Historian, storyteller, teacher: A life well lived

Story and photos by Jerry C. Smith

Submitted photos

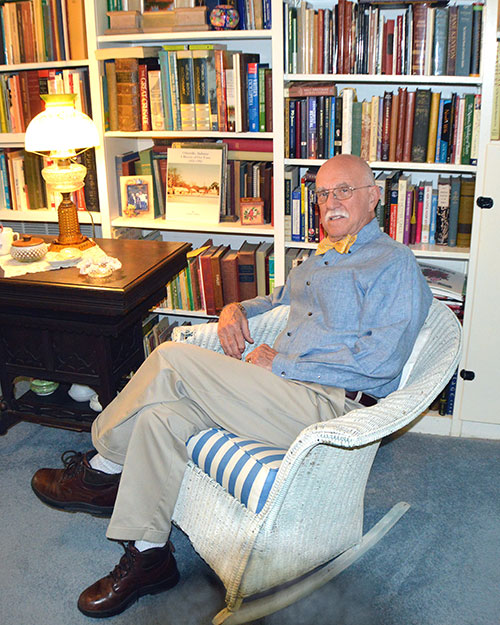

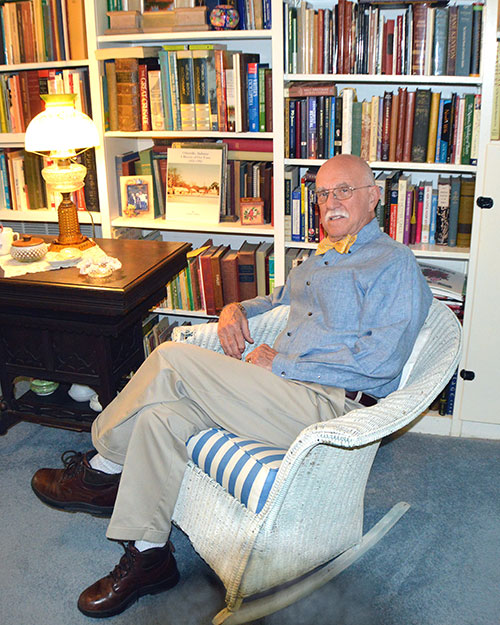

The usual love triangles pale in comparison with Odenville educator and historian Joe Whitten’s quadrangle of passions. In no particular order, they are St. Clair County history, Gail Elaine McGeoch, hundreds of grateful students and the Lord, whom he credits for bringing it all together.

Joe was born in 1938 in Bryant, Alabama, a Jackson County town that dangles near the edge of Sand Mountain, almost in Georgia. His father, Nathan Whitten, died that same year. Joe’s mother, Lorene Hawkins Whitten, remarried four years later to John Armstrong, a teacher and Cumberland Presbyterian minister.

Under his stepfather’s surname, Joe went to Glencoe High School in Etowah County until the 12th-grade, then was sent to Bob Jones Academy in Greenville, South Carolina, to complete high school prior to beginning college at Bob Jones University.

Graduating in 1960, his first degree at Bob Jones was a speech minor in English. While at the Academy, Joe reverted to his birth name of Whitten, as he had never been officially adopted by his stepfather.

Joe’s involuntary exile to Bob Jones became a godsend, for many reasons. Not only did he have his old name back, but he had also escaped a strict household where he’d never been able to make any decisions of his own. “I had a new name, new friends, a new place and never looked back,” he says.

After graduation in 1960, he sought employment suited to his education and ambition, but only succeeded in finding work at a sauerkraut factory in Seattle, Washington, that he wryly defined as “the most miserable job ever.” Vowing to do better, he returned to Bob Jones in 1961 to continue his studies.

This time, he specialized in education courses. After graduation, his mother, who worked at Jacksonville State University, urged him to explore Calhoun and Etowah counties for an entry-level teaching position.

After months of fruitless search, Joe had almost made up his mind to join the Air Force when he got word of an opening in a school that was being built in a tiny burg called Odenville in St. Clair County. He’d heard of the place, but had never been there.

Young teacher hired

At his interview with Principal Dodd Cox, Joe was told that the job was in a new grades 7-12 school currently under construction. “I’ll take it,” he quickly replied. The principal reminded him that he didn’t know a thing about the position and should probably hear the rest of the offer before making up his mind.

Joe says their conversation went something like this:

Principal: “You will be teaching eighth-grade English, ninth-grade English and seventh-grade Math.”

Joe: “I’ll take it.”

Principal: “But wait, the school isn’t even finished yet. …”

Joe: “I’ll take it.”

Principal: “It only pays $350 a month for 10 months a year. …”

Joe: “I’ll take it.”

And thus, on the day after Labor Day in 1961, at age 23, Joseph Whitten began a career that made him a living legend in Odenville education. In all, he taught more than three generations of St. Clair youngsters before retiring at the turn of the century and is a revered guest at every class year reunion.

“Mr. Whitten” was only 5 years older than some of his students, but Mr. Cox insisted his teachers control everything in their classrooms.

Joe relates, “The last thing you wanted to do was take a student out of class and march him to the principal’s office. You took care of it yourself. All us teachers knew it and, more importantly, so did the kids.”

Among his students were those who would one day make a difference in St. Clair County: Sheriff Terry Surles; Coroner Dennis Russell; practically everyone on the Odenville Water Board; Pell City businessman Connie Myers, who would later become principal of St. Clair County High School; and retired teacher Mary Kelley, who taught physical education and health at Odenville before being assigned to the Board of Education, where she served until her retirement in 1999.

“Mr. Whitten was different from any teacher I had ever met,” Mary says. “He was very talented, witty, educated and respected by his students as well as the community of Odenville. As an English teacher, his objective was for students to learn the information and participate in class discussions. These skills worked well – in school and in later life – by providing us with the self-confidence and ability to communicate well with others.”

As the school counselor, Joe’s door was open to students, teachers and support personnel. His professional knowledge provided students with advice and encouragement in the resolution of school and personal issues.

Of his demeanor in class, several respondents agreed that, while Joe was outwardly easy going and gentle, he had ways of getting attention when needed, and everyone knew when to shut up and listen.

Odenville’s Scott Burton tells of his shouting out during an unruly moment in his library class, “Silence, you vile wretches!,” and remembers a sign posted on Mr. Whittten’s desk that fairly warned one and all: CAUTION: DISPOSITION SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE.

Both Mary and Scott said everyone wanted to be in his classes. They found his delivery quite entertaining as he acted out various passages from English literature. He always found ways to make education fun and still managed to help them learn and retain what they’d learned.

According to Scott, Mr. Whitten’s adherence to classroom decorum extended even to paperwork that students turned in. He would not accept sheets torn from a spiral-bound notebook because of their ragged edges, and was known to call kids to the front of the class, hand them scissors and demand they remove those “frizzy” borders. Scott also credits him with being the only English teacher who could make sentence diagramming understandable.

There are enough Mr. Whitten stories told by former students to fill a small book. A local favorite involves one of his Speech classes in which he asked various students to stand and speak on some subject with which they were most familiar.

One boy eagerly volunteered at the beginning of class and took his place at the front of the room. This boy was Odenville’s legendary Slow-Talking John, who was a master at taking forever to tell anything.

His chosen subject was “How To Build A House.” John began by drawing a rectangular set of lines on the blackboard, then said, “This … is … the … footing …,” then proceeded to describe in agonizingly slow, ponderous detail exactly how to dig a foundation wall, pour concrete, etc.

Joe says that by the time John’s house had reached its interior walls, the bell had rung, and he was too numb to do anything but dismiss the class.

While they were sitting on Joe’s front porch some 14 years later, Joe mentioned that day to John, who laughed out loud and explained that the other kids in class had taken up a collection and paid John to speak first so they would not have to recite their own work.

Scott says the one thing that really sticks with him to this day as a result of having Mr. Whitten for a teacher is a deep appreciation for the works of Charles Dickens, Joe’s favorite author. Scott recalls the kids acting out speaking parts while reading Oliver Twist and David Copperfield aloud in class. Scott adds that he would love to do A Christmas Carol today, with Mr. Whitten playing Ebeneezer Scrooge.

The creation of the Odenville/St. Clair County School System is a historical epic in its own right. From its very beginnings in 1864 as a one-room cabin at Hardin’s shop on Springville Road to today’s sprawling campus just east of town, its establishment was an uphill battle all the way.

The school’s history is far too complex to explore here, but the entire saga is neatly summarized in Whitten’s Odenville, Alabama, A History of Our Town 1821-1992.

Many local pioneers and other notables were heavily involved, including entrepreneur Watt T. Brown, Governor Comer and Judge John Inzer. They took special pride in the fact they had beaten Pell City for the honor of having one of the first county high schools in the state.

In 1960, the main building was razed, and a third-generation structure of impressive proportions and excellent design was built. Now grades 1-12 were all on the same campus, divided only by clever architecture. Over the years, he taught English, speech, mathematics, and also served as librarian and counselor for the grammar school. One might feel that Joe and the new school grew up together. As he once remarked, “I wasn’t born in Odenville, but I got here as fast as I could.”

Gail, a love story

A beautiful young lady in Miss Mabe’s Bible class at Bob Jones raised her hand to answer a question. Joe, who was sitting behind her and had wanted to answer first, grabbed her arm to try to lower her hand. This incensed her, and she reminded him in no uncertain terms that this school had a rule against opposite sexes physically touching one another.

A beautiful young lady in Miss Mabe’s Bible class at Bob Jones raised her hand to answer a question. Joe, who was sitting behind her and had wanted to answer first, grabbed her arm to try to lower her hand. This incensed her, and she reminded him in no uncertain terms that this school had a rule against opposite sexes physically touching one another.

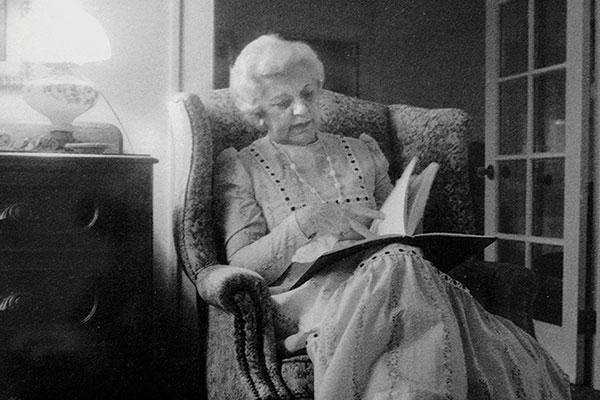

Like many relationships, theirs got off to an unusual start, but Joe Whitten and Gail McGeoch of Cambridge, New York, quickly became friends and remained so for the rest of their stay at Bob Jones. They went their separate ways after Gail’s graduation in 1961.

After eight years of being completely out of touch, Joe received a letter which Gail claimed God had told her to write. She was in Pensacola, Florida, at the time. Joe phoned her, and they talked for nearly three hours. He said the long-distance phone bill was horrendous, but he never regretted paying a penny of it.

They married in 1971, thus beginning a long, beneficent, storybook life together that would warm everyone they met. Gail often defined their marriage as a “strange and wonderful relationship,” always adding, “You’re strange; I’m wonderful.”

Gail and Joe resided in a vintage house built by an Odenville newspaper editor named Luther Maddox. When Joe first came to Odenville, he lived at the Cahaba Hotel, which no longer stands. Later, he boarded with the Bartletts, who lived next door to Maddox. Joe said its restoration was a real challenge, but today it is of museum quality inside and out.

Gail taught school at Ragland for a while, then transferred to Odenville, where she taught in the elementary grades. Her classroom was next to the library where Joe worked at the time.

Gail taught school at Ragland for a while, then transferred to Odenville, where she taught in the elementary grades. Her classroom was next to the library where Joe worked at the time.

Every person I’ve interviewed admires the same things about Gail – her wonderfully warm smile, loving, benign personality and immaculate reputation. The Whittens were very popular with all the students. Together, they were a dream team.

Scott added that Mrs. Whitten loved the snow and always got all excited over the first flake that fell. He also tells a rather amusing story about her coffee habits.

Every day she would make fresh coffee, but first she would carry the pot to an open window on the second floor, holler YOO-HOO, then throw out the old coffee and grounds, never looking to see if anyone was standing below. Everyone quickly learned to avoid that area during morning hours.

Gail played piano and sang in the choir of several churches, as part of a musical family that included Joe on the church organ. Joe praises Gail for proofreading his historical works, and helping to make them the useful volumes they became.

She led an exemplary life, but her greatest moments were yet to come.

Joe, the historian

As if taking scores of St. Clair’s kids under his wing wasn’t enough, Joe also became an educational outlet for the rest of us. If you’re seeking obscure information about almost any historical aspect of St. Clair County, you will sooner or later work with Joe.

Between Joe and recently-retired County Archivist Charlene Simpson, there’s practically nothing one can’t learn about our history. I’ve used both resources for many stories you read in this magazine, as well as my own published works.

Both Charlene and Joe will hasten to say they learned at the hands of veteran chroniclers such as Rubye Hall Edge Sisson (From Trout Creek To Ragland), Mattie Lou Teague Crow (History Of St. Clair County and Diary Of A Confederate Soldier) and Vivian Buffington Qualls (History Of Steele, Alabama).

Joe has published several books of his own, as well as scores of historical society periodicals, papers, meeting minutes and surveys. He worked extensively with the late Garland Minor, who located and annotated hundreds of Civil War burial sites in our area, obtaining markers and other memorials for them.

Joe joined the St. Clair Historical Society shortly after it was formed in the early 1990s by the legendary historian and writer, Mattie Lou Teague Crow, in order to save the historic Looney House from demolition. Joe’s contributions include a nicely-done periodical called Cherish, which is still archived in many local libraries and is an excellent source of research material.

Charlene recalls his frequent visits to her St. Clair County Archives when it was in the Ashville Library building as well as two later locations on the town square. She says Joe was always pleasant, never declined to pause in his own work to help others and added much to the usefulness of that department.

Charlene says his favorite thing was going through archival copies of old St. Clair newspapers, looking for interesting, poignant or just plain funny wedding announcements, epitaphs and other bits of Victorian-era news for his two books, By Murder, Accident & Natural Causes and Wedding Bells &Funeral Knells, both of which are still available.

His first published books were a genealogical study of his Hawkins family, a history of St. Clair High School called Where The Saints Have Trod, a compendium of 18 local church histories called In The Shadow of the Almighty, and the aforementioned Odenville, Alabama – A History of Our Town. All these works still find heavy usage as research materials, especially from St. Clair youngsters working on yearly history projects for a statewide contest with finals in Montgomery.

All his reference works have proper indices, often a large proportion of the book itself. He considers a wasted effort any reference book that is not properly indexed, and totally useless if there’s no index at all.

Joe also serves as a board member for County Archive as well as Odenville’s Fortson Museum. Over the years, he’s donated countless display items and reference works to both places, including a wonderful old foot-pump organ that now graces the Fortson collections.

Joe, the poet

Joe, the poet

One of Joe’s favorite pursuits is writing poetry, particularly oddly-punctuated verse that doesn’t rhyme. He’s an active member of the Alabama State Poetry Society, and his works have fared well in regional contests. He’s printed several chapbooks of his poems, and at one time was the official Poet of the Year of Alabama.

Joe’s love of poetry goes all the way back to his high school days, when he often penned satirical works about his teachers, much to their chagrin and the delight of his fellow students.

One of his proudest possessions is a framed piece of sheet music with one of his poems, Evensong, as its lyrics. Written especially for Joe’s poem, the music got a lot of exposure as part of a Year 2000 millennium project sponsored by the White House Millennium Council and the National Endowment for the Arts. Evensong can be found in Joe’s latest book of poetry, Learning To Tell Time.

Joe takes special pride in helping to connect an American family with a group in France working to erect a memorial to American flyers who had crashed there during World War II. One of those flyers was Richard Smith, whose family had contacted Joe for further information from an obituary he had collected. Smith’s family was invited to France for the dedication ceremony.

Dark clouds gather

A few years ago, Gail was stricken with cancer, marking the beginning of an epic struggle that gave courage to many others who were fighting their own battles. Her unflappable persona remained unchanged for the entire ordeal, always beaming that special smile that could not help but warm those around her.

Her passing in 2010 marked the end of 39 years of an idyllic marriage for Joe and Gail Whitten and brought hundreds into mourning.

Joe says she was cheerful until the very end. He recalls one of their last conversations on the day before her passing, when she was heavily infused with pain medicine and somewhat groggy.

He asked, “Do you know who I am?” She replied sweetly, “Of course I know who you are, Joe.” Some hours later, he leaned over close and whispered a final “I love you.”

Her answer: “I love you, too, whoever you are,” her eyes dancing as she spoke.

Finding peace

Joe says that God moved into their home after Gail passed and has kept him company through his years of loss and resolution. He’s since become involved in mission work to Ecuador as well as extensive world travel and plans to write a few more books.

Perhaps the first stanza of his signature poem, Evensong, tells it best:

The world is quieter now.

Mist rises to mist

and a quietness comes to me

like the quietness of an old house

that whispers long-loved contentment

to past and present.

In Tuscaloosa, he pitched the idea for The Crooners to then program director Roger Duvall. “I loved Sinatra and the crooners, of course, and fortunately, he went for it,” Owen recalled.

In Tuscaloosa, he pitched the idea for The Crooners to then program director Roger Duvall. “I loved Sinatra and the crooners, of course, and fortunately, he went for it,” Owen recalled.

Story and photos by Jerry Smith

Story and photos by Jerry Smith A lover of all things historic, she could not bear to see this fine old structure demolished. Reluctant to put themselves at odds with the indomitable Mrs. Crow, the County Commission agreed that she could have the old building provided she moved it somewhere else, and soon.

A lover of all things historic, she could not bear to see this fine old structure demolished. Reluctant to put themselves at odds with the indomitable Mrs. Crow, the County Commission agreed that she could have the old building provided she moved it somewhere else, and soon.

Preparing for politics

Preparing for politics

In the panic, children piled into the cars of neighbors to get home. Firefighters from as far away as Birmingham, as well as the Alabama National Guard came to fight the blaze, sparked when a train carrying propane exploded. Miraculously, despite the damage to buildings, no one was killed.

In the panic, children piled into the cars of neighbors to get home. Firefighters from as far away as Birmingham, as well as the Alabama National Guard came to fight the blaze, sparked when a train carrying propane exploded. Miraculously, despite the damage to buildings, no one was killed.

“We’re proud of the hills,” said former Coach Mason Dye, who helped former Principal Brian Terry realize his dream of having a cross country track. “It’s a challenging course.”

“We’re proud of the hills,” said former Coach Mason Dye, who helped former Principal Brian Terry realize his dream of having a cross country track. “It’s a challenging course.” When Dye, who also ran track in college, arrived on campus, the course was finished. “He put the vision into play,” Terry said of his young coach.

When Dye, who also ran track in college, arrived on campus, the course was finished. “He put the vision into play,” Terry said of his young coach.

A beautiful young lady in Miss Mabe’s Bible class at Bob Jones raised her hand to answer a question. Joe, who was sitting behind her and had wanted to answer first, grabbed her arm to try to lower her hand. This incensed her, and she reminded him in no uncertain terms that this school had a rule against opposite sexes physically touching one another.

A beautiful young lady in Miss Mabe’s Bible class at Bob Jones raised her hand to answer a question. Joe, who was sitting behind her and had wanted to answer first, grabbed her arm to try to lower her hand. This incensed her, and she reminded him in no uncertain terms that this school had a rule against opposite sexes physically touching one another. Gail taught school at Ragland for a while, then transferred to Odenville, where she taught in the elementary grades. Her classroom was next to the library where Joe worked at the time.

Gail taught school at Ragland for a while, then transferred to Odenville, where she taught in the elementary grades. Her classroom was next to the library where Joe worked at the time. Joe, the poet

Joe, the poet