed his wife to tell no one that he had preached. No written record states exactly why he had become so disheartened; however, his friend and Alabama Baptist historian, Hossa Holcombe, hinted that the problem was a theological difference with North Carolina pastors concerning man’s free will. But being declared free and grasping the reality of freedom are two concepts not comprehended quickly. Former slaves, now free to congregate and worship together, continued to meet with Mt. Zion until 1868.

But being declared free and grasping the reality of freedom are two concepts not comprehended quickly. Former slaves, now free to congregate and worship together, continued to meet with Mt. Zion until 1868. Mrs. Long reminisced about the singing in the church. “They had people in the choir, and they sang the old-fashioned songs. Mattie Kelly was the pianist. She would play the piano, and they would sing. When she finished, she would always shout. She was one of the shouting sisters in church.” Another pianist was Mattie Jo Williams Herring.

Mrs. Long reminisced about the singing in the church. “They had people in the choir, and they sang the old-fashioned songs. Mattie Kelly was the pianist. She would play the piano, and they would sing. When she finished, she would always shout. She was one of the shouting sisters in church.” Another pianist was Mattie Jo Williams Herring.

A pinnacle of St. Clair History

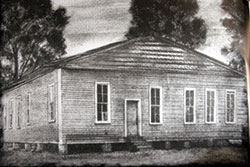

A pinnacle of St. Clair History The date that Mt. Lebanon Church started worshiping together is not known, but they likely met in the Mt. Lebanon school building. It is known that the Mt. Lebanon First Congregational Methodist Church officially organized in July 1905 and that William Robinson, a Congregational minister, would come from Georgia to the mountain to visit his Robinson relatives. While on these visits, he conducted revival meetings, and one of these revival meetings culminated in the establishing of Mt. Lebanon Church. William Robinson served as the first pastor from 1905 to 1911.

The date that Mt. Lebanon Church started worshiping together is not known, but they likely met in the Mt. Lebanon school building. It is known that the Mt. Lebanon First Congregational Methodist Church officially organized in July 1905 and that William Robinson, a Congregational minister, would come from Georgia to the mountain to visit his Robinson relatives. While on these visits, he conducted revival meetings, and one of these revival meetings culminated in the establishing of Mt. Lebanon Church. William Robinson served as the first pastor from 1905 to 1911.

The Vandegrifts became leaders in community and church. In 1835, Christopher served as an elder in the organization of Liberty Cumberland Presbyterian Church. In today’s Odenville Presbyterian Church, Christopher’s descendants worship and serve there, continuing the godly influence of their ancestors.

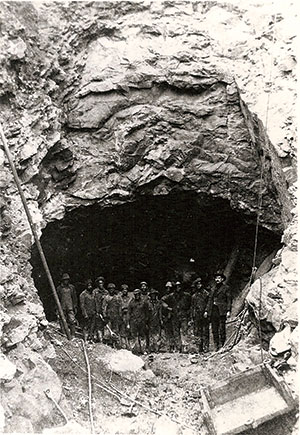

The Vandegrifts became leaders in community and church. In 1835, Christopher served as an elder in the organization of Liberty Cumberland Presbyterian Church. In today’s Odenville Presbyterian Church, Christopher’s descendants worship and serve there, continuing the godly influence of their ancestors. Pickens served in Company C, 18th Infantry Regiment, Confederate States of America. Roland Holcomb recounts a Pickens’ story that happened when the railroad was being put through Odenville very early in the 20th Century. He had given the Seaboard Airline the land and rights to build a tunnel through the mountain as long as the tunnel be called Hardwick and that the train would stop there. Seaboard Airline agreed.

Pickens served in Company C, 18th Infantry Regiment, Confederate States of America. Roland Holcomb recounts a Pickens’ story that happened when the railroad was being put through Odenville very early in the 20th Century. He had given the Seaboard Airline the land and rights to build a tunnel through the mountain as long as the tunnel be called Hardwick and that the train would stop there. Seaboard Airline agreed.

Eden school has storied history

Eden school has storied history Early 20th Century schools no longer here

Early 20th Century schools no longer here Friendship School, of field-stone construction, still stands today and is owned and used by Friendship Baptist Church. Though the date of origin is obscure, in the 1920s, C.J. Donahoo was principal, and Mrs. Bertha Bowlin was a teacher.

Friendship School, of field-stone construction, still stands today and is owned and used by Friendship Baptist Church. Though the date of origin is obscure, in the 1920s, C.J. Donahoo was principal, and Mrs. Bertha Bowlin was a teacher.