Fort Strother is long gone, but efforts

continue to preserve the site and its story

Story by Jerry C. Smith

Contributed photos

George Washington never slept in St. Clair County, at least not as far as we know. But Andrew Jackson did, also Davy Crockett and Sam Houston. And, they all slept at a place that has virtually vanished from memory, Fort Strother.

Travelers along Alabama 144 may be familiar with a large stone monument, just west of Neely Henry Dam. It’s inscription reads:

FORT STROTHER

CREEK INDIAN WAR

HEADQUARTERS OF

GENERAL ANDREW JACKSON

1813-1814

It seems such a brief epitaph to represent Fort Strother, a key site in Alabama’s settlement. Incidentally, 2013 is the fort’s 200th anniversary.

Jackson was tasked with solving some rapidly escalating troubles arising from a massacre of Indians by whites at Burnt Corn in south Alabama, and its resulting retaliatory attack by the Red Sticks Creeks. He felt that the only solution was to totally defeat the Creek Nation and remove them from their Southern lands.

Established in 1813 as a military supply depot and operations center, Fort Strother headquartered Andrew Jackson’s Tennessee Militia during the Creek Indian Wars, a local theater of the War of 1812. Jackson had sent his head cartographer, Captain John Strother of the 12th U.S. Infantry, to find the best strategic fort site for conducting military operations against the Creek Indians in Alabama.

Captain Strother’s choice of locations was perfect for receiving supplies overland from the north, loading them onto flatboats built on-site, and floating them down the Coosa for various military operations. It also secured access to a strategic river crossing nearby.

Prior to its construction, the area already hosted a small trading post belonging to Chinnabee, a “friendly” Creek chief. There was also a small Creek village across the river known as Oti Palin (Ten Islands), named for 10 river islands jutting from the river north of the fort site. Ten Islands had become the fording place of choice on that part of the Coosa because of its shallow shoals.

Part of the Tennessee Militia cut a 50-mile road through north Alabama’s wilderness from Fort Deposit to Ten Islands in only six days, and began work on the new encampment. At first called Camp Strother, as the settlement grew and a stockade was built, it became known as Fort Strother.

Part of the Tennessee Militia cut a 50-mile road through north Alabama’s wilderness from Fort Deposit to Ten Islands in only six days, and began work on the new encampment. At first called Camp Strother, as the settlement grew and a stockade was built, it became known as Fort Strother.

On November 1, 1813, Jackson himself arrived from Fort Deposit, and promptly used his Militia to destroy the Creek village of Tallaseehatchee, a few miles across the river. But no sooner had he begun settling in than a call to action came from a most unusual messenger.

Fort Leslie, aka Fort Lashley, was a frontier stronghold of the Leslie family in what is now the city of Talladega. It was besieged by a large number of Red Sticks, a warlike faction of the Creek Nation who were waging vengeful raids against friendly Creeks and settlers that had begun with Fort Mims, a similar family fortress in south Alabama. All within Fort Lashley were surely doomed, awaiting an attack at sunrise the next day.

Among the friendly Creeks within its walls was Selocta Fixico Chinnabee, son of the chief who had begun the settlement at Ten Islands. Selocta knew of the troops at Fort Strother, and devised a clever plan to get their help. He donned the skin of a freshly-killed hog, snuck out of the gate, pretended to be rooting in the underbrush, broke clear undetected and raced to Fort Strother.

The Militia rallied, crossed the Coosa and attacked the unsuspecting Red Sticks at about four in the morning. Jackson’s casualties were minimal, but the Red Sticks were decimated.

Jackson returned to Fort Strother two days later, only to find that vital supplies had not arrived from Fort Deposit. Quoting professional archaeologist Robert Perry’s “LOCATING FORT STROTHER” paper, “With a force of 2,000 men and no food, Jackson’s situation at Fort Strother became desperate. By November 17, Jackson was forced to leave a small contingent of troops at Fort Strother, taking the majority of his force back toward Deposit in search of supplies.

“On December 5, 1813, Jackson had returned to Strother, and on December 9th was forced to put down a mutiny of his volunteers, who insisted that their contracted time had expired.”

By the middle of January 1814, Jackson had solved most of his supply and manpower problems and proceeded from Strother, intending to attack the Red Sticks stronghold at Horseshoe Bend on the Tallapoosa River. However, he was ambushed and nearly overrun in two separate engagements at Emuckfau Creek and Enitachopco Creek.

The mission was a complete failure, and Jackson was forced to retreat to Strother. Perry continues: “The official U.S. Army history of the Creek War characterizes the latter battle as a defeat for Jackson and states, ‘Jackson was compelled to entrench at Fort Strother and remain there for several months.’”

Between January and March of 1814, Jackson employed his troops building boats for transportation of supplies down the Coosa. During this period, the Fort Strother area would have steadily grown in size as the 39th Regiment arrived and Jackson began stockpiling supplies for a Spring offensive. The months of January and February 1814 mark the climax in the history of Fort Strother.

“… The fort had grown into a small city as supplies came in from Fort Deposit and Fort Armstrong. … By March 1814, Jackson had nearly 5,000 men, counting the Indian contingent, … and sufficient supplies for an offensive.”

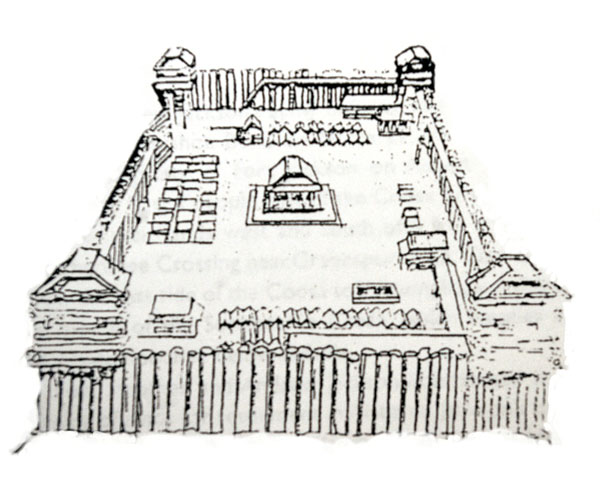

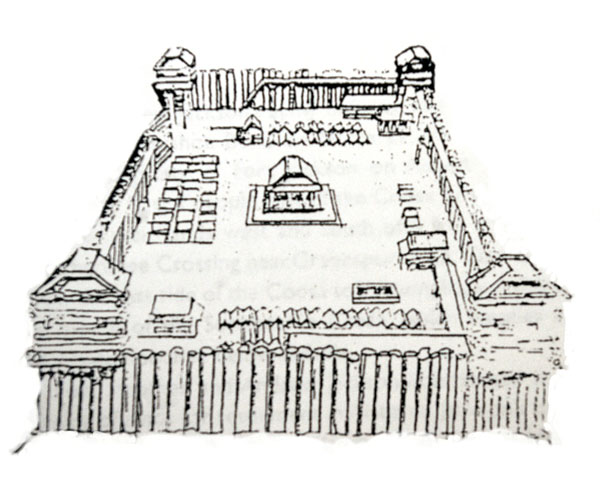

In her History of St. Clair County, AL, Mattie Lou Teague Crow describes the encampment: “The fort, with its blockhouses, three large parade grounds, four separate camps — militia, infantry, cavalry, and at least 300 friendly Indians — was no small enterprise. The Indians — mostly Cherokees, some Creeks — were kept in a group. They wore white feathers and white deer tails to distinguish them from the hostile red men.” Local author Charlotte Hood wrote a book called Jackson’s White Plumes that explores this relationship and the whole Creek campaign.

Crow continues: “At times there were as many as five thousand men at Fort Strother, … and as few as a hundred and fifty. But today, all that is left of the great camp that played such a vital part in Jackson’s campaign is the cemetery, the graves unmarked and forgotten. These men were American soldiers, and they deserve to have their last resting place marked and given the same care as other American military cemeteries.”

Various other writers have surmised there was a fort, blockhouses, blacksmith shops, cooperage, field hospital, corrals for hundreds of horses, quartermaster store, boat-building yard and several wharves along the riverfront.

All these preparations were soon put to use, as described in a National Register of Historic Places application form: “… Jackson had been informed that a large number of Creeks were concentrating at Horseshoe Bend, which they were resolved to defend to the last. Jackson determined to march down the Coosa, establish a new depot, and them march against the Creeks. … On March 14 he departed, leaving 480 men under Col. Steele to hold Fort Strother and keep open lines of communication.

“The subsequent battle … was the decisive battle of the war, breaking the power of the Creek nation, and opening up … two-fifths of what is now Georgia and three-fifths of Alabama for settlement. … Strother continued to be part of a strategic line of communications with the Gulf Coast and Florida, serving as a way-station for troops headed south. No mention of the fort has been found after 1815, when Gen. Coffee and several Indian chiefs conferred there.”

After Horseshoe Bend, Jackson headed southward to Mobile, thence to New Orleans to fight a more famous battle against the British, albeit a wasted one since they were unaware that the War of 1812 had already ended.

And so it also ended for Fort Strother. Folks later traveling the area were totally oblivious to what was there and how important it all was to our lives, and it remains mostly so today. Indeed, walking the overgrown land itself yields no clues of its former usage. But a determined group of St. Clair ladies decided to change all that.

Charlotte Hood, wife of Alabama Power Company hydro manager Jerry Hood; Patsy Hanvey, a Cherokee potter; and Gadsden Library archivist Betty Sue McElroy became known as the Ten Island Three. The APCO newsletter, Powergram, reported on their efforts: “… These three self-taught historians have synthesized information from hundreds of sources, including archives, libraries and fellow history buffs.”

“This information was jumping out at us from all directions,” Patsy says. “We feel just like someone reached out and took us by the hand and led us.”

Their energetic efforts soon bore fruit, and on March 30, 1999, the St. Clair County Commission and the Alabama Historical Commission offered $10,000 each in matching grants for the Fort Strother Survey and Registration Project. In May of that year, a newly formed Fort Strother Restoration Committee met to officially begin work.

Retired Alabama Power executive George Williams had been elected chairman. Project archaeologist Robert Perry was vice chairman, and County Commissioner Jimmy Roberts became project director. Both Roberts and then Congressman Bob Riley played vital roles in obtaining the two $10,000 grants.

Other committee members and newly elected officers were Charles Brannon, vice chairman, also retired from Alabama Power; Carol Maner, historical writer; Rubye Sisson; Harold Sisson; historian Ben Hestley; Calhoun County Commissioner Eli Henderson; Kay Perry, secretary; Adm. Dennis Brooks; Realtor Lyman Lovejoy; Randy Jinks; State Rep. Dave Thomas; newspaper reporter Hervey Folsom; Sherry Bowers; and of course, the indomitable Ten Island Three.

Much exploration was done in the Ten Island environs, including the cutting of fire lanes to simplify field operations. A University of Alabama team led by Carey Oakley and another from Jacksonville State University led by Dr. Harry Holstein located and identified more than 800 artifacts, including gun parts, rifle and musket balls, and iron grapeshot, all consistent with armaments of that era.

Also found were hundreds of wrought-iron spikes and cut nails, assumed to have been used mostly in flatboat-building. Other finds included knife-blade parts, broken iron kettles, various tools, and lots of by-products used in blacksmithing.

However, the finds that would be most dear to Mrs. Crow’s heart were disclosed in the old cemetery. Oakley and his crew used ground-penetrating radar and other modern technologies to locate and catalog some 76 graves adjacent to the assumed stockade site.

But alas, the restoration project ground to a halt when funds ran out. At one time, it was proposed that the old stockade be recreated and the cemetery restored to proper dignity, all in a park-like setting accessible to the public, but that too has fallen by the wayside.

The exact locations of work sites have purposely been left out of this narrative to discourage trespassers and artifact vandals. In fact, all the affected lands are signed and posted. To view the general area, look to the western shore of the Coosa from Alabama 77 near Ohatchee Creek, and let your imagination fill in the rest. One might even visualize Old Hickory himself, on horseback, left arm in a sling from a near-fatal bullet wound suffered in a duel just before coming to Alabama, gazing downriver while making plans for future battles.

It is hoped that someone, or some organization, will resume this important restoration project to bring one of Alabama’s most historic sites to light and make the fort a public part of the state’s heritage.

Some years ago, the Cropwell Historical Society, after great efforts by Mary Mays, George Williams and other members, installed the impressive marker, made from local marble, that is mentioned at the beginning of this story.

Fort Strother has also been honored by a much older, more elaborate marker placed by an Anniston DAR chapter in 1913, on the site’s 100th anniversary. The marker is no longer in sight, but we can still appreciate its words:

Here stood Fort Strother

A defense against the Indians

Built by General Andrew Jackson

And occupied by him and his

Brave men

During the Creek Campaign,

November 3, 1813

Erected by the Frederick Wm. Gray

Chapter DAR of Anniston, Alabama

To preserve the memorial of

Faithful service.

November 13, 1913

By Carol Pappas

By Carol Pappas