A pinnacle of St. Clair History

A pinnacle of St. Clair History

Story by Joe Whitten

Submitted photos

Rising to an elevation of approximately 1,315 feet in the northern part of St. Clair County, Chandler Mountain extends from the southwest to the northeast for about 10 miles.

Its average width is about two and a half miles with an area of about 25 square miles. The terrain is rugged with numerous outcroppings of rock.

According to Place Names in Alabama (The University of Alabama Press, 1999), by Virginia Foscue, the mountain got its name from Joel Chandler, “who brought his family to this area soon after the Creek Indians were removed in 1814.” He settled on Little Canoe Creek. The mountain behind his place provided good hunting, and hunters, who used a trail near his property to climb to the hunting ground, began calling the mountain Chandler’s Mountain. In time, the apostrophe “s” was dropped, and Chandler Mountain has been the name since.

Despite the rugged terrain, settlers arrived. The first, Cicero Johnson from northwest Georgia, entered land on Chandler Mountain in 1855. Historian Vivian Buffington Qualls records that others soon came with their families from Georgia and the Carolinas to join Johnson: Franklin Smith, Jake Lutes, John Bearden, W.V. McCay, John Hollingsworth, Boze Wood, Jake and Bob Robinson, John Hollingsworth and Levi Hutchens. Hezekiah McWaters came from Troy, Alabama. So, the area began to be settled and cultivated.

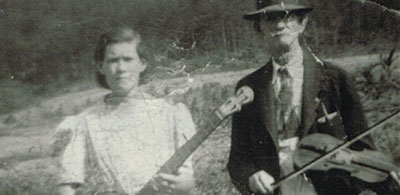

Darrell Hyatt tells a family story of his Robinson great grandfather, George, who as a boy learned to play the fiddle. During the Civil War, when Confederate troops had camped between today’s US 231 and the Beason House, George would entertain them by playing the fiddle. Years later, George married Susie, who played the banjo. Darrell shared a treasured photo of the couple—Susie holding her banjo; George, his fiddle.

An interesting feature of this Chandler Mountain lies in the water level. Water for family and livestock came from dug wells or creeks on the mountain and in the valley. According to written sources, mountain well-diggers struck water within 25 or 30 feet, whereas in the valley, wells sometimes went as much as 75 feet down before finding water.

Lee Gilliland and Larry DeWeese, who grew up on the mountain, said that early on, wells were hand-dug and lined with rock, brick or wood. They also spoke of “punched wells.” A bit about 4 inches in diameter and attached to a long heavy tube was mounted on a truck. A motor pulled the tube high and then let it drop, pounding it into the earth. This process took up to two weeks before it reached the water source. The steady pounding could be heard for quite a distance.

Numerous springs bubble from the ground, but the water doesn’t flow far before sinking back into the earth. In 1949, D.O. Langston wrote his master’s degree thesis at Auburn University about Chandler Mountain. He stated that “Gulf Creek is the only stream that flows any distance, and its water disappears in dry seasons.”

Two roads give access to the mountain: Steele Gap on the east and Hyatt Gap on the west. Hyatt Gap is named for John M. Hyatt, who migrated from Heard County, Georgia, around 1875.

For his master’s thesis, Langston interviewed Hillard Hyatt, who gave an account of John Hyatt’s coming to Chandler. Hillard told that John, living in Georgia, fell in love with a young woman. Her parents objected to the courtship, so John came to his cousin, Hezakiah McWaters, on the mountain. After working for McWaters “for a year or so,” John bought “80 acres near the southwest end of the mountain.” Then, “…he went back home to Heard County, married his childhood sweetheart, and they came back home, bringing all they possessed on one small pony. They arrived with 20 cents in money.” John’s 80 acres included what is today’s Horse Pens 40, an international tourist and recreational attraction because of its centuries-old rock formations. Its history includes an ancient Native American burial ground, a hideaway during the Civil War and for outlaw Rube Burrow. It was nationally known for bluegrass festivals with rising stars of the day like Lester Flatt, Bill Monroe, Charlie Daniels, Ricky Skaggs and Emmylou Harris. Today, it is home to world class bouldering, hosting the triple crown climbing championship.

Darrell Hyatt recounted that family lore named John Hyatt as the last person to be granted a homestead in Alabama and that John and wife arrived here with all they owned in a pillow case. Wikipedia says the park derived its name from the original deed when allocating the acreage: “the home 40, the farming 40, and the horse pens 40.”

Organization of schools and churches

According to Mrs. Qualls, the first school on Chandler was called Mt. Lebanon. The building was across the road from today’s Mt. Lebanon First Congregational Methodist Church. A note written in old minutes of the church states, “A building was near the site of Mt. Lebanon Church in the late 1880s and was used for school meetings.”

The Mt. Lebanon School was on the east end of Chandler. On the west end, around 1895, the McCay School was organized. Mrs. Qualls records that John Hyatt had recently built a new house and donated the logs from his old home for the school building on the McCay property. Langston states, “After this house was built, the school then alternated between the church located on the east end of the mountain and the school on the west end. The church being on the east end and the school on the west made it necessary to alternate between the two to keep peace and harmony. …” Then, in 1902, the school relocated to a new building on the Hollingsworth property.

The two schools eventually consolidated, and in time the school became the Chandler Mountain Junior High School, which flourished for many years. The students consistently made high scores on the yearly standardized tests. The county school system closed the school and today buses students to Steele and Ashville.

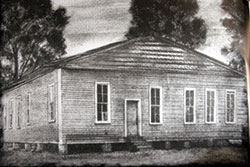

The date that Mt. Lebanon Church started worshiping together is not known, but they likely met in the Mt. Lebanon school building. It is known that the Mt. Lebanon First Congregational Methodist Church officially organized in July 1905 and that William Robinson, a Congregational minister, would come from Georgia to the mountain to visit his Robinson relatives. While on these visits, he conducted revival meetings, and one of these revival meetings culminated in the establishing of Mt. Lebanon Church. William Robinson served as the first pastor from 1905 to 1911.

The date that Mt. Lebanon Church started worshiping together is not known, but they likely met in the Mt. Lebanon school building. It is known that the Mt. Lebanon First Congregational Methodist Church officially organized in July 1905 and that William Robinson, a Congregational minister, would come from Georgia to the mountain to visit his Robinson relatives. While on these visits, he conducted revival meetings, and one of these revival meetings culminated in the establishing of Mt. Lebanon Church. William Robinson served as the first pastor from 1905 to 1911.

The church purchased land on which to construct a building from Bent Engle. They paid $2 an acre for two acres. A penciled note in some old minutes record that Jeff Smith donated land for the cemetery.

From 1933 to 1936 the church had a woman pastor—Annie Struckmeyer Moats, an ordained minister in the Congregational Church. Annie’s husband was Alley Mathis Moats. Annie’s granddaughter, Barbara Robinson, is a current member of the church.

Mt. Lebanon celebrated its centennial in 2005, and as it has done for over a century, remains a vibrant contribution to Chandler Mountain.

Chandler Mountain Baptist Church through the Years—1910-2010, compiled by Ellis Lee Gilliland and Mary Gilliland, recounts that on Oct. 22, 1910, members of the Missionary Baptist Church met at Cross Roads, or as some called it, Pleasant Valley, in Greasy Cove District near Gallant, Alabama, and organized a missionary Baptist church. The organizing presbytery consisted of John Heptenstall, Colman Buckner, Mon Umphres, J.D. Vicars, J.B. Rodgers and H.H. Turley.

Minutes dated Nov. 6, 1910, give that name as Cross Roads Baptist Church, which indicates that was its first name. These minutes show the church elected John Heptenstall as minister and M.C. Rogers, son of Deacon J.B. Rogers, as church clerk.

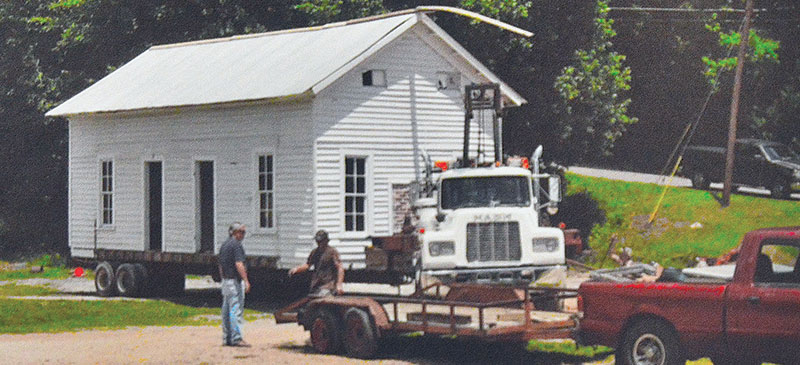

Years passed, new buildings replaced outgrown ones, and in March 2001, the church named a committee to proceed with plans for building a new sanctuary with a basement fellowship hall and to obtain a loan for a stated amount. The committee completed its job, and worship services moved from the old 1948 building into the new. The first service in the new building occurred on Sept. 9, 2001. The church paid off the loan in 2011. They used the 1948 building as a youth facility.

Then in 2017, structural weakness in the trusses caused unsafe conditions in the new sanctuary, and the congregation had to meet in the old building again. Over the years, church members have been faithful and resilient in difficult times, and so has it been in this set-back. The repairs haven’t been completed yet, but the church is making progress and looking forward to being back into the 2001 sanctuary.

Chandler Mountain Baptist Church celebrated its centennial in 2010 and continues its 108-year legacy of a faithful church body that is a source of spiritual strength to the community.

Lumber and Sawmills

The Ashville Museum and Archives has photocopies of articles Kenneth Gilliland wrote of his family and the mountain. One tells of the logging industry of the 1920s. There were sections of timber that had never been cut over and contained “a large supply of virgin timber, mainly pine trees. The pines were tall and straight. We called them ‘Old Field’ pines. Many of the trees would yield 12” x 12” timbers, eighteen to twenty-four feet long.”

Kenneth’s and Lee’s daddy, Sylvester Gilliland, built a portable sawmill that he could move into a tract of timber and have it set up in a day or two. Kenneth wrote, “A gasoline automobile engine was used to power the mill. Daddy used an engine out of a 1927 Buick for many years. He equipped it with a gravity-fed carburetor system from a Model A Ford. He would saw 8 to 12 thousand board feet of lumber a day if all went well. … The trees were all cut down and cut into logs of the correct length by two-man crosscut saw” and the “… logs were snaked in by mules.”

In those days, men found work wherever they could — usually for $1 a day. Gilliland paid his workers $2.50 a day because “they were worth it.”

In an interview, Lee Gilliland commented that his dad could do anything he set his mind to. His brother, Kenneth, recorded one such endeavor — electrifying their home seven years before Alabama Power climbed the mountain with their electricity in 1939-40. He wrote: “…electricity came to the S.B. ‘Vester’ and Dora Gilliland family about 1932. Daddy installed two 32-volt D.C. Delco Light Plants. They were set on concrete slabs in the corner of the garage. These were a one-cylinder gasoline engine pulling a direct coupled D.C. generator. These engines would run on kerosene also. They would charge a bank of lead/acid batteries. Wire was run from the bank of batteries into the house. Mom’s first appliance was a 32 V.D.C. iron bought from Teague’s Hardware in Ashville.”

In a 1977 interview with Dale Short of The Birmingham News, Sylvester Gilliland said, “The first 5 dollars I ever got hold of after I was grown, I sat down with the Sears-Roebuck catalog and ordered me a book about automotive mechanics. Most folks around thought I was a little touched, because not only did we not have any sign of a car, but even if we had, we couldn’t have got it on or off the mountain, roads being like they were.”

Observing that Gilliland devoured the automotive book, then ordered a book about steam power, then one about hydraulics, and then one about radios, Short commented, “Now he can look back over half a century of keeping sawmills whirring, gins ginning, mowers cutting, and in later years, radios and televisions playing.”

It would be correct to say that Sylvester Gilliland was the right man at the right time for Chandler Mountain.

Peach paradise?

Many do not know that mountain farmers grew peaches and sold them commercially. A Mr. Sloat and a Mr. Bush came from Michigan and introduced peach orchards to Chandler Mountain. Just when they came and what their first names were seem unrecorded, but it can be surmised they arrived toward the end of the 19th century. Sloat and Bush convinced the farmers, and they planted several thousand trees.

Vivian Qualls writes that around 1907 W.L. Yeilding from Birmingham bought Sloat’s orchard. She quotes Yeilding’s son, Ency, “The farm included about 200 acres of land, one-half of which was in peach trees. … The original trees … were about 7,500. About three years later, he began to plant another orchard of between 3,000 and 3,500 trees.”

Mr. Langston wrote that the men built a stone packing shed near the railroad depot in Steele, and “the trees bore their first crop about 1900. The fruit was of a desirable kind and of very high quality. The packing house was ready. The crop, properly graded and packed, sold for a good price. The farmers were well pleased with their new adventure.”

Several years of good peaches selling for good prices followed. Then the bottom fell out of the market. Langston records that one farmer hauled 304 bushes of high quality peaches to Steele and returned home with $12.08. His crop brought about four cents a bushel.

Mrs. Qualls relates that the Yeildings built a canning plant so the peaches could be preserved and sold when prices went up again. For a few years the peaches were canned. However, Langston notes that when the average life of the first trees ran out, none of the farmers were willing to replant, and the peach industry dwindled out.

Tomatoes become king of mountain

Both Qualls and Langston record that Otis Hyatt, son of John Hyatt, raised the first crop of tomatoes marketed from Chandler Mountain. Over the years, Otis had learned farming from his father, John Hyatt.

John became a successful grower of garden produce. At some point, he raised enough to make it profitable to take the produce down the mountain to sell. Needing a more convenient road than Steele Gap, Mr. Hyatt built the road known today as Hyatt Gap.

Mr. Langston records that John built the road “single handed down the mountain to Greasy Cove.” Darrell Hyatt recently added that his great grandfather used a “team of oxen and a slip scrape” to build Hyatt Gap Road. The gap was paved in the 1970s.

In a 1940s interview with Mr. Langston, Otis gave 1926 as the first tomato year. He raised the crop, harvested it, packed the tomatoes in baskets and peddled them. He received “on the average one dollar per basket.”

The next year, his brothers planted tomatoes and sold them the same way. The brothers established routes and delivered tomatoes three times a week. Through experimenting with planting times, they found they could harvest from July to October, for first-frost came later on the mountain than in the valley.

Langston records that the Hyatts’ “… neighbors soon began to follow the same practice, and by 1932, the local markets could not take care of the crop produced.” Thus, began the crop that has made Chandler Mountain famous.

Production increased, and by 1940, McDonald Produce Company of Terry, Miss., was sending trucks to the mountain to be loaded with tomatoes for selling in Mississippi. With a longer growing season on the mountain, Mississippi and other states realized they could have fresh tomatoes into late autumn for their markets. In 1948, The Southern Aegis reported that the farmers shipped tomatoes to buyers “from New York to Miami.”

The farmers banded together and formed the Chandler Mountain Tomato Growers Association in 1943. As recorded by Langston, the following men were the first directors: Farmer Rogers, Cecil Smith, Hershal Smith, J.D. Osborne and Clarence Smith. The association incorporated in 1945. There were two packing houses for processing the crops, and that year, the association graded approximately 30,000 bushels of tomatoes.

Production continued to increase, and in 1946, Ross Roberson and J.D. Osborne built packing sheds near Whitney on the Birmingham to Chattanooga highway—U.S. 11. In 1947, the association processed 60,000 bushels of tomatoes, some coming now from Blount County farms.

As the 1948 season progressed, farmers saw excellent harvests and sales. October came with prices reaching $3.50 a bushel. Then disaster struck. As reported in the Oct. 22, 1948, issue of The Southern Aegis, an “unseasonable ‘snap-freeze’ that swept over most of Alabama Sunday night (October 17)” ruined an estimated 40,000 bushels of tomatoes. The Aegis put the financial loss at between $100,000 and $150,000.

Most farmers are invincible, and gradually tomato farmers recovered, and production still flourishes today.

So, the next time you slather mayonnaise on two pieces of white bread and cut thick slices of Chandler Mountain goodness for your sandwich, remember Otis Hyatt, who started it all.

And as you take your first juicy bite, whisper thanksgiving to the Lord for this summer satisfaction!

The Vandegrifts became leaders in community and church. In 1835, Christopher served as an elder in the organization of Liberty Cumberland Presbyterian Church. In today’s Odenville Presbyterian Church, Christopher’s descendants worship and serve there, continuing the godly influence of their ancestors.

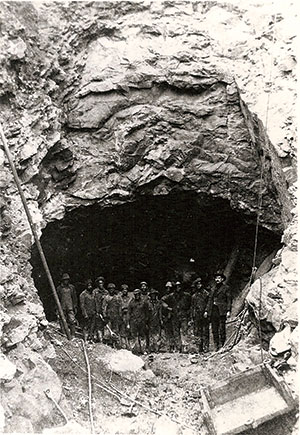

The Vandegrifts became leaders in community and church. In 1835, Christopher served as an elder in the organization of Liberty Cumberland Presbyterian Church. In today’s Odenville Presbyterian Church, Christopher’s descendants worship and serve there, continuing the godly influence of their ancestors. Pickens served in Company C, 18th Infantry Regiment, Confederate States of America. Roland Holcomb recounts a Pickens’ story that happened when the railroad was being put through Odenville very early in the 20th Century. He had given the Seaboard Airline the land and rights to build a tunnel through the mountain as long as the tunnel be called Hardwick and that the train would stop there. Seaboard Airline agreed.

Pickens served in Company C, 18th Infantry Regiment, Confederate States of America. Roland Holcomb recounts a Pickens’ story that happened when the railroad was being put through Odenville very early in the 20th Century. He had given the Seaboard Airline the land and rights to build a tunnel through the mountain as long as the tunnel be called Hardwick and that the train would stop there. Seaboard Airline agreed.

Eden school has storied history

Eden school has storied history Early 20th Century schools no longer here

Early 20th Century schools no longer here Friendship School, of field-stone construction, still stands today and is owned and used by Friendship Baptist Church. Though the date of origin is obscure, in the 1920s, C.J. Donahoo was principal, and Mrs. Bertha Bowlin was a teacher.

Friendship School, of field-stone construction, still stands today and is owned and used by Friendship Baptist Church. Though the date of origin is obscure, in the 1920s, C.J. Donahoo was principal, and Mrs. Bertha Bowlin was a teacher.

A needlework plaque on the kitchen wall says it all: Hard work is the yeast that raises the dough. John, his wife Sara, and Gayle Hammonds were prime movers for the entire project and continue their leadership roles today, but other folks and factions have generously lent their support.

A needlework plaque on the kitchen wall says it all: Hard work is the yeast that raises the dough. John, his wife Sara, and Gayle Hammonds were prime movers for the entire project and continue their leadership roles today, but other folks and factions have generously lent their support. In addition, its main purpose is to serve as a rentable venue for small community group functions, including club meetings, showers, parties and other gatherings. Although actual occupancy is limited by fire law to 16, Gayle says there is ample level lawn space for tents, booths, outdoor festivities and overflow crowds.

In addition, its main purpose is to serve as a rentable venue for small community group functions, including club meetings, showers, parties and other gatherings. Although actual occupancy is limited by fire law to 16, Gayle says there is ample level lawn space for tents, booths, outdoor festivities and overflow crowds.

In April, Progress reported that folks in Ashville and Springville claimed “inside information,” and were of the opinion Pell City had “no chance” of being selected. But rather than losing heart, Pell City published that they had “the best chance” based upon the facts submitted in connection with the state’s proposal for location.

In April, Progress reported that folks in Ashville and Springville claimed “inside information,” and were of the opinion Pell City had “no chance” of being selected. But rather than losing heart, Pell City published that they had “the best chance” based upon the facts submitted in connection with the state’s proposal for location.

On the other hand, floors are littered with a veritable snowfall of white flakes of ceiling paint and decades’ worth of other detritus. In some secluded spots, there is bat guano. Leftovers from several former users are piled here and there. Reconstruction materials are stacked haphazardly among the chaos.

On the other hand, floors are littered with a veritable snowfall of white flakes of ceiling paint and decades’ worth of other detritus. In some secluded spots, there is bat guano. Leftovers from several former users are piled here and there. Reconstruction materials are stacked haphazardly among the chaos.