Story by Carol Pappas

Photos by Mackenzie Free

Curiosity got the best of Granger Waid, and Big Canoe Creek Nature Preserve is lucky it did. Same holds true for Joey Breighner. And again, the preserve was on the receiving end of this lucky charm.

Their names often pop up when Preserve Manager Doug Morrison recounts the contributions the pair made to transform the preserve into nature’s gift to all who visit.

“Early on, the preserve seemed to be some type of clandestine operation hidden behind poorly secured cattle gates,” Waid said, recalling his morning commute past the 422-acre site. “It always begged the question, ‘What is going on with this place?’

“One day my curiosity overtook me. I parked at the gate and started walking. Following the little iron ore-stained trickle upstream, I came across an old spring house with remnants of the old home place on the hill above. I thought to myself, “What is going on with this place?”

That was four years ago. Fast forward three years, and Waid was at a pre-bid conference for his company, Norris Paving. The conference was for a new parking lot being installed at Turkey Creek Nature Preserve. He finally asked his “nagging question” about Big Canoe Creek of Charles Yeager, Turkey Creek’s manager, and his response was, “You need to meet my buddy, Doug.”

Morrison and Waid met, he toured the property and saw the potential. “Doug shared his vision for the preserve, and I saw that it could be something truly special. I knew right then I wanted to be a part of it.”

It is much the same story for Breighner. He came. He saw. He got involved.

“I was familiar with the preserve, but when Doug invited me to the preserve and seeing his passion for the project, I immediately became interested and seeing where I may be able to contribute,” said Breighner, an engineer by trade. “After a tour of the preserve, I saw quickly where there were land surveying and engineering needs where we could jump in and help.”

Lucky for the preserve, both men’s expertise matched their enthusiasm, and they went to work. “I had no idea that it would turn into a full-blown passion project,” said Waid, who also holds degrees in landscape and horticulture. “My wife would call it an obsession, but she gets me, and is one of the few who sees that it’s more to me than building a parking lot and putting plants in the ground,” he said.

“Nature is a necessity for me,” he continued. “There is a healing power in the sound of running water, and sometimes a sturdy oak’s trunk is the best shoulder to cry on. So, I’m all for the preservation of wild lands, because a quiet walk in the woods may be the only under-prescribed medication in America.”

Breighner, too, talks of the healing effect of this particular project. “It’s always gratifying to look back – and forward in this case – on a project where you may have had an impact or feel you have made some contribution.

“The vision had already been cast; we came in and helped where we could, working directly with Doug, the City of Springville, and the site contractor,” Breighner recalled. “As professionals, we are often cautious about projects we support and involve ourselves with. However, after an in-depth introduction to the preserve and an understanding of the short-and long-term vision, it became quickly obvious that this was a project that I wanted to be part of and contribute to.”

The skills Schoel possesses as a company in the field of engineering and land surveying was “a great fit,” Breighner said. “There will be a life-long connection to both the preserve and the people we have been able to work with.”

Waid’s personal philosophy melded with his professional ability, he said, sharing a story of his own. “At our wedding, we gave away tiny ‘Snowflake’ Hydrangeas and said, ‘Let love Grow.’ You can’t take a building seed and plant it to share,” he said.

“Buildings don’t grow with age, they don’t change colors in the fall, or bloom in the spring. You can’t eat them – well, maybe gingerbread houses – and they certainly don’t get to be 100 feet tall all by themselves. Landscapes evolve. They are four dimensional. Having the ability to see a space that doesn’t exist, from every angle, at all times of the year, imagining its future, and combining it with paving, concrete, stone, and steel is a unique skill set that I guess I have.”

He had to have a little help, of course. He likens it to a recipe, adding “a fleet of GPS machine-controlled heavy equipment, a little AutoCAD, sprinkle on some engineering, and for something a lot bigger than shovel and wheelbarrow can produce. Just add diesel fuel and long hours.”

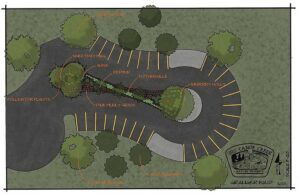

Waid noted that some of the earthwork had been done by the county, but it was clear there was not nearly enough parking. “We donated the men and equipment for a couple weeks and built the lower parking lot and expanded the upper parking lot.”

With Breighner’s help in engineering, “that led to the design and installation of the upper parking, roads and bioswale.”

What will be the preserve’s greatest impact going forward? “Some will say the economic impact in the community, an amenity for the city, others, the opportunity to enjoy the outdoors, hiking, biking, horseback riding, etc.,” Breighner said.

“I see the primary impact as having a nature preserve in St. Clair County, that will be held undeveloped, in perpetuity, with unimaginable diversity available for public enjoyment. The Big Canoe Creek in itself, stands alone in the country with its biodiversity.”

He wants others to have an opportunity to share his appreciation of what can be discovered and enjoyed there. “I have met some incredible folks and made some lifelong friends,” Waid said. “I’ve learned to appreciate the little critters that often get overlooked because they’re not on your hunting and fishing license. Like mussels and darters or sculpins, and salamanders.”

And there’s more, he said. “Surrounding wooded areas filled with flora and fauna unique only to our region will be available to families and children forever. The diversity of the preserve will provide education opportunities for our children, research opportunities for academia that are available only in this region.”

Breighner talked of the trails with varied elevations providing different challenges for hikers, bikers and horseback riders.

“With the preserve in its infancy, and much work left to be done, I don’t know if I can fully imagine the current and future impact the Big Canoe Creek Nature Preserve will have on this community and the surrounding areas.” He looks forward to the future as it continues to grow, add amenities for visitors and, lucky for the preserve itself, “where I can work with the Nature preserve team.”

Waid captures his glimpse of the future like this: “My hope is to keep people curious. Wandering and wondering is important. Maybe they’ll take a moment to stop, lean against a tree and just soak it all in.

“I also hope that the Preserve will impact some kids and will recruit some apostles to go and spread the clean water gospel. We could use some more Loraxes in the future. The world has enough Oncelers,” he said, referring to Dr. Suess’ fictional characters in chronicling the plight of the environment.

“More than anything else, I hope people take a memory with them,” Waid said. “I grew up playing and fishing in Big Canoe Creek. I’m grateful for my dad, grandad, and uncle taking me to ‘the creek.’ I’ve watched my girls play in the creek. Hopefully I’m fortunate enough to take my future grandchildren to dip their feet in Big Canoe Creek, just like mine took me.”