Distilling a love and life of music into one store

Story and Photos by Graham Hadley

Window shopping on Cogswell Avenue in Pell City’s historic downtown, anyone with any interest in music will be drawn to Ron Partain’s store.

Following the sound of classic rock from the past four decades piped through speakers in the front of Ron Partain’s World of Music, visitors can look in and see guitars — electric and acoustic, mandolins, keyboards and electric pianos, banjos, amplifiers, drum sets, even a colorful row of ukuleles.

Plus everything else under the sun necessary for people to make music: effects pedals, sound mixing equipment, pics, microphones, speakers, strings, instrument straps and much more. Every inch of Ron Partain’s World of Music is a testament to his love of music.

And that is exactly the way he wants it — for Ron Partain, since his mid teenage years, his life has centered on music — and it’s a love that he wants to share with the world. So he, with the help of long-time employee Karen Poe, distill that love into the store that has been open on Cogswell for 41 years now.

And that is exactly the way he wants it — for Ron Partain, since his mid teenage years, his life has centered on music — and it’s a love that he wants to share with the world. So he, with the help of long-time employee Karen Poe, distill that love into the store that has been open on Cogswell for 41 years now.

The original store was located just down the street from its current location at 1914 Cogswell. Partain, who has spent his life as a music director for various church choirs in St. Clair and Talladega counties, knew he wanted and needed to do more with his life, and a music store seemed the perfect fit. “I loved the choir work, but I had two daughters to get through college. I had to do something — and here we are,” he said.

“I had no real money in 1977 when I decided to do this. I had maybe $1,000 and had to borrow three to four thousand more.”

Everything came together, and Ron Partain’s World of Music opened its doors for the first time across the street from the St. Clair County Courthouse in 1978. The original shop was much smaller than the current one — “a hole in the wall” he called it — and that was a particular issue because, back then, they sold full-size pianos and organs.

But it did the trick, cementing World of Music as a downtown staple for almost half a century.

It was also the beginning of a business relationship and friendship that has lasted almost as long as the business has been around. There were more than one business located in the building Partain bought all those years ago, and one of them was a Sneaky Pete’s restaurant. The owners were looking to sell their business, and Partain took the opportunity to expand his income. Within a few years, someone presented him with an offer to purchase the restaurant that was too good to refuse.

Karen, who was 19 at the time, was the cashier at the restaurant. “I figured I was out of a job,” she said.

Not so. “I handed her the keys to the music store and said, ‘You run the business for a while. I am going to play golf.’” And he did exactly that. Partain confessed he needed some relaxation time. Between his duties as a music director, running the music store and managing a restaurant, he admittedly needed to catch his breath.

“I had no idea what I was doing,” Karen joked. “I spent the first few weeks just stacking and sorting papers so I would look busy.” But she quickly grew into the job of managing the day-to-day operation of World of Music and is still doing so now, 38 years later, something Partain is quick to point out has been a key to the business’ long-term success.

That success should not surprise anyone who knows Partain. At 15, he, like most boys his age, was very focused on sports. Nothing could be further from his mind than music. All that changed when a gentleman named R.U. Green came into the locker room after football practice and announced he was looking for some young men to participate in a concert choir.

Hesitant at first, Partain and a few of the other players realized a choir might be a great place to meet some young ladies. So he joined up, and his life’s path was set.

Hesitant at first, Partain and a few of the other players realized a choir might be a great place to meet some young ladies. So he joined up, and his life’s path was set.

“I had never sung before. By the third or fourth week, I was head of the vocal choir. Music set my heart on fire. I was still 15 when I took my first paying job directing a church choir,” he said, “and I have been doing it ever since. Music just speaks to me.”

And he did get to meet a girl — his wife, in one of the choirs he participated in.

Partain has made a name for himself over the years as a music director, taking choirs, usually groups of high-school students and young college-age adults, all around the globe to perform. They have sung the national anthem at the opening of sporting events in some of the most famous stadiums, like Wrigley Field and the Astro Dome, in the country.

And playing those sports venues has had the added bonus of feeding one of Partain’s other loves — sports. “I got to see Cal Ripken play,” he said.

They also have performed at national monuments, the United Nations, places like the Brooklyn Tabernacle, and been as far away as Hawaii, more than once.

Partain said one of the biggest challenges, other than getting ready to perform before huge crowds, is keeping track of all of the teens and young adults in his group, so they have shirts printed up before each trip that everyone has to wear.

One of Partain’s prized possessions is a quilt made up of the different shirt designs they have used over the years.

“I have gotten to see and do things in my life that I would not have been able to do without music,” he said, adding that one of his proudest achievements is that he got to “sing with my daughters.”

It’s the life that his love of music has given him Partain wants to share with others through his store, which has been in its current location since 1986.

He readily admits, as does Karen, that they can’t play their instruments very well, but that is not the point. “I have a love of music, but I’m not a great musician myself. I love helping other people learn to love music.

“I wanted to give musicians a place in this area to shop,” he said. “I really get my personal fulfilment from watching people, adults and kids, come out here to make music.”

So he took a building and filled it with everything local musicians need. His personal favorites are acoustic guitars — Alvarez in particular. And though he keeps a broad inventory in his store, Partain realizes that to compete with big retailers and the Internet, he needs to have more than what he can fit in one building. He does that by keeping up a network with instrument distributors all over the country and beyond and can order pretty much anything his customers need or want.

But to keep a music store open in a small town, even in an area growing as fast as Pell City, means you have to have something for everyone, and do more than just sell instruments and sound equipment.

Partain says he is probably one of the oldest locally owned retail businesses in the area, and the key has been diversity. They repair instruments, help set up sound systems, even move pianos — if a customer needs an item or needs something done, they find a way to make it happen.

He estimates as many as 75 people a week have taken music lessons at World of Music — from guitar to horns, they can teach it all. They even work with local school bands to keep their instruments in top shape.

As he credits Karen with the success of running the business, Partain says Steven Begley is not only a fantastic music instructor, he can repair almost any instrument.

“We had a guy come in here with his father’s guitar that had gotten water on it. It was all bowed out and warped on the sides, all over.

“Steven took that guitar and worked on it. When the guy came back to pick it up and saw Steven coming out with the completely repaired guitar from the back of the shop, he stopped right here and started crying. He had thought the guitar his father had left him was ruined. Steven made it look like it had never been damaged.”

It is those types of experiences that bring it all home for Partain. “I love sharing music with people. I love everything about this business, talking to people as they come in, the purchasing, the selling — everything.”

And he will share that love with his customers even if you are not looking to buy that day, with people coming by the store just to talk, visit or listen to music.

The doors of Ron Partain’s World of Music are open to musicians and music lovers alike.

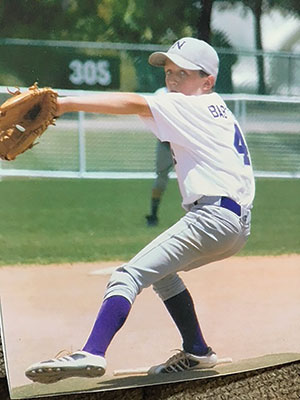

When he was 7, Mize made an announcement to his Mom, Rhonda, that he was going to go to Auburn and play baseball when he grew up.

When he was 7, Mize made an announcement to his Mom, Rhonda, that he was going to go to Auburn and play baseball when he grew up. “He’s so advanced. What makes him advanced is that he commands his better than Olson did. I played with Olson in Baltimore and I played against Tim Hudson. This kid to me is even better. Olson had two pitches; Hudson had three. This kid has four quality pitches. And what I like about him, too, is that he calls his own game. He’s studying hitters already. He’s got a big-league approach already, and he has a big-league workout between starts, too.”

“He’s so advanced. What makes him advanced is that he commands his better than Olson did. I played with Olson in Baltimore and I played against Tim Hudson. This kid to me is even better. Olson had two pitches; Hudson had three. This kid has four quality pitches. And what I like about him, too, is that he calls his own game. He’s studying hitters already. He’s got a big-league approach already, and he has a big-league workout between starts, too.”

Most of the 2,400 square-foot lower level of the house is one large room spanning the width of the metal building. Occupying one end of this Great Room is a fireplace made of Iranian copper that Jim had been saving since the mid-70s. At that time, he was teaching the Shah of Iran how to fly a helicopter, something Jim had been doing since his Army days in Vietnam. “I worked in the Bell Flight School’s secretarial office,” Paulette says. “He had intended to build a bar with that copper, but I wouldn’t let him.”

Most of the 2,400 square-foot lower level of the house is one large room spanning the width of the metal building. Occupying one end of this Great Room is a fireplace made of Iranian copper that Jim had been saving since the mid-70s. At that time, he was teaching the Shah of Iran how to fly a helicopter, something Jim had been doing since his Army days in Vietnam. “I worked in the Bell Flight School’s secretarial office,” Paulette says. “He had intended to build a bar with that copper, but I wouldn’t let him.” What she got was an open-air freight elevator made of gray metal with a wooden floor. A machine shop in Springville built the frame, and its owner, Mickey Dooley, helped Jim install it. Those who don’t like the loud whir of the motor or the open-air feeling while traveling upward can take the stairs, which start as a spiral staircase on one side of the elevator and end as steps on the other side.

What she got was an open-air freight elevator made of gray metal with a wooden floor. A machine shop in Springville built the frame, and its owner, Mickey Dooley, helped Jim install it. Those who don’t like the loud whir of the motor or the open-air feeling while traveling upward can take the stairs, which start as a spiral staircase on one side of the elevator and end as steps on the other side.

The Vandegrifts became leaders in community and church. In 1835, Christopher served as an elder in the organization of Liberty Cumberland Presbyterian Church. In today’s Odenville Presbyterian Church, Christopher’s descendants worship and serve there, continuing the godly influence of their ancestors.

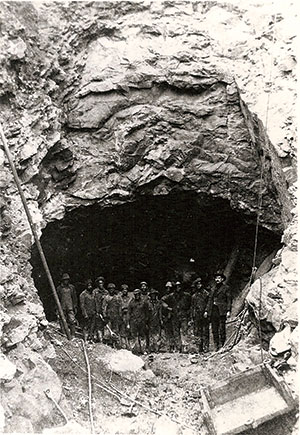

The Vandegrifts became leaders in community and church. In 1835, Christopher served as an elder in the organization of Liberty Cumberland Presbyterian Church. In today’s Odenville Presbyterian Church, Christopher’s descendants worship and serve there, continuing the godly influence of their ancestors. Pickens served in Company C, 18th Infantry Regiment, Confederate States of America. Roland Holcomb recounts a Pickens’ story that happened when the railroad was being put through Odenville very early in the 20th Century. He had given the Seaboard Airline the land and rights to build a tunnel through the mountain as long as the tunnel be called Hardwick and that the train would stop there. Seaboard Airline agreed.

Pickens served in Company C, 18th Infantry Regiment, Confederate States of America. Roland Holcomb recounts a Pickens’ story that happened when the railroad was being put through Odenville very early in the 20th Century. He had given the Seaboard Airline the land and rights to build a tunnel through the mountain as long as the tunnel be called Hardwick and that the train would stop there. Seaboard Airline agreed.

“Compiling ideas was somewhat a labor of love,” says Dave, who was the contractor for the building process that stretched to three years, from planning to move-in in mid-October of 2017. The building of their first home after 11 years together brought to life long-saved ideas. “Yes, there was a wish list,” Dave smiles, “and she got all of it.”

“Compiling ideas was somewhat a labor of love,” says Dave, who was the contractor for the building process that stretched to three years, from planning to move-in in mid-October of 2017. The building of their first home after 11 years together brought to life long-saved ideas. “Yes, there was a wish list,” Dave smiles, “and she got all of it.” The home’s handmade-by-Dave custom items also include the 13-inch curved Cove top molding in the kitchen, lighting fixtures in the great room and several bathrooms that were made from candle holders bought from Hobby Lobby, the candelabra light fixture over the kitchen’s island that is hand crafted with black iron trivets, the full-size bed swing in the middle of the Witches Hat screened area and a cut-stone floor air vent solution between the great room and kitchen.

The home’s handmade-by-Dave custom items also include the 13-inch curved Cove top molding in the kitchen, lighting fixtures in the great room and several bathrooms that were made from candle holders bought from Hobby Lobby, the candelabra light fixture over the kitchen’s island that is hand crafted with black iron trivets, the full-size bed swing in the middle of the Witches Hat screened area and a cut-stone floor air vent solution between the great room and kitchen.

“Bobby got his wish – sort of,” Dollar says.

“Bobby got his wish – sort of,” Dollar says. “You can hear them smile,” Dollar says. “You can hear them cry. You can feel it. It’s palpable. The emotional connection that you have with your audience, you feel it, they feel it.”

“You can hear them smile,” Dollar says. “You can hear them cry. You can feel it. It’s palpable. The emotional connection that you have with your audience, you feel it, they feel it.”