Revealing the Beauty Within

Story by Roxann Edsall

Photos by Mackenzie Free

Eric Knepper doesn’t take credit for the beauty in his work. A profoundly spiritual man, he says he’s simply revealing the beauty that is already within the wood when he carves his one-of-a-kind pieces.

“You just get inside the piece of wood and see what God made,” says the artisan. “That’s what you want to show, all the beauty in the grains.”

For nearly three decades, Knepper has been unveiling the natural beauty in the wood around him and crafting hundreds of pieces of original wood treasures. An old rotten maple tree found new life as a beautiful bowl. A red oak tree that had to be cut on his property was transformed into a rolltop desk, a credenza and a file cabinet.

His wife, Pat, smiles across the table as she talks about different items he has created over the years. The house is filled with them, from the dining room’s exquisitely carved grandfather clock with cabriole legs to the stunning freestanding cabinet in the living room made from pieces of an old fireplace screen. “He is so talented. I can’t think of anything I’ve asked Eric to do that he hasn’t been able to do,” she adds, her eyes filled with pride. “He will find a way to do anything.”

The son of a carpenter, and a very determined man himself, Knepper made furniture early in his marriage to meet the needs of his family. “When you get started, you have nothing. We built things then because you couldn’t afford them,” he explains. He even did all the millwork in the home that they built in 1997. But it wasn’t until after retirement at age 60 that his woodworking expanded into a new passion – wood carving.

On a camping trip the couple took to Florida, his interest in carving came alive. “People in the campsite next to us carved, and he took me to a carving club in Fort Myers.” When Knepper returned to Pell City, he met with Tom Goodwin, a carver from a local carving club, and the two became great friends.

Goodwin took Knepper under his wing, showing him how to work with different woods and specific tools. His friend has since passed, but Knepper still has the carving equipment that once belonged to Goodwin. After revealing that he was terminally ill, Goodwin asked Knepper to buy his carving tools so he could pass them on to someone with a passion for the art.

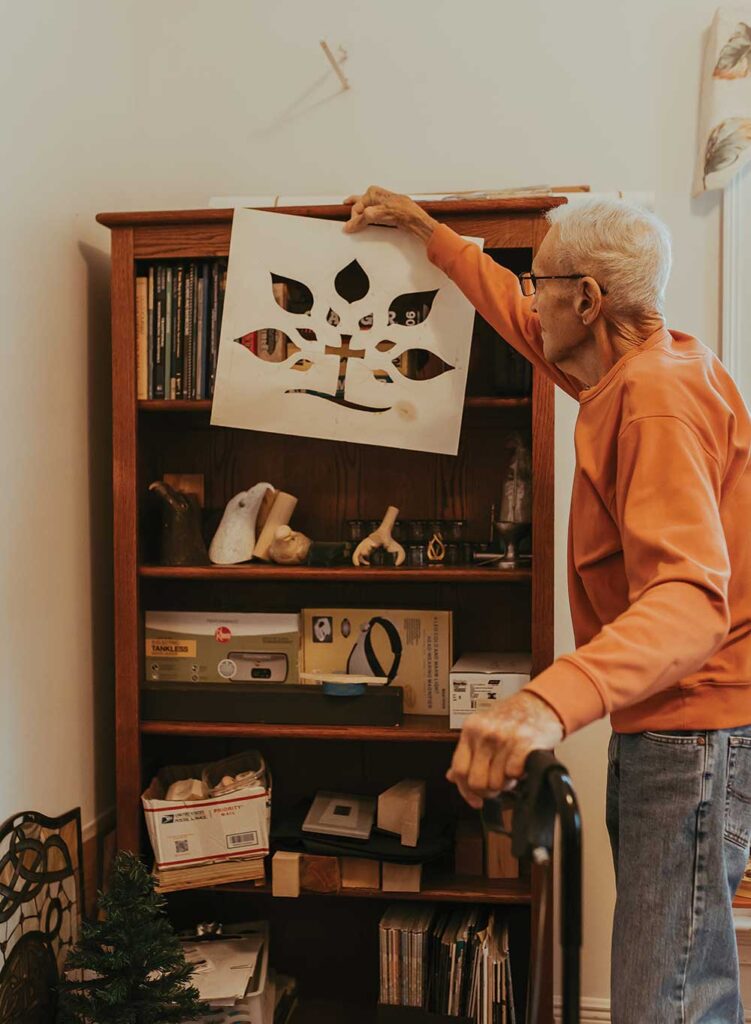

Those specialty tools, Knepper explains, are mostly different chisels and knives, with some power carving tools. “On a given project, you might use two or three tools primarily, or for furniture, (you might use) your whole shop,” Knepper says. He has a wood carving room within the house for smaller projects. Larger pieces are handled in his wood shop in the barn.

As any wood carver would tell you, keeping your tools sharp is essential. Keeping them sharp is important for precise cuts, but it can also create the need for some emergency care, as was the case for Knepper seven years ago. “I cut the end of my thumb off about 6 years ago,” he admits. “You don’t even notice it now. I don’t even remember what I was working on, but I did a dumb thing.”

“He just came in and said he needed a band aid,” tells Pat. He needed a bit more than that. “It was hard to get it to fit back together,” she adds, giving credit to “a wonderful nurse practitioner at Dr. Helms’ office.”

The Kneppers handled the crisis with the same grace and perseverance that has defined their 63 years of marriage. The two met while Eric was in the Navy in Virginia. Moves to Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Illinois and Indiana preceded their final landing in Pell City where he came to work at National Cement. He later left that company and bought Pell City Fabrication, which provided maintenance and support for steel fabrication and other industries.

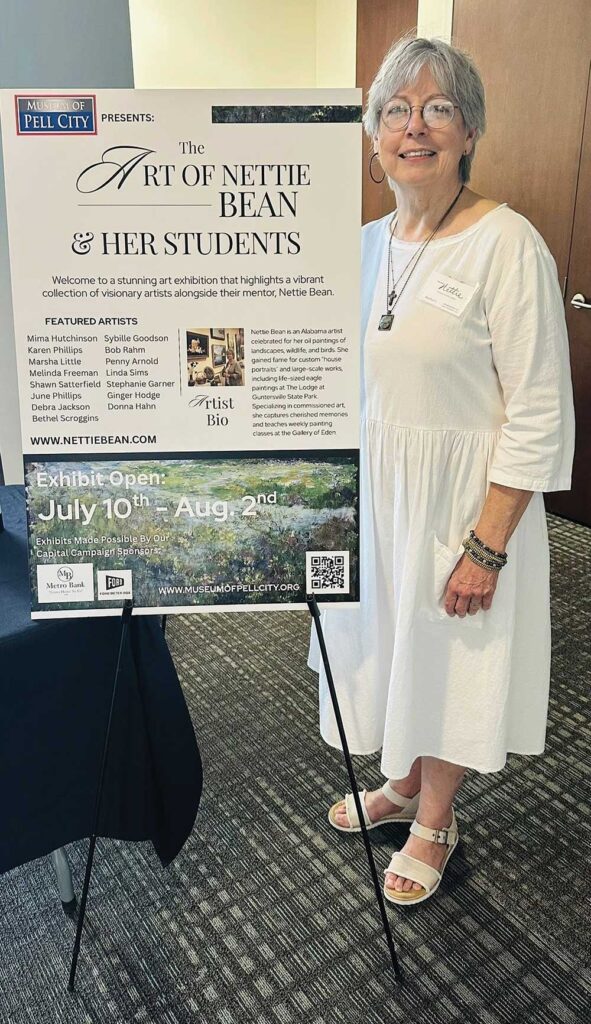

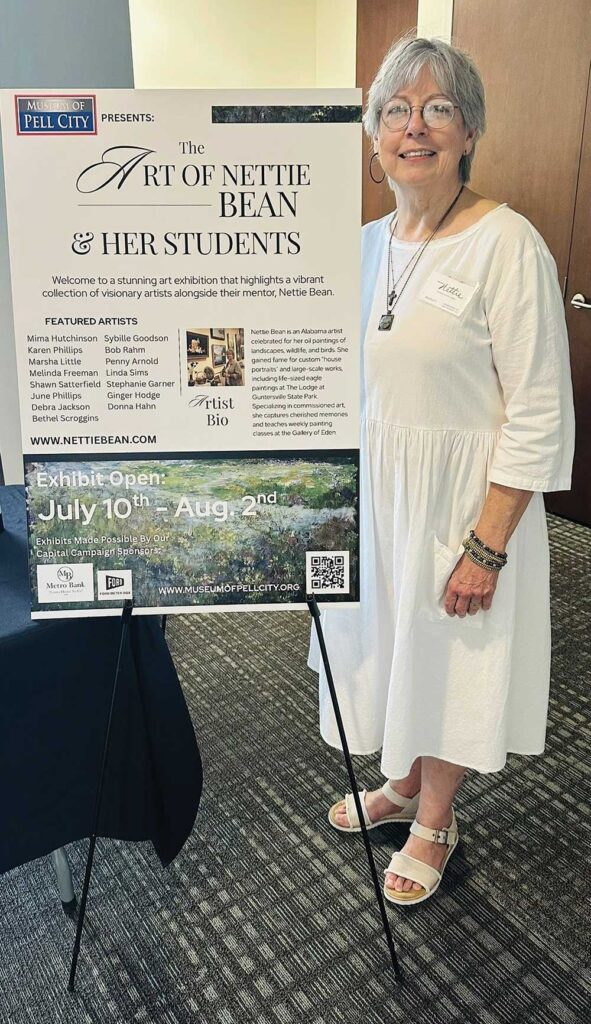

The couple have three grown children (Shawn, Scott, and Ericka), eight grandchildren, and five great grandchildren. Knepper says he sees talent in each of them and potentially at least one future wood carver. Several family members were among the guests at a recent art exhibit at the Pell City Museum of Art featuring his wood carvings.

Knepper’s most challenging piece was among that collection of works. He describes it as a “gold spiral thing,” for lack of a more technical term. “I just saw a picture of it and decided to give it a try,” he says. “It was very difficult because it’s hollow. I had to work from the inside out.”

The art of carving is an ongoing lesson in patience and finesse. Knepper also stresses the importance of listening to the wood. “The wood will tell you what to do, basically.” He considers himself less of a designer and more of a collaborator, with each knot, grain and imperfection guiding his hands. The character of the wood, with its texture and color, add to the direction the project takes.

Knepper has done much of his work from wood that has fallen on his property or that others have brought to him. Oak and Cherry woods are favorites, but he also has done many projects with Cottonwood and other bark woods. “I really like the color and grain of cherry,” he adds. “Sometimes people bring me roots they’ve dug up. It looks terrible, but I cut it up and look inside and it’s beautiful. You just never know.”

Though he finds it difficult to choose a favorite, some pieces – like a beer bottle complete with a bear in a Paul “Bear” Bryant houndstooth hat – clearly delight Knepper. Throughout his home, bowls, spiral works, vases and boxes crafted by this modest woodcarver are on display.

His faith is evidenced in another of his masterpieces which sits on the table – an intricate chapel featuring a lectern with an open Bible. Knepper’s craftsmanship extends beyond his home and into the heart of the local faith community. Over the years, he has used his talent to create kneeling rails for the altars of three area churches.

The first kneeler was crafted for the Episcopal Church of the Resurrection in Rainbow City, designed specifically to complement an altar the church had received.

This careful attention to detail highlights Knepper’s ability to harmonize his work with existing elements, ensuring each piece feels at home in its setting. Later, he constructed a pair of kneelers for Pell City First Methodist, further demonstrating his commitment to supporting his community through his artistry.

Most recently, Knepper designed a folding, movable kneeler for New Life Church, which gathers at the Municipal Complex in Pell City while a new church is being built. This innovative design reflects his adaptability and practical approach, ensuring the kneeler could be easily moved and stored as needed. Form, function and beauty are hallmarks of Knepper’s work.

A quiet, serious man, Knepper is uncomfortable with attention. He shrugs off accolades, dismissing his own talent. “I’m always using other people’s design, not mine,” he says. “I just put my own spin on someone else’s design.” It gives him something to do, he says, adding that it keeps him from watching TV.

Knepper’s keen eye and ability to see what rough wood can become is what has defined him as an artist and wood carver. Hearing how a discarded root was crafted into a beautiful bowl certainly makes one pause for thought. Each gnarled root or discarded branch may still have a story to tell.

With patience, perseverance and careful listening, the wood carver reveals the beauty within.