One of St. Clair’s oldest churches is still home to many

Story by Joe Whitten

Submitted photos

On Aug. 16, 2020, Macedonia Baptist Church, No. 2, Ragland, celebrated 180 years of faithful spiritual service in St. Clair County. The anniversary celebration occurred on a modest scale because of the current COVID-19 pandemic. The congregation went for regular worship and afterward enjoyed a lunch in the fellowship hall.

The county is home to several churches organized in the early years of both St. Clair County and Alabama.Some churches have surviving records documenting the church’s beginnings, while others have scant information. Over the years, many original minute books met destruction through a house fire where the minutes were stored.

Researchers come face to face with this in researching Macedonia Baptist, No. 2. The official organization date of 1840 is recorded in St. Clair County Baptist Associational meetings, but the year that families began to meet to worship together in the area of Macedonia Mountain lies in the long shadows of two centuries. Furthermore, undocumented published accounts deepen the shadows of the past rather than giving light to them.

In the Daughters of the American Revolution book, Some Early Alabama Churches (Established before 1870) Commemorating the Bicentennial of the United States of America, published in 1973, authors wrote this about Macedonia Baptist: “This church is said to be the oldest church in St. Clair County, and it is thought that it was organized in 1812. It is located in the mountains near Ragland. Records go back to 1840.” However, the authors, Mable Ponder Wilson, Dorothy Youngblood Woodyerd and Rosa Lee Busby, give no documentation for stating this. This is a great frustration to the church and any historian, for someone gave them that information. One can hope that in some old trunk or chest, a forgotten diary or family Bible will come to light to prove the 1812 date.

The Minutes of the St. Clair County Baptist Association for 1932, 1936 and 1942 record 1840 as the official organizational date. The fact is that, as settlers formed communities, families met in homes to worship together. At some point, a circuit-riding minister would come to preach once a month. A desire for a church name and building would burn in the hearts of the group who would petition ministers in the county to help them organize a church. Probably believers worshipped together long before organizing and naming the church Macedonia. The Grizzell and Johnson families are known early members of the church.

The person who gave the 1812 date to DAR also gave a description of the first Macedonia church building. The log structure had no widows. “On the interior of the structure was cube of rocks about three feet long, three feet high, and three feet wide, with a rock shaft going out the side of the building. This was for light when it was necessary to meet a night. Pine knots were burned, giving light, and the smoke went out the shaft. A lean-to that joined onto the building accommodated the slaves.” According to oral history, the first church sat where today stands the pavilion protecting the long “dinner on the ground” tables.

Lela Alverson Grizzell told great-granddaughter Sheila McKinney that a storm destroyed the log structure, but she didn’t give a date for the storm. In a St. Clair News-Aegis article of Oct. 15, 1992, Elise Argo wrote, “The log building was replaced in the early 1900s.” The article indicates Ms. Argo got that date from Brother Archie Maddox, pastor at that time. An up-to-date, wood-frame church replaced the log building, which served the congregation until the present brick structure replaced it in 1948.

In 1956, the church started a building fund to add classrooms. This came to fulfillment in 1965 when the men of the church added two restrooms, a pastor’s study and eight classrooms. In 1985, the men added the fellowship hall with kitchen and dining areas.

The lovely painting gracing the baptistry was done in 1998 by Ken Maddox in loving memory of his mother, Mary Maddox, wife of Brother Archie Maddox.

The original log building served as both church and school according to local family accounts. Shelia McKinney recounted what her great-grandmother, Lela Alverson Grizzell, told of attending the log school.

“The Alverson family settled these hills and valleys, and Lela’s brothers and sisters attended school here,” Shelia recalled. “Lela and her older brothers and sisters walked to school from Macedonia Mountain where they lived. A pond ran over the road, and she told of ice skating on the pond.

“The school had a potbelly stove, and when it rained, they took off their boots and lined them around the stove to dry. They’d wrap their feet in their coats until their feet got warm. Lela said the log church-school blew away in a storm.”

Surviving church minutes of Aug. 20, 1922, show Macedonia as a member of the Coosa Valley Baptist Association, and Rev. Joe Mitchell, pastor, appointing Russell Arnold, Calvin Wood, Henry Johnson, William G. Wilder and J. H. Trammell as messengers to the 1922 meeting. Baptist churches’ messengers represent local congregations and have voting privileges in associational business meetings.

The St. Clair County Baptist Association minutes of the 1929 annual meeting at Broken Arrow Baptist Church, Sept. 14-15, records that “Macedonia No. 2 was received, and the Moderator gave the messengers the right hand of fellowship.” The messengers were M.C. Sagers, H. Johnson, J.S. Bunt and Rosa Jane Bice. Brother Clifford Streety of Pell City was Macedonia’s pastor in 1929.

Macedonia, Ragland, was designated No. 2, and Macedonia, Margaret, No. 1, because the Margaret church had been a member of the association since 1915.

Shelia McKinney, church clerk, has collected church memorabilia and history, some of which is tattered fragments of minutes from the 19th and early 20th centuries. As with many old records on paper, deterioration has taken its toll, but those tattered remains are treasures.

Fragments of old minutes record the Church Covenant and Order of Decorum. As with most early Baptist churches, Macedonia practiced church discipline. The purpose was to help members and restore them to fellowship. Common infractions found in most old church minutes show that drinking, swearing and dancing were causes of “being brought before the church” for discipline and restoration.

The cemetery adjacent to the church is one of the older ones in St. Clair County, and as with all old graveyards, some of the oldest graves are marked by large rocks or crosses. The oldest known grave is that of John Chambliss, May 23, 1826 – Jan. 23, 1881. The oldest person buried there is Chesley Phillips, 117 years old, Aug 7, 1810 – Oct. 25, 1927. According to 1890 church minutes, Macedonia began observing Memorial Day at the cemetery “… on Saturday before the 3rd Sunday in May.” This continues today.

Macedonia’s records show that the Singing Convention often met at the church. Open doors and windows of the church allowed those outside to enjoy the singing going on inside. Newspapers usually announced these events, as shown in this Aug. 12, 1954, St. Clair News-Aegis invitation.

“All-Day Singing, Food Galore, To Be At Macedonia Aug. 15. The Annual all-day singing with dinner on the grounds at noon will be held at Macedonia Baptist Church No. 2 Sunday, August 15. Special singers for the annual event will be Mack Wright and the Victory Quartet, in addition to several others. You are cordially invited to this great day of fellowship,” it reads.

Vacation Bible School week has been another annual event for the church. During the week, children are taught Bible stories and work on crafts or art that correspond with the theme of the week. Several years ago, one of the teachers started the Bible School Quilt, with good results, as shown in the photographs.

Rev. Edwin Talley, pastor of Ragland First Baptist and a former member of Macedonia, said, “I was a member of Macedonia in the early 1980s. It was there that I accepted my calling into the ministry, and there I preached my first sermon. I remained an active member there until I was called to pastor Oak Grove No. 2 in 1986. Macedonia ordained me at the request of Oak Grove. I will always consider Macedonia my home.”

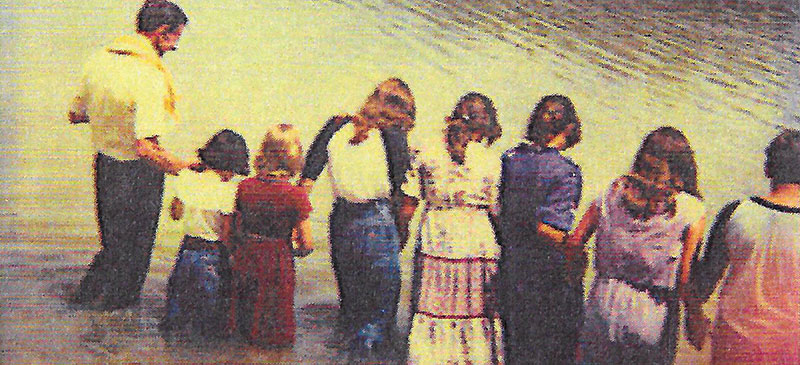

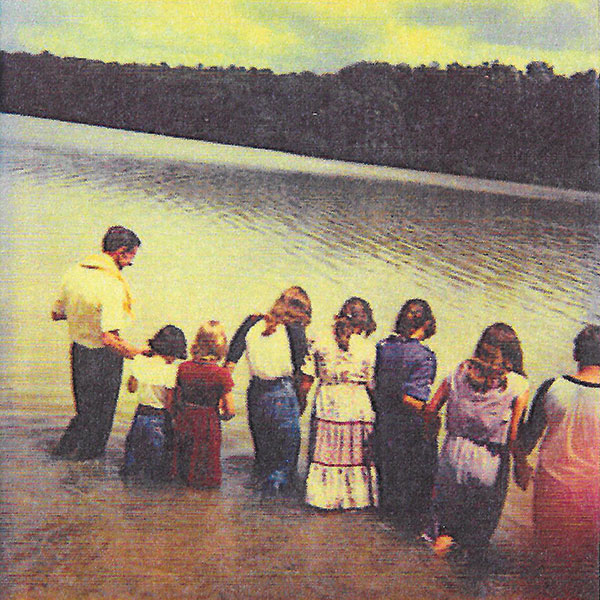

McKinney echoes Talley’s sentiments. When asked for a comment and memory, she replied, “All I can say is, ‘It’s home.’ This was the first church I ever attended. I accepted Jesus in the alter to the right of the pulpit, and I was baptized here. My daughters were saved and baptized here.

“My great-great-grandfather helped organize this church and pastored it. My great-grandparents met and married here. My aunt, Louise Grizzell Sterling, was the song leader for many years, my uncle was a deacon, and my granny taught Sunday school. Following in her footsteps, I also teach Sunday school. Seven generations of my family have attended this church and worked for God here.

“This church – not just the building – the people are my family, and I wouldn’t want to be in any other church – unless God told me to go. I pray that as long as God tarries Jesus’ coming again that my family and I will be here serving God and community to the best of our ability.

“My favorite childhood memory of Macedonia Baptist is learning to recite all 66 books of the Bible in order as they are in the Bible. I was 12 years old, and my granny, Marcene Grizzell, was my Sunday school teacher. Our class had to recite the 66 books in front of the church on a Sunday morning. When we accomplished this, the church gave us our own Bible. I still have mine. My most cherished memory now is that I saw my grandbaby, Katelyn Serenity Byers, dedicated in this church. She is the seventh generation Grizzell descendant attending here.

“I will be buried in the graveyard beside the church with my beloved family members that have gone on before me.”

Brother Bryan Robinson has pastored Macedonia Baptist since 2016. He said, “Macedonia, Ragland, is truly a church that God has ordained to be the church today where we see people saved and baptized even during a COVID-19. This church has seen many wars, the Great Depression and many United States presidents. Over the years, Macedonia’s members have endured many trials and have been victorious through it all. It makes me humble, thankful and truly blessed that God would allow me to help His church go a little further till He comes again. Macedonia members are the salt of the earth. They are a loving, caring and praying people who still use the altar every time the church doors open. I thank God for this church, my church. My wife Sandy and I call it home.”

Each of these referred to Macedonia as Home. What they express connects perfectly with modern Christian author Philip Yancey’s words, “I go to church as an expression of my need for God and for God’s family.” Such is Macedonia Baptist Church, Ragland, a family of believers who feel at Home in church.