Capturing the living

moment on her canvas

Story by Elaine Hobson Miller

Photos by Mike Callahan

Submitted photos

One night, artist Joy Varnell was up late watching television when she stumbled upon a show about beach weddings. As the camera panned the California venue, she spotted an artist among the guests, paint brush in hand and canvas on easel. Intrigued, she recorded the show, then played it several more times. Realizing he was painting the wedding scene, she said to herself, “I think I can do that.”

The problem was, she didn’t know how to get started.

That issue was soon resolved when she walked into the home of a friend/client and spotted a wedding invitation on her kitchen counter. “The client mentioned that she wanted to give the wedding couple something unique, and I suggested that I go to the wedding and paint a picture,” Joy said. “She agreed, and when I got back to my car, I thought, ‘What have I done?’ ”

What she did was create a new twist in her artistic career, one that eventually caused her to dump her day job and paint 40 hours a week. She attends weddings and receptions, capturing special moments on canvas. After eight years, that twist has resulted in more than 300 paintings, taken her and her husband all over the United States, and made a lot of brides happy.

Joy started drawing as a child and painting as a teenager. She studied interior designat Southern Institute (which later became Phillips College) and worked as a kitchen designer for 16 years before striking out on her own to do interior design and faux finishes — a lot of faux finishes.

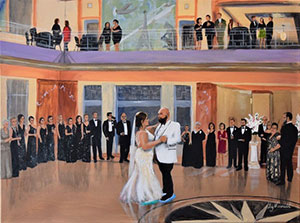

During all those years, she was painting in her spare time and selling her work. Her husband, Tim, kept encouraging her to spend more hours at her easel. Then came that first wedding, a huge event at the Birmingham Museum of Art. She painted the bridal couple descending the stairs for the reception, and in a newspaper article about the wedding, the bridegroom mentioned that her painting was his favorite gift. From there, her new venture took wings.

“This got bigger and bigger and just took over, and I quit doing interior design,” she said. The transition from landscapes, pet portraits and still life to painting people was a struggle at first, but Joy has a knack for looking at something and being able to paint it. Soon, she was painting weekdays and attending one or two weddings on the weekends. Now, it’s a full-time business. “I did 48 paintings in 2018,” said Joy, who calls herself a “live-event artist.”

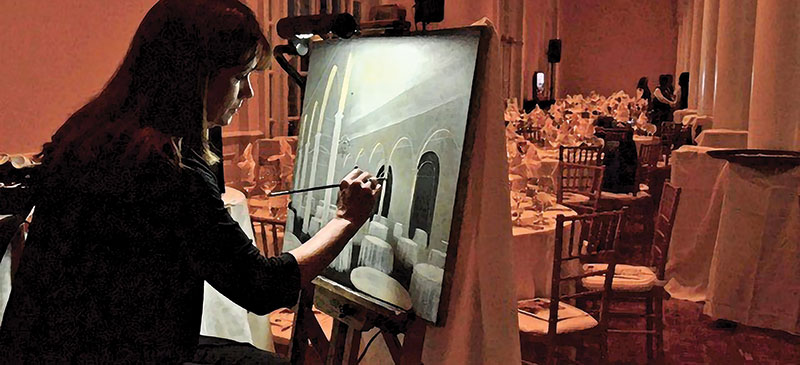

Her modus operandi is to show up about three hours before the event, usually wearing a black dress or pants, to start painting the background. “The vendors usually dress in black, so I do, too,” she explained. The most popular request is to capture the bride and groom’s first dance, so she usually sets up at the reception. When the guests come in, she’s ready to paint them into the scene. When the wedding couple appears, she adds them to the painting.

She tries to get a good likeness of the bride and groom, but not the people in the background. Most of them can be recognized by what they’re wearing. She uses the term, “most,” but brides and their mothers are much more specific than that. “The details of the people in the painting are amazing,” said Pamela Rhodes, mother of a bride who married in Addis, Louisiana. “Joy painted my daughter and son-in-law’s first dance as husband and wife (Peyton and Sean Forestier). We are able to identify every person painted, even the guy singing on the stage (my brother-in-law).”

“The Creator of the Universe certainly shines through Joy’s hand,” gushed Jurrita Williams Louie of Dallas, Texas, who got married in Tuscaloosa, her and her husband’s hometown. “She captured our first dance as Mr. and Mrs. Calvin Louie as if God came down from heaven to earth to do it. I can’t quite get over the detail and thoughtfulness with each stroke.”

Joy’s medium is acrylicsbecause they have no odor and dry quickly. “I have to work very fast, so at least the couple can see themselves before they leave,” she said. “People come up and say, ‘It looks just like them,’ as if they are surprised. Well, that’s the point.” As for mistakes, she just paints over them.

At the time she started, she found only four artists doing what she does. Three were in California, one in New York. There are many more now, but she believes the examples on her website, joyvarnellart.com, and her willingness to travel make her stand out. Her new business has taken her to California, New York, Indiana, Florida, Louisiana and along the Gulf Coast, Georgia and up and down the East Coast as well.

“I average about 12-15 weddings around the New Orleans area and south Louisiana each year,” she said. One such event took place at the restored art deco Lakefront Airport terminal in New Orleans. “It was my daughter, Celeste’s, wedding to Don Jude,” said Claudine Hope’Perret. “It was their first dance, and the painting shows amazing work and detail, even down to their lit-up tennis shoes.”

No one has ever expressed a dislike of her paintings, though she did have a girl ask her to re-do the groom’s hair once. “I strive very hard to get what they want,” she said.

Tim, who is retired from the Norfolk Southern Railroad, goes to the weddings with Joy and does most of the driving. Anything over 500 miles, they fly. He packs up her paints and tools at home, unpacks and sets up at the venue, then repacks. “He calls himself my roadie,” she said. “He’s my public relations man, too. He mingles.”

Some of the brides are nervous, and others just very excited and enjoying their day. The grooms are always nervous, and usually say, “Where do you want me?” Kids just stand and stare.

The most common request she gets while painting is, “Will you take 10 (or 20) pounds off me?” That often comes from the mother of the bride. “Sometimes a woman will come up and talk to me because she’s afraid to talk to Joy,” Tim said. “One woman asked if Joy would take off her stomach and give her some boobs.” A man might ask her to cover a bald spot.

Sometimes Joy adds details that represent something meaningful to the couple. Once, she painted a map rolled out to represent a treasure hunt, because that’s how the groom led the bride to her ring and his proposal. She has painted favorite dogs, relatives who couldn’t attend, even dead relatives into the paintings. She has put cats in, too. “Very often the venue will have one, and I’ll paint it peeping through a window,” she said. Occasionally she’ll give the bride a brush and let her paint a few strokes of her own.

She has painted outdoors in all types of weather, from 35-degree temperatures on New Year’s Eve to 95-degrees in the sun. She prefers the reception to the ceremony because it’s less structured, and she gets to interact with the people. “That’s part of what makes it fun,” she said.

One of her most memorable events was a Hindu wedding in Indiana. The bride wanted her to paint the Seven Vows, but she didn’t know what they were or where they occurred in the ceremony, which was four hours long. She kept asking people, and no one seemed to know. Parts of the ceremony were in English, parts in Hindi, and it turned out that the Seven Vows were at the end. Tim found out and clued her in.

An outdoor wedding in Biloxi,Mississippi, was notable because a storm came up and sent many guests inside. The bridal party remained outside, and at the end of ceremony, the couple was framed by a rainbow.

There was one in Fort Deposit they’ll never forget, either, but for a very different reason. “When we got out of the car there, we realized we had left my paints at home,” Joy recalled. They carry an emergency set, which has been upgraded as a result of that trip.

She hates having to tell people she is already booked for their special date, and has painted two events in one day, as much as 90 miles apart. One time, she got two separate bookings for the same wedding, at Aldridge Gardens in Hoover. “The bride’s mother had contacted me and asked for a painting of the couple’s first dance,” she said. “Then I got another request for the same wedding. The bride wanted one of the father-daughter dance to give to her parents. Neither knew about the other’s request.” She had two canvases on her easel throughout the reception and kept swapping them back and forth so neither party would know about the other. The backgrounds were the same. “The bride’s mother began to catch on, but the dad never did,” Joy said. “I presented both paintings at the end.”

Sometimes she finishes a painting on site but brings home most of them so she can apply an art varnish as a protective sealer. Her studio is a sunny 11’ x1 2’ room of her house, with a huge front-facing window. She and Tim have lived in that house on a mountain top in Springville for 12 years, surrounded by rock formations, trees and lots of wildlife. Deer and turkey wander around the property, along with a family of foxes that they feed daily. The house is filled with Joy’s still-life paintings, such as wine bottles so real you want to grab one and pour a drink.

Jessica Silvers Posey of Maryland, who married Aaron Posey in Laurel, Delaware, said Joy painted the most beautiful picture of the couple’s first dance. “The details are phenomenal,” she said. “I relive that moment every time I look at the painting. Everyone who walks past this painting in our house can’t help but stop and stare.”

While mothers, parents, bridesmaids, co-workers and grooms hire her to paint as a gift, most of the time it’s the brides who engage her services.

She offers three standard sizes, 18” x 24”, 24” x 30” and 30” x 36”. Clients may choose something larger but cannot choose whether the finished product will be vertical or horizontal. “I decide that, depending upon the venue and what I want to get in the painting,” Joy said. The largest one she has done was 42” x 48”. Her prices start at $1,000, plus travel expenses if she goes outside the Birmingham Metro area.

Although 99 percent of her business comes from weddings, she has painted at Christmas parties, company anniversaries and fundraisers. One of her corporate events was the opening of Nick Saban’s Mercedes-Benz dealership on I-459. And yes, the coach was there.

Even though she doesn’t normally turn down an event unless she is already booked, she did refuse to paint at one recent wedding. Her own daughter was the bride, the wedding took place at Joy and Tim’s house, and Joy wanted to relax as much as possible and enjoy it.

“I will paint it later from photographs,” she said.

“This got bigger and bigger and just took over, and I quit doing interior design,” she said. The transition from landscapes, pet portraits and still life to painting people was a struggle at first, but Joy has a knack for looking at something and being able to paint it. Soon, she was painting weekdays and attending one or two weddings on the weekends. Now, it’s a full-time business. “I did 48 paintings in 2018,” said Joy, who calls herself a “live-event artist.”

Her modus operandi is to show up about three hours before the event, usually wearing a black dress or pants, to start painting the background. “The vendors usually dress in black, so I do, too,” she explained. The most popular request is to capture the bride and groom’s first dance, so she usually sets up at the reception. When the guests come in, she’s ready to paint them into the scene. When the wedding couple appears, she adds them to the painting.

She tries to get a good likeness of the bride and groom, but not the people in the background. Most of them can be recognized by what they’re wearing. She uses the term, “most,” but brides and their mothers are much more specific than that. “The details of the people in the painting are amazing,” said Pamela Rhodes, mother of a bride who married in Addis, Louisiana. “Joy painted my daughter and son-in-law’s first dance as husband and wife (Peyton and Sean Forestier). We are able to identify every person painted, even the guy singing on the stage (my brother-in-law).”

“The Creator of the Universe certainly shines through Joy’s hand,” gushed Jurrita Williams Louie of Dallas, Texas, who got married in Tuscaloosa, her and her husband’s hometown. “She captured our first dance as Mr. and Mrs. Calvin Louie as if God came down from heaven to earth to do it. I can’t quite get over the detail and thoughtfulness with each stroke.”

Joy’s medium is acrylicsbecause they have no odor and dry quickly. “I have to work very fast, so at least the couple can see themselves before they leave,” she said. “People come up and say, ‘It looks just like them,’ as if they are surprised. Well, that’s the point.” As for mistakes, she just paints over them.

At the time she started, she found only four artists doing what she does. Three were in California, one in New York. There are many more now, but she believes the examples on her website, joyvarnellart.com, and her willingness to travel make her stand out. Her new business has taken her to California, New York, Indiana, Florida, Louisiana and along the Gulf Coast, Georgia and up and down the East Coast as well.

“I average about 12-15 weddings around the New Orleans area and south Louisiana each year,” she said. One such event took place at the restored art deco Lakefront Airport terminal in New Orleans. “It was my daughter, Celeste’s, wedding to Don Jude,” said Claudine Hope’Perret. “It was their first dance, and the painting shows amazing work and detail, even down to their lit-up tennis shoes.”

No one has ever expressed a dislike of her paintings, though she did have a girl ask her to re-do the groom’s hair once. “I strive very hard to get what they want,” she said.

Tim, who is retired from the Norfolk Southern Railroad, goes to the weddings with Joy and does most of the driving. Anything over 500 miles, they fly. He packs up her paints and tools at home, unpacks and sets up at the venue, then repacks. “He calls himself my roadie,” she said. “He’s my public relations man, too. He mingles.”

Some of the brides are nervous, and others just very excited and enjoying their day. The grooms are always nervous, and usually say, “Where do you want me?” Kids just stand and stare.

The most common request she gets while painting is, “Will you take 10 (or 20) pounds off me?” That often comes from the mother of the bride. “Sometimes a woman will come up and talk to me because she’s afraid to talk to Joy,” Tim said. “One woman asked if Joy would take off her stomach and give her some boobs.” A man might ask her to cover a bald spot.

Sometimes Joy adds details that represent something meaningful to the couple. Once, she painted a map rolled out to represent a treasure hunt, because that’s how the groom led the bride to her ring and his proposal. She has painted favorite dogs, relatives who couldn’t attend, even dead relatives into the paintings. She has put cats in, too. “Very often the venue will have one, and I’ll paint it peeping through a window,” she said. Occasionally she’ll give the bride a brush and let her paint a few strokes of her own.

She has painted outdoors in all types of weather, from 35-degree temperatures on New Year’s Eve to 95-degrees in the sun. She prefers the reception to the ceremony because it’s less structured, and she gets to interact with the people. “That’s part of what makes it fun,” she said.

One of her most memorable events was a Hindu wedding in Indiana. The bride wanted her to paint the Seven Vows, but she didn’t know what they were or where they occurred in the ceremony, which was four hours long. She kept asking people, and no one seemed to know. Parts of the ceremony were in English, parts in Hindi, and it turned out that the Seven Vows were at the end. Tim found out and clued her in.

An outdoor wedding in Biloxi,Mississippi, was notable because a storm came up and sent many guests inside. The bridal party remained outside, and at the end of ceremony, the couple was framed by a rainbow.

There was one in Fort Deposit they’ll never forget, either, but for a very different reason. “When we got out of the car there, we realized we had left my paints at home,” Joy recalled. They carry an emergency set, which has been upgraded as a result of that trip.

She hates having to tell people she is already booked for their special date, and has painted two events in one day, as much as 90 miles apart. One time, she got two separate bookings for the same wedding, at Aldridge Gardens in Hoover. “The bride’s mother had contacted me and asked for a painting of the couple’s first dance,” she said. “Then I got another request for the same wedding. The bride wanted one of the father-daughter dance to give to her parents. Neither knew about the other’s request.” She had two canvases on her easel throughout the reception and kept swapping them back and forth so neither party would know about the other. The backgrounds were the same. “The bride’s mother began to catch on, but the dad never did,” Joy said. “I presented both paintings at the end.”

Sometimes she finishes a painting on site but brings home most of them so she can apply an art varnish as a protective sealer. Her studio is a sunny 11’ x1 2’ room of her house, with a huge front-facing window. She and Tim have lived in that house on a mountain top in Springville for 12 years, surrounded by rock formations, trees and lots of wildlife. Deer and turkey wander around the property, along with a family of foxes that they feed daily. The house is filled with Joy’s still-life paintings, such as wine bottles so real you want to grab one and pour a drink.

Jessica Silvers Posey of Maryland, who married Aaron Posey in Laurel, Delaware, said Joy painted the most beautiful picture of the couple’s first dance. “The details are phenomenal,” she said. “I relive that moment every time I look at the painting. Everyone who walks past this painting in our house can’t help but stop and stare.”

While mothers, parents, bridesmaids, co-workers and grooms hire her to paint as a gift, most of the time it’s the brides who engage her services.

She offers three standard sizes, 18” x 24”, 24” x 30” and 30” x 36”. Clients may choose something larger but cannot choose whether the finished product will be vertical or horizontal. “I decide that, depending upon the venue and what I want to get in the painting,” Joy said. The largest one she has done was 42” x 48”. Her prices start at $1,000, plus travel expenses if she goes outside the Birmingham Metro area.

Although 99 percent of her business comes from weddings, she has painted at Christmas parties, company anniversaries and fundraisers. One of her corporate events was the opening of Nick Saban’s Mercedes-Benz dealership on I-459. And yes, the coach was there.

Even though she doesn’t normally turn down an event unless she is already booked, she did refuse to paint at one recent wedding. Her own daughter was the bride, the wedding took place at Joy and Tim’s house, and Joy wanted to relax as much as possible and enjoy it. “I will paint it later from photographs,” she said.

She would visit five continents; meet Rock Hudson, Clint Eastwood, Bob Hope, Lucille Ball and a legion of other stars; be part of a “Ben Casey” rehearsal; and lunch with Dustin Hoffman’s parents. She would even have to use her acting skills and an exaggerated Southern accent to talk her way out of trouble with President Richard Nixon’s Secret Service detail.

She would visit five continents; meet Rock Hudson, Clint Eastwood, Bob Hope, Lucille Ball and a legion of other stars; be part of a “Ben Casey” rehearsal; and lunch with Dustin Hoffman’s parents. She would even have to use her acting skills and an exaggerated Southern accent to talk her way out of trouble with President Richard Nixon’s Secret Service detail. When Emmett completed his military service in 1953, he became entertainment editor at the Birmingham Post-Herald. Bobbye taught music at Saks Junior High School. The two also attended Birmingham-Southern College – Emmett to do his master’s coursework, and Bobbye to finish her degrees in English and Spanish.

When Emmett completed his military service in 1953, he became entertainment editor at the Birmingham Post-Herald. Bobbye taught music at Saks Junior High School. The two also attended Birmingham-Southern College – Emmett to do his master’s coursework, and Bobbye to finish her degrees in English and Spanish.

Once his protective gear is on – a helmet and vest mandated by the MBR (Mini Bull Riders Association) – he’s unflappable.

Once his protective gear is on – a helmet and vest mandated by the MBR (Mini Bull Riders Association) – he’s unflappable. At only 12, Carpenetti has drawn comparisons to the late Lane Frost. Frost, who won the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA) Bull Riding World Championship in 1987 when he was just 24, was killed in the arena in 1989. To this day, long after his death, Frost casts an almost mythic shadow over the sport.

At only 12, Carpenetti has drawn comparisons to the late Lane Frost. Frost, who won the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA) Bull Riding World Championship in 1987 when he was just 24, was killed in the arena in 1989. To this day, long after his death, Frost casts an almost mythic shadow over the sport.

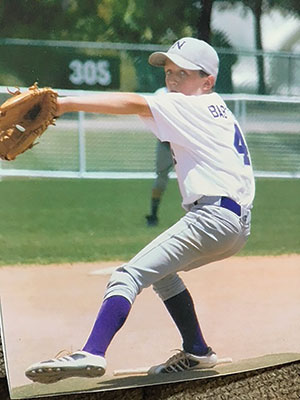

When he was 7, Mize made an announcement to his Mom, Rhonda, that he was going to go to Auburn and play baseball when he grew up.

When he was 7, Mize made an announcement to his Mom, Rhonda, that he was going to go to Auburn and play baseball when he grew up. “He’s so advanced. What makes him advanced is that he commands his better than Olson did. I played with Olson in Baltimore and I played against Tim Hudson. This kid to me is even better. Olson had two pitches; Hudson had three. This kid has four quality pitches. And what I like about him, too, is that he calls his own game. He’s studying hitters already. He’s got a big-league approach already, and he has a big-league workout between starts, too.”

“He’s so advanced. What makes him advanced is that he commands his better than Olson did. I played with Olson in Baltimore and I played against Tim Hudson. This kid to me is even better. Olson had two pitches; Hudson had three. This kid has four quality pitches. And what I like about him, too, is that he calls his own game. He’s studying hitters already. He’s got a big-league approach already, and he has a big-league workout between starts, too.”