Alabama’s ‘First Lady’ of flight

Story by Jerry Smith

Story by Jerry Smith

Submitted photos

In 1929, a 9-year-old Birmingham girl named Nancy Batson had a special Christmas wish. She wanted a flight suit, pilot helmet and goggles. The eventual fulfillment of this young lady’s dream of becoming a pilot set a pattern for a lifetime of excitement and service to country, starting during an era when women were expected to have vastly different aspirations.

Born in 1920 to an affluent family in the old Norwood district of Birmingham, Nancy fell in love with aviation at an age when most little girls were still playing with dolls. As a 7-year-old, her parents took her to watch Charles Lindbergh as he walked from a car into Boutwell Auditorium. Nancy was enthralled.

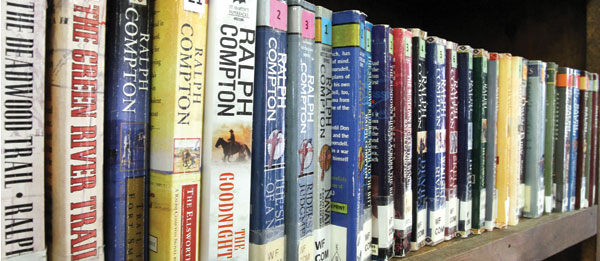

According to Sarah Byrn Rickman in her book, Nancy Batson Crews—Alabama’s First Lady of Flight, Nancy loved to pretend her bicycle was a biplane, imagining it to have wings. Her favorite clothes were jodhpurs, jacket, boots, and a white silk scarf, as worn by all serious aviators of that day. Clearly, Nancy Batson was born to fly, and everyone knew it, including her parents.

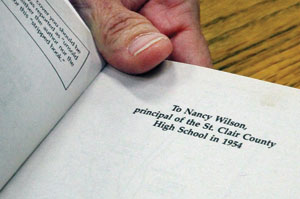

She attended Norwood Elementary, spent her summers at St. Clair’s Camp Winnataska and graduated from Ramsay High School in 1937. Afterward, she attended the University of Alabama, where, in her own words, she “…majored in Southern Belle.” George C. Wallace was a classmate and dance partner. While at UA, she also met Paul Crews, the man whom she would marry several years later.

At the university, she became involved in the Civilian Pilot Training Program. Nancy soloed on March 20, 1940, got her private pilot’s license about three months later and began an aviation career that would earn her a place among the Greatest Generation.

Her father bought her a used Piper J-4 Cub Coupe for about $1,200, instead of another, cheaper J-3 they had looked at which was in really poor condition. In Nancy’s words, “I didn’t ask for that plane. … Daddy decided that that was the airplane he was going to buy me. … I’m 20 years old and a senior in college. Other girls had automobiles. I had an airplane.”

After graduation, Nancy spent a lot of time around Birmingham Airport and joined the newly-formed Civil Air Patrol in 1941. All the while she was flying at every opportunity, building up logbook hours for the future. She got her commercial license in 1942 and began charging people a dollar apiece for rides in her J-4.

After being refused an instructor’s job in a local flight school because she was a woman, Nancy went to Miami and took a job as an airport control tower operator, but quickly became bored with it. She then got an instructor job at Miami’s Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Institute, where she trained Army Air Corps flying cadets. But Nancy wanted to do bigger things with her life.

She heard that a new wartime ferrying operation was being formed that had a women’s squadron. They flew brand-new airplanes from factories all over the country to seaports to be loaded onto ships for the war overseas.

In true Nancy-Batson fashion, she didn’t even wait for a confirmation. She just boarded a train for the group’s headquarters in Wilmington, Delaware, and presented herself to Nancy Love, the squadron’s leader. In Rickman’s words, “Nancy Love watched as a tall, very attractive blonde — dressed in a stylish brown herringbone suit, small matching hat, and brown leather, high-heel pumps — entered her office.”

Within minutes, Love had gotten Nancy accepted and set her up for a physical and flight test the next morning. She easily aced both tests and became a member of WAFS, Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron. Since WAFS was not officially a part of the U.S. military, Love had her girls fitted for uniforms she’d designed herself, although each had to pay for her own.

At first, they ferried PT19 primary trainers and Piper Cubs to training bases. Eventually, the WAFS transitioned to more sophisticated combat aircraft, flying everything from bombers to the mighty P-51 Mustang, the most fearsome fighter plane ever built. There was a name change, too. WAFS became part of WASP, Women Air Force Service Pilots, complete with new blue uniforms.

Most warplanes were designed around male pilots, but the WASP ladies substituted determination for brute strength and made any adjustments necessary to complete their missions. One really petite WASP had a set of wooden blocks made so her feet could reach the rudder pedals.

Several WASPs were lost to training and ferrying accidents, and many more had close calls, including Nancy. She once spent a chilling two hours trying to force a balky nosewheel down on a Lockheed P-38 Lightning that also had engine trouble.

Most planes flown by WASPs were brand new from the factory, their first flight test being the ferry journey itself. These valiant ladies had to deal with really scary, sometimes life-threatening problems on a regular basis.

Most planes flown by WASPs were brand new from the factory, their first flight test being the ferry journey itself. These valiant ladies had to deal with really scary, sometimes life-threatening problems on a regular basis.

According to Rickman, there was no such thing as a schedule. They flew whatever needed flying to wherever it needed to go, often coast-to-coast. There was a war on, and thousands of planes were being built very quickly. Nancy learned and mastered more than 22 military aircraft types, many of them high-performance fighters with more than 2,000 horsepower. One of her advanced instructors was a future U.S. senator, Barry Goldwater.

In spite of all they had done for the war effort, the government still insisted WAFS/WASP was not military and refused any and all benefits, such as insurance, death benefits, hospitalization, pensions, etc. In fact, they were not even accorded an American flag for their casket if they died while serving. Many a bitter Congressional battle was fought over these issues, but WASP remained disenfranchised for the duration of the war. When all was said and done, they were simply told to go home, as if their valiant service had never existed.

Just after a farewell party on their final night on the base, the Officers Club caught fire. They had spent many off-duty hours there during their 27 months of service to WASP. Rickman tells what happened next: “Nancy Batson watched the building go down in flames. She wondered if she was watching her future burn with it. Her passion — her need to fly those hot airplanes — would have to be channeled elsewhere. … A modern-day Scarlett O’Hara, a heroine of a different war and a different time in history, Nancy would think about her future later — when she got home to Alabama.” “Let it burn,” she hollered, and added a rebel yell. “Let it burn!”

Once home, Nancy languished in relatively tame pursuits for a while, not even wanting to fly. She became particularly desolate when a close friend who was serving in China was killed in action while flying his four-engine transport over the “Hump” in Burma (now known as Myanmar).

In 1946, Nancy’s college friend, Paul Crews came home from the war, and they were quietly married in the Batson home. Paul and Nancy lived in several places over the next 15 years. When the Korean War started, Paul, a reservist, went back into service in Gen. Hap Arnold’s brand-new U.S. Air Force. They lived at Warner Robbins airbase in Georgia, then Washington D.C., and finally settled in Anaheim, California, near Disneyland. The Crews also started their family — two sons and a daughter.

Not long after arriving in California, Paul quit the Air Force and joined his former general at Northrop Aviation. Nancy, meanwhile, had not flown a plane in more than 10 years, but after attending a WASP reunion, she found a renewed interest in flying. Finally, after taking a joy ride at Palm Springs Airport, she was reborn as a pilot.

Quoting Rickman: “Though she was a typical 1950s stay-at-home mom when the boys were young, by 1960 that homemaker mantle no longer sat well on her shoulders. Inside, she was still a pursuit pilot. … Her temporarily dormant inner drive was returning. … Nancy knew she was cut out for something more than a domestic life and prowess on the golf course.”

Flying high … again

Once restarted, she pursued her new flying career with a passion. Nancy already had 1,224 hours in her logbook from ferrying military aircraft. She quickly re-earned her elapsed private pilot’s license at a local airport. While building airtime toward advanced ratings, she also flew as copilot in the Powder Puff Derby, a cross-country air race for female pilots. By the end of 1965, she had updated her commercial and certified-flight-instructor ratings. While working as an instructor at Hawthorne Airport, she gave her 14-year-old son Radford his first flying lessons. After returning home later from Vietnam, Rad went on to become a successful commercial pilot.

Paul’s health began to fail during these years, so he took a lesser job at Northrop and began helping Nancy further her own flying career. In 1969, Nancy and Paul bought a new Piper Super-Cub, and she began using it to tow gliders into the air, often as many as 60 a day. “It worked out great,” Nancy said. “I was back in a tail dragger (aircraft with tail wheel instead of nose wheel), and I was in hog heaven.” She flew this plane solo in the 1969 Powder Puff Derby, which ended in Washington D.C. The flyers were invited to the White House to meet the Nixons. While in California, she also mastered glider-flying in her new Schweizer sailplane, often being towed into the air by her own Super Cub.

In 1977, Paul succumbed to complications of diabetes. By 1981, due to a bewildering chain of events and heartaches much too complex to delineate here, Nancy found herself back home in Alabama. Rickman relates, “For Nancy, the move meant starting over. … She was sixty-one years old. … The Alabama she returned to was nothing like the Alabama she had left in 1950. Nancy began to rebuild her life.”

Rebuilding life in Odenville

The Batson family owned a huge tract of farmland near Odenville that had lain idle for many years. Nancy had driven her RV back home to Alabama, crammed with everything she wanted to keep from California. She lived in the RV next to the farmhouse where she and Paul had first lived as a couple, while trying to figure out the best usage of their land.

Nancy joined a real estate firm and got her license. A few of their land holdings were sold to local people so Nancy could concentrate on a huge 80-acre tract that was the main part of their estate left by the death of her parents. She sold her beloved Super Cub to raise enough money to buy out the other heirs, then bought a partly-finished garage structure in foreclosure, right at the edge of the estate property. She moved her RV there while this building was being finished.

After moving into her new home, Nancy sold the RV and began a period of hot-plate and microwave austerity as she worked on what would become her crowning achievement, Lake Country Estates. Using local laborers and craftsmen, she developed one lot at a time. By 1992, Lake Country Estates was thriving.

She dabbled a bit in aviation, hung out with pilot friends and the Birmingham Aero Club and served on the St. Clair Airport Authority. She loved to hangar-bum, and occasionally visited the Four Seasons ultralight flying field at Cool Springs, where this writer first met her. (To my shame, I was still a kid at age 40, and wasted too much valuable time flying my plane rather than chatting with this remarkable lady. And now, some 30 years later, I find myself trying hard to compose a fitting story that could have been mine for the asking back then).

Pilot Ed Stringfellow tells of the time Nancy visited his hangar at Pell City Airport. She had used building materials from Ed’s Mid-South Lumber Company for some of her Estate houses. Shortly after dark, he invited her to go flying with him in his AT-6 trainer, a big, beefy tandem-seater with a powerful radial engine. Ed said, “Here she was, in her late 60s, and hadn’t flown a T-6 since the 1940s, yet she flew loops and other precision maneuvers, in moonlight no less, like she had just done it the day before.” Stringfellow also related a story from the old days, when a future premier Alabama aviator named Joe Shannon was stationed with the Army Air Corps at Key Field in Meridian, Miss.

Nancy had landed there in a twin-engine A-20 bomber she was ferrying to Savannah that needed a few essential repairs. Both Shannon and a mechanic were dazzled when a beautiful, long-haired blonde climbed down from the cockpit. After checking out her plane, Shannon asked the mechanic how long repairs would take. “Depends,“ he replied, “how long do you want her to stay here?”

A lasting legacy

Jim Griffin, director of Southern Museum of Flight, first met Nancy at Pell City Airport.

He had noticed a landing light way off in the distance, heading straight for the airport. This was unusual because the weather was practically unflyable due to high, gusting winds that had grounded everyone else. As the plane got closer, he watched as treacherous gusts threw it all over the sky, its pilot struggling to maintain control.

Despite vicious crosswinds, the Super Cub touched down perfectly, first on one main wheel, then both, exactly as one should land a tail dragger in such conditions. He was amazed when a 60-something lady pilot climbed out of the cockpit. When he praised her great landing under such awful conditions, she replied, “Aw, it wasn’t all that bad.”

Former Pell City Mayor and Judge Bill Hereford remembers Nancy as highly intelligent, yet easy to talk with and full of determination in everything she did. “One of the first things you noticed about Nancy Crews was her steely-gray eyes. They looked right at you and understood everything they saw, and yet she was never intimidating — just an honest, dynamic lady who always knew exactly what she wanted to accomplish.”

Christine Beal-Kaplan, herself a veteran pilot and aircraft mechanic, was one of Nancy’s best friends in St. Clair County. She once drove through Lake Country Estates while telling of some of their adventures while she was helping Nancy put that project together. Although 79 years old, Nancy flew more than 80 hours as co-pilot with Chris on some of her charter runs in a Beechcraft King-Air.

Sadly, Chris passed away recently, taking with her a vast store of anecdotes and memories of Nancy.

On January 14, 2000, Nancy Batson Crews fell into a coma after months of battling cancer and slipped peacefully away at age 80. In Mrs. Rickman’s book, son Paul Crews Jr. said, “She wanted to die in her sleep, and be worth a million dollars. …By the time she died — in her own bed — she was worth more than a million when you figure the land value.” She had indeed fulfilled her own prophecy.

Stringfellow recalls that he and some other pilots were supposed to perform a low, missing-man fly-over pass in Piper Cubs as Nancy was being laid to rest at Elmwood Cemetery, but the fog was almost to ground level, making the flight impossible. However, a huge airliner passed overhead at precisely the right time, making her graveside service complete.

Nancy was inducted into the prestigious Alabama Aviation Hall of Fame in 1989 and the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame in 2004. Birmingham’s Southern Museum of Flight has a display case full of her belongings and memorabilia. Museum director Jim Griffin is particularly proud of that memorial, having known her personally. Nancy had accumulated more than 4,000 hours of flight time in her logbook, which is on display at the museum.

But, perhaps most fitting, wherever vintage pilots or Odenville folks gather to reminisce, sooner or later Nancy Batson Crews’ name will be spoken.

For lots more photos of this amazing woman and her flying career, check out the Discover 2013-January 2014 print and digital edition of Discover St. Clair Magazine.