Steamboat A-Comin’

Captain Lay raises the bar

Story by Jerry C. Smith

Photos by Jerry C. Smith

Submitted photos

In the two years surrounding the end of the Civil War, Capt. Cummins Lay set a Coosa River record that remains unbroken today; he’s the only river pilot to navigate a steamboat over the Coosa’s entire length, in BOTH directions.

Beginning at the confluence of three smaller streams near Rome, Ga., the Coosa was fairly easy to navigate in the 19th century, at least from Rome to a few miles south of Gadsden. Several rocky shoals and other obstacles had been deepened or cleared with explosives for steamboat traffic, and a thriving river commerce quickly developed between those cities.

But from Greensport to Wetumpka, the Coosa presented a raging maelstrom of rocks and rapids, its bed littered with wreckage and cargo from innumerable keelboats, flatboats, rafts and other crude shallow-river craft of that era. Many who dared to brave the Coosa’s rocks and whitewater shoals never reached their destination.

That section of the Coosa straddles a geological feature called the Fall Line, which separates Alabama’s mountainous northern regions from a much flatter coastal plain. The names of several shoals in that area describe their nature: the Narrows, Devil’s Race, Butting Ram Shoals, Hell’s Gap, and the infamous Devil’s Staircase, which is still a favorite canoeing spot at Wetumpka.

Manufactured goods, agricultural products, timber and passengers flowed freely from northwest Georgia into Etowah, DeKalb, St. Clair, Jefferson and Talladega counties. But the Coosa’s hazardous shallows below Gadsden required unloading all cargo at Greensport, then hauling it by wagon, and later by train, for more than 140 miles before reloading onto other boats at Wetumpka, a costly and tedious detour for shippers. It was in this setting that Captain Lay made his two heroic, record-setting steamboat runs on the Coosa.

In 1864, according to Harvey Jackson’s Rivers of History, Lay escaped from a Union-besieged Rome with two steamboats, the Alpharetta and the Laura Moore. He extinguished their boilers and let them drift silently down river in the night until out of cannon range, then fired them up again and piloted them to Greensport. Vital ship parts and her crew were shielded from small-arms fire by bales of cotton stacked on deck.

Jackson relates, “About the time (Lay) reached Greensport, a late spring storm had hit the valley, and the river was out of its banks. Fearing the Yankees would … follow the Coosa into Alabama, he decided to take advantage of the high water and pilot (his two steamers) farther south, where they would be safe. He moved downstream, ‘high, wide and handsome over inundated cotton and corn fields’ as if the shoals and rapids never existed.”

Lay moored the Alpharetta at Wilsonville, then prepared the Laura Moore for an epic voyage on to Wetumpka using the flooded river to navigate shoals usually floated by only the bravest of boatmen.

Lay moored the Alpharetta at Wilsonville, then prepared the Laura Moore for an epic voyage on to Wetumpka using the flooded river to navigate shoals usually floated by only the bravest of boatmen.

Jackson continues, “Stripping the Laura Moore to make her light as possible, Lay took her into the most dangerous stretch of rapids on the river. Following ‘boat shoots’ (shallow channels) when he could see them and using his river sense when he could not, Cummins Lay guided the Laura Moore around rocks, through channels, and finally over the Devil’s Staircase, whose roar must have drowned out every sound made on board by engines or men.”

After resting in the river pool at Wetumpka, Lay then took his steamer on to Mobile, via the relatively placid Alabama River, where it forms at the confluence of the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers, just south of Wetumpka.

Captain Lay had acted wisely. General Rousseau’s raiders seized Greensport less than a month later, destroying a ferry that had been in service since 1832 and wreaking other wartime ravages that would surely have included Lay’s steamboats. But Lay was not a man to rest upon laurels. In 1866, after the war’s end, he decided to make the same trip, in the same boat, except traveling up river instead of down.

Jackson’s narrative tells us, “… at the foot of Wetumpka Falls, (Lay) waited aboard the recently re-fitted Laura Moore, hoping for water high enough to carry his boat over the rapids to the flat water of the upper Coosa. In spring 1866, the rains came. The river rose and, when it crested, the Laura Moore steamed out into the channel.

“Fighting the current and dodging debris, Lay made it to Greensport and from there had an easy run on into Georgia. … Cummins Lay now held the distinction of being the only captain to make the return trip. Records are usually broken; this one still stands.”

Captain Lay had proven that, given enough water, the Coosa could be navigated by larger commercial craft, rather than the customary flatboats and shallow-draft keelboats. He made it incumbent upon business interests and government to cooperate in making Coosa River navigation a reality.

Lay’s challenge is met

In 1867, U.S. Army Maj. Thomas Pearsall was given the task of surveying the Coosa’s entire length for a navigational feasibility study. Operating on a generous (for that era) $3,000 budget, Pearsall quickly completed his work, although Jackson reports that the last 60 miles, which involved a total drop of more than 275 vertical feet, gave the major’s voyage an exciting white-water finale.

Pearsall recommended no less than 25 locks, using dams to deepen the waters around them. Also proposed was a 50-mile long Coosa-Tennessee River canal from Gadsden to Guntersville. By 1871, this plan had been modified to 31 locks, but the Tennessee canal, which would have added $9.5 million in cost, was dropped.

According to Jackson, “Someone estimated that all this lock and dam work could be accomplished for the sum of $2,340,746.75 – a figure impressive if for no other reason than the certainty of the cents.” If that seems small, consider that in modern money it would be more than $50 million, plus the fact that labor was cheap, plentiful and not subject to OSHA restrictions during those turbulent Reconstruction years.

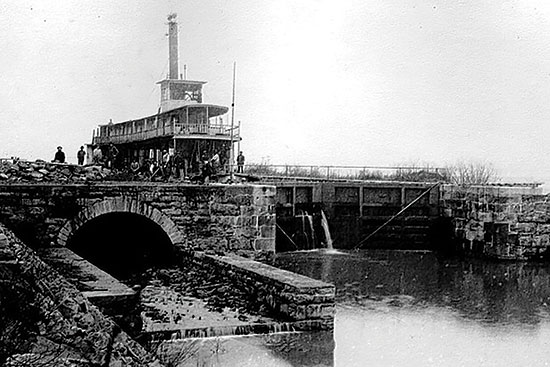

The first three locks were essentially completed in the 1880s. Lock 1 was about a mile downstream from today’s Greensport Marina. Lock 2 lay some three miles farther south, sharing a channel with Lock 3, which was at the south end of Ten Island Shoals, now just below Neely Henry Dam. These three locks, along with various improvements upstream, opened an additional 25 miles of the Coosa to commercial shipping, but various interests lobbied to halt further development in favor of other priorities.

Jackson relates that in 1890, Captain Lay’s son, William Patrick Lay, formed a group of Gadsden businessmen into the Coosa-Alabama River Improvement Association, to champion continuation of the project to its intended goal of a fully-navigable waterway from Rome to the Alabama River, thence to literally any port in the world via Mobile.

Their efforts paid off, at least for a while, as work began on Lock 4 near present-day Lincoln and Riverside, Lock 5 just south of Pell City, and Lock 31 at the base of the rapids in Wetumpka.

Using separate funding, dredges kept the channel reasonably clear while these projects were under way. A 1974 Birmingham News story by Jenna Whitehead describes how Lock 4 took shape: “Mrs. Alice Hudson sold five acres, 4 miles northwest of Lincoln, for the lockhouse and lock. … Barracks were built for some of the workers, some lived on the two (work) boats during the week, some lived at home, some built houses in the area, and others boarded with families in the community.

“Mrs. ’Ma’ Hudson lived east of the dam site and kept a huge barn to board the mules in the wintertime and lean times when funding ran out on the construction. Each lock was equipped with a lockhouse for the keeper, whose job was to raise and lower boats, rafts of wood, launches and to check water levels and temperature.

“Lock 4 was chosen to be the site of the headquarters for the Army Corps of Engineers and was completed in 1890. The building was used for office space and dining area for the workers, but in 1931, when the lock was no longer in use, the property was leased by individuals. In 1964, the lock house became the property of Mr. and Mrs. J.J. Monaghan, who used the building as a home.” William Tuck, who had married Ma Hudson’s daughter, was listed as a lockkeeper.

“Lock 4 was chosen to be the site of the headquarters for the Army Corps of Engineers and was completed in 1890. The building was used for office space and dining area for the workers, but in 1931, when the lock was no longer in use, the property was leased by individuals. In 1964, the lock house became the property of Mr. and Mrs. J.J. Monaghan, who used the building as a home.” William Tuck, who had married Ma Hudson’s daughter, was listed as a lockkeeper.

Regarding construction, Whitehead’s story adds, “Rock for Lock 4 was quarried at Collins Springs, … hand-hewn by local laborers, and brought to the site on railroad cars. Log books at Lock 4 record that in 1892 Lock 4 was navigable but not completed until 1913. Lock 5 was completed and usable, but the dam broke in 1916 and work along the Coosa River ceased.

“Construction of Lock 4 created a community in the area; …stores sprang up, and roads were alive with local wagons hired to bring in brick, wood and stone.”

The Golden Age

With the completion of these dams and locks, the river was open for commerce and pleasure all the way from Rome to the shoals near present-day Logan Martin Dam. Steamboats plied the Coosa regularly, carrying everything from bales of cotton to affluent travelers. It was much like Twain’s Mississippi, except upon much narrower waters.

A newspaper item of that era proclaimed, “The Magnolia is 161 feet long, 26 feet wide and can carry 225 tons of freight. There are 20 splendid staterooms, with new and comfortable bedding. Each berth is carpeted. Her cabin accommodations are superior to those of any boat ever on the Coosa. The bill of fare is not excelled by any hotel in the cities. … The officers on the boat are all clever and affable gentlemen.”

From a treatise, Our Coosa: Its Challenge and Promise: “On the passenger deck sleeping and eating, games and promendar (sic promenade) took place, and the calliope and bands made music for dancing. Goodbyes and welcomes, moonlight rides and romance, the heartbeat of the time was measured in steamboat time.”

These boats’ names usually felt good to the ear; Clifford B. Seay, Magnolia, Alpharetta, Dixie, Cherokee, Hill City, City of Gadsden, Pennington, Coosa, Etowah, Endine, Sydney P. Smith, Dispatch, Clara Belle and Georgia. A steam work boat, originally the Annie M. but later renamed Leota, inspired the popular cartoon strip, “Popeye” (see side story for details).

According to family genealogical data, Greensport had been founded by descendants of pioneer Jacob Green, born in 1767, who came to northern St. Clair around 1820, just after Alabama became a state.

Several generations of Greens created a thriving settlement to take advantage of the necessity of off-loading of freight for land transport to Wetumpka. Eventually, the Evans family joined the Greens by marriage, and their Greensport Marina remains as a marker to a once vibrant village. It was a glamorous age that lasted some 50 years and involved more than 40 different steamboats, but change was again in the wind. It seems W.P. Lay had even bigger ideas for the Coosa.

Putting the Coosa to work

According to John Randolph Hornady’s book, Soldiers of Progress and Industry, John Hall Lipscomb Wood, the landowner at Lock 2, insisted on a permanent flume to provide water power for milling and other purposes. Legend has it that Mr. Lay was so impressed with the power of the water running through this chute that he conceived the idea of harnessing the whole river for hydroelectric power.

Quoting again from Our Coosa, “(Lay) sold his steam plant in Gadsden and built a small hydroelectric plant on Wills Creek, a Coosa tributary near Attalla. In 1906, with capital stock of $5,000, he organized a small corporation, named it Alabama Power Company, and became its first president.” And the rest, as they say, is a whole ’nother story.

Lay never saw his dream come to life. He died in 1940. Lay Dam, the first hydroelectric plant on the Coosa, is named for him.

In a Birmingham News story, Robert Snetzer, of the Army Corps of Engineers and president of W.P. Lay’s Coosa-Alabama Association, said, “… (The locks) were built with federal funding, and with the delays in funding, the riverboat traffic died out. Truck and railway transportation became more economical, thus the work halted between Greensport and the Alabama because it would not prove profitable.”

Nevertheless, the lock system was still in occasional use until the early 1930s, mostly for rafting logs downriver. The last boat to officially pass through the locks was an Army Corps dredge. Many of these structures were dynamited or taken out of service prior to closing spillways on the new hydroelectric dams that formed lakes Logan Martin and Neely Henry.

Among other rising water casualties was Dave Evans Sr.’s ferry at Greensport. Established in 1832 by Jacob Green and later captured by Rousseau’s raiders during the Civil War, Evans operated it until the waters began to rise, using a small skiff with 6 horsepower outboard motor to push the ferry across the river.

He’s quoted in a 1954 Anniston Star story: “Me and my brother have twelve hundred acres here. We figure the whole place will be flooded, so we just plan to move to higher land and go into the fishing business.”

Lock 1 and Lock 2 are now underwater. The sidewalls of Lock 3, just below Henry Dam, are still visible in a former lock channel beside Wood’s Island. Greensport Marina is a Neely Henry landmark. Evans’ son, Dave Evans Jr. is still among the living, strong and wise at age 85.

Of Lock 4, nothing remains except a single wall from the old lock structure and a few hand-hewn rocks from its dam. Lock 5’s ruined dam was never rebuilt, but its remnants lie under 3 to 5 feet of water, near Choccolocco Creek.

However, these abandoned stoneworks are not without their uses.

New life on the river

For many decades, fishermen have found those walls, both before and after impoundment, to be ideal for certain species, such as drum, northern pike and catfish. Pell City resident Fred Bunn tells of going with his father, Frelan “Shot” Bunn, to the old stoneworks at Lock 4, near Riverside.

For many decades, fishermen have found those walls, both before and after impoundment, to be ideal for certain species, such as drum, northern pike and catfish. Pell City resident Fred Bunn tells of going with his father, Frelan “Shot” Bunn, to the old stoneworks at Lock 4, near Riverside.

“Shot” was the manager of a local auto parts store which always closed on Saturday afternoon. A pre-teen at the time, Fred treasures the memory of these father-son fishing trips to Lock 4 and occasionally other lakes, such as Guntersville.

Fred says, “You could catch bream this big (with both hands put together) along with some really huge bass and all the drum you wanted. When the water was down, you could walk across the dam, but we mainly fished off the St. Clair-side bank, where water ran over the dam.”

He adds that there was a bait shop with boat rentals beside the dam, but most folks just bank-fished in the turbulent waters among the rocks.

Riverside resident Jim Trott, now 78, echoes Fred’s recollections, adding that there was once a man who, for 50 cents, would take you in his boat to a big rock near the middle of the dam. Jim also recalls riding across the river on both Dave Evans’ ferry at Greensport and another ferry near the Lock 3 site.

Jim liked to use a long cane pole, baited with crawfish, river mussels, or hellgrammites (Dobson Fly larvae) they had caught in nearby ponds and shoals. He says, “You could literally fill the bed of a pickup truck with drum and catfish, and we did many a time. We hauled them to Gadsden to sell by the pound to people on the street.”

Jim, originally from New Merkle (now Cahaba Heights), often visited the river as a boy, accompanied by an older brother-in-law. About 25 years ago, shortly before retirement, Jim bought a home just downriver from Lock 4. It’s as idyllic as it gets, sitting on a fine, grassy knoll overlooking one of the most scenic coves on the Coosa.

He still frequents the waters around Lock 4, though nothing remains of that structure except a single long wall and a few prime fishing spots known only to Jim’s GPS. But he’s not sharing those with the general public.

Alabama Power Company’s chain of mighty hydroelectric dams and powerhouses helped change the economy and lifestyle of an entire region, but the final Coosa plans did not include navigational locks.

Another speaks of the charter of the local United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1914, and the impoundment of the Coosa in 1946 to form Lake Logan Martin (although this date is a typographical error; should be 1964). A third plaque mentions a cotton gin startup in 1883 and Cropwell Baptist Church in 1889; and the fourth tells of Andrew Jackson’s crossing of the Coosa near Cropwell during the Creek Indian Wars of 1813-14.

Another speaks of the charter of the local United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1914, and the impoundment of the Coosa in 1946 to form Lake Logan Martin (although this date is a typographical error; should be 1964). A third plaque mentions a cotton gin startup in 1883 and Cropwell Baptist Church in 1889; and the fourth tells of Andrew Jackson’s crossing of the Coosa near Cropwell during the Creek Indian Wars of 1813-14.

After its debut in Montgomery in March 2018 at the state’s capitol, it begins in April of 2018 in the City of Moody and Lee and Wilcox counties and continues through November of 2019 en route to all 67 Alabama counties and the official 200th anniversary month of Alabama’s statehood.

After its debut in Montgomery in March 2018 at the state’s capitol, it begins in April of 2018 in the City of Moody and Lee and Wilcox counties and continues through November of 2019 en route to all 67 Alabama counties and the official 200th anniversary month of Alabama’s statehood.

The CHILDREN’S exhibit is an interactive space with rotary phones and their corded touchtone cousins, plus manual typewriters, vintage board games and children’s books. The Preservation Society wanted an area where children could experience things from the past and stay busy while adults tour, Burttram says. The museum plans to continue the “Children’s Day at the Museum” program started last summer by society president Frank Waid, with interactive activities and stories on a summer date to be announced.

The CHILDREN’S exhibit is an interactive space with rotary phones and their corded touchtone cousins, plus manual typewriters, vintage board games and children’s books. The Preservation Society wanted an area where children could experience things from the past and stay busy while adults tour, Burttram says. The museum plans to continue the “Children’s Day at the Museum” program started last summer by society president Frank Waid, with interactive activities and stories on a summer date to be announced.