A good-hearted town

Story and photos by Jerry C. Smith

Submitted Photos

Tucked unobtrusively between Shoal Creek Mountain and the Coosa River, the St. Clair County town of Ragland does little to pique the attention of passers-through. It’s like the town is taking a well-earned furlough from the generic commerce and sprawl that makes other cities seem so impersonal.

Save for a small dollar store, there’s not a single franchised big-box in sight; no Walmart, Winn Dixie, not even a chain restaurant. Many local folks see this as an asset and willingly drive to nearby cities for their major purchases.

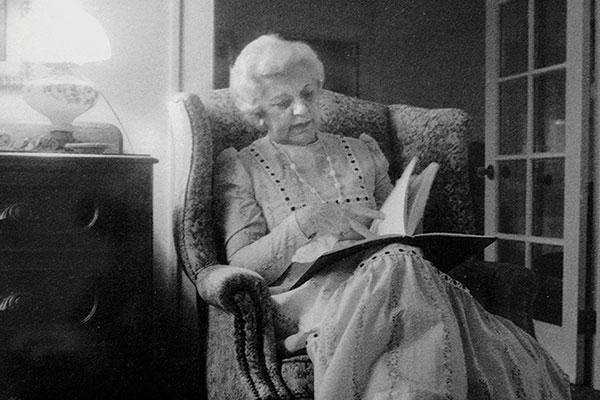

Lifelong resident Joan (Davis) Ford says, “I have a loving heart for Ragland. It still has a lot of country to offer. How great it is to come home and enjoy the peace and satisfaction of owning a home and property here.”

She really understands the concept of coming home, having visited 40 American states and 20 other countries, including Russia.

Wendy Dickinson says of Ragland’s small-town motif, “We have one caution light, one one-way street, one alley, one school, and one red light.”

Mrs. Ford emphasizes that the city is actively seeking new industry, but of a nature that will not seriously alter the community’s idyllic lifestyle. As a former mayor, she’s always been active in education and civic affairs and participated in the formation of the St. Clair Economic Development Council.

The football field at Ragland’s Municipal Complex is named after her, to honor decades of service to the community. She sees the field as an example of how Ragland citizens and businesses have always pulled together to get things done.

Although she was the driving force behind its construction, she quickly shifts credit to others; “The community built that field. We had high school football players and volunteers from the cement plant who came after-hours to work there, and all I had to do was call National Cement and let them know what we needed, like a load of cement or rock or whatever, and they were right there with it. They also gave us a check for $10,000 to help cover expenses.”

Some of the hard labor was done by prisoners from St. Clair Correctional Facility, who were always eager to work because the town ladies fed them so well at lunchtime. “The guards said they would almost have fights at the bus every morning to see who got to go to Ragland,” she said.

In gratitude, the prisoners built a memorial barbecue pit next to the field, keeping it hidden under a tarp as a surprise for her when the project was done.

At age 81, she remembers a much more vibrant Ragland. “This place was hopping in the 40s and 50s. The streets were lined with businesses of all kinds, and people crowded the streets and sidewalks on weekends.” She also recalls when all the roads were unpaved and full of horses, wagons and carriages.

Mrs. Ford reminisces about town life during her childhood: “There were all kinds of businesses downtown, with several restaurants, one of which even allowed dancing. There was a movie theater called the BoJa (pronounced Bo Jay).

When the Walt Disney movie Bambi came to town in the late 40s, school let out and the kids got to walk across town to see it. Mr. Haynes sold bagged peanuts and popcorn balls in front of the theater.”

Ragland is home to two major companies that have been in operation more than a hundred years each — Ragland Brick Company and National Cement Company. Besides these plants, Ragland was once heavily committed to the coal and lumber industries, providing products and minerals of high quality that were distributed worldwide.

Truckloads of lumber regularly left the Dickinsons’ sawmill for Birmingham and beyond, while Ragland’s superb low-sulfur coal was much in demand for blacksmithing and the iron industry, even during the Civil War.

When Mrs. Ford’s father worked at the cement plant, the Davises lived in a community of some 15 company houses called Frog Town, so-named for the abundance of croaking frogs at night. Company officials lived in another neighborhood of swankier homes, called Society Knob.

Mrs. Ford remembers catching fishing worms along the banks of a little branch, and her horror when she caught some baby water snakes by mistake. She’s presently working with Ragland officials to obtain a historical marker for the Frog Town area.

She also tells of Elmer “Paw Pa” Davis driving a wagon that hauled mail sacks from the train depot to the post office, a simple but important daily event for many small towns.

A big black man called Patches sat beside Paw Pa on an old wood bench seat. Sometimes she joined them there, but would ride with her legs hanging off the tailgate if she was with friends. The wagon was drawn by a retired army mule named Maude, who had the letters US branded onto its side.

Mrs. Ford sees Ragland as a place with real heart, where people have always pulled together during times of need, a sentiment echoed by others. “If there was anything that happened, deaths or disaster or whatever, it didn’t matter who you were or what you believed in, you got help,” she said.

She’s especially proud of her church, Hardin’s Chapel Bible Church (non-denominational), whose facilities saw heavy usage during the months following the tornado that wracked Shoal Creek Valley.

“The whole community responded with volunteer work, food, supplies and clothing. Seven ladies and I fed hundreds of people from our kitchen. We came in at 5:30 in the morning, and rotated 12-hour shifts. I told them to be ready for a long haul, because this thing would not be over in a few days, more like several months. And bless their hearts, they stuck by us the whole time.”

She also recalls when the tornado of 1974 came through, tearing things up so badly you could not get to Ragland on any road, and how people had pulled together then, like they always do.

It seems Ragland has been blessed over the years with folks whose love of community and their fellow man inspired them to empathize and share what they had with their neighbors. Such a man was Pop Dickinson, for whom Alabama Highway 144 was re-named shortly before his death in 1982.

POP DICKINSON

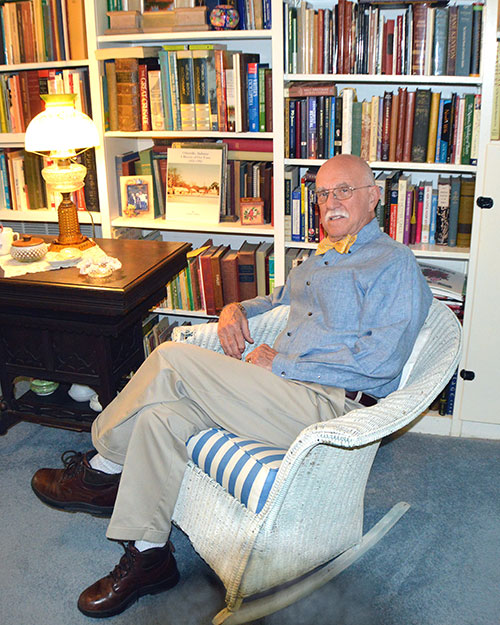

Leon Ullman Dickinson, always known as Pop, came to Ragland from Lincoln in the late 1930s as the Depression was winding down and quickly became legendary for the way he treated (and trusted) people.

He freely gave credit to customers at his sawmill and lumber operation in Ragland, which he and his brother Hal had begun while still in Lincoln. Pop was also known for financing mortgages for those whom the banks had refused. Pop ran these business interests with help from son Lowell Leon “Buck” Dickinson and his grandson, Robert Leon “Bob” Dickinson (all three men had Leon in their names).

According to granddaughter Wendy Dickinson, when Bob wanted to foreclose on a woman, recently widowed, who could no longer make payments, Pop told Bob that if he needed that house more than the widow needed it, he would buy Bob’s part of the company and absorb all the loss himself. Bob relented and simply gave up his share.

According to granddaughter Wendy Dickinson, when Bob wanted to foreclose on a woman, recently widowed, who could no longer make payments, Pop told Bob that if he needed that house more than the widow needed it, he would buy Bob’s part of the company and absorb all the loss himself. Bob relented and simply gave up his share.

Meanwhile, Buck went on to other ventures, which included starting the first telephone exchange in Ragland with nine old magneto crank phones, like the ones seen on vintage TV shows where you crank a handle and ask an operator to connect you.

This company later expanded into the present-day Ragland Telephone Company, operated by Bob after Buck’s death in 1959, thence by Bob’s widow, Peggy Alexander Dickinson, after his death in 1982. It has always been a privately held utility, with no connections to the big comms like AT&T.

The Dickinsons were well-involved in local politics. Buck and Bob both served as mayors. Bob was a Democratic Party delegate in the 1960s and also started Ragland’s first TV cable company.

Bob’s wife, Judith (Mitchell), formerly of Leeds, was Ragland’s first female mayor and also served two terms on the Board of Education. She was highly praised in her 2007 obituary by current BOE Superintendent Jenny Seals. Judith’s brother-in-law, Ed Goodson, was a mayor of Leeds.

Birmingham News writer Thomas Spencer describes Judith, “Judy … loved to wear outlandish hats to church; a red felt one with netting on the front and a big feather sticking out of a bow in back, and a pink one with sequins and a ponytail holder.

“At Christmas she wore one festooned with colored lights. She was flamboyant and fearless about what other people thought. She just wanted them to smile. … At her request, they played the bombastic, cannon-firing 1812 Overture at her memorial service.”

Wendy tells of Pop’s personality, “He was a very good man, who never touched liquor or missed church, although one time he fell asleep in church because of the time change, and everybody thought he was dead.”

Wendy says Pop loved to fox hunt, but never killed a fox because he just wanted to hear the dogs run. “He beat the heck out of one of his dogs once for killing a fox, but later found out the poor dog hadn’t done it, and he felt bad for weeks afterward, cuddling that dog and telling him how sorry he was for the beating.”

She adds that Pop made his own dog food from scratch and openly carried a gun while patrolling their neighborhood at night.

Several vintage Raglanders spoke of Pop’s total lack of driving skill, often weaving all over the road at breakneck speed, running traffic signs and never giving turn signals.

Wendy says Pop once bought a pickup truck with an automatic transmission, hoping it would allow him to concentrate less on shifting and more on driving, but quickly tore the transmission up trying to shift gears anyway.

A Mr. Barnhill, with whom your writer chatted at Ragland Civic Center, tells that he once rode in a carload of kids along with Pop. They were on their way to a ball game, and Pop made the owner of the car pull over and let him drive because he felt they weren’t going fast enough. Barnhill still recalls how quickly that ride turned fearsome once Pop took the wheel.

Pop passed away in 1982, just days from his grandson Bob’s demise, and is buried in Birmingham’s Elmwood Cemetery.

The Pop Dickinson Highway sign is long- gone, but most anyone in town will affirm the real name of Alabama 144.

WATT T. BROWN, GODFATHER OF RAGLAND

Some refer to Watt Brown as the Sumter Cogswell of Ragland. He was there in the town’s earlier years and was largely responsible for its coal industry as well as active interests in virtually every other major endeavor in the area.

In her book, From Trout Creek To Ragland, historian Rubye Hall Edge Sisson says of Brown, “His influence would color Ragland more than any other individual.”

It’s said that at one time he owned so much land that one could walk all the way from Ragland to Odenville and never set foot off his property. Indeed, he contributed greatly to the development of Odenville and Coal City as well.

Born at the closing of the Civil War in the Talladega County settlement of Kymulga near Childersburg, Watt grew up in Ohatchee. At age 18, he partnered with the Green mercantile firm, then joined his brother James as a stockholder in Ragland Coal Company, soon to be joined by another brother, Adolphus.

Always a mover, by 1893 Watt had become president of the company, and the brothers started buying up mineral-rich lands all over St. Clair County, reaching as far as Coal City and Odenville.

He succeeded in getting a major portion of Coal City incorporated as Wattsville. The town’s name was also given to a major seam of fine coal that underlies a large part of St. Clair.

Ragland had originally been known as Trout Creek, after the stream that still flows through the heart of town and once caused a major flood with great damage. In 1899, Brown and others petitioned for Ragland’s incorporation, naming it after the family who owned Ragland Coal Company. Watt presumably served as its first mayor.

A few years later, he married Ashville Judge Inzer’s daughter, Lila, gaining both connections and a stepson in the process. He also formed Brown Construction Company to take advantage of the economic boom he was helping to create.

Over the next two decades, Watt served in the State House of Representatives, as chairman of the St. Clair County Executive Committee, as alderman for Ragland, and as a state senator. With others, he formed the Ragland Water Power Company, hoping to build a hydroelectric plant at Lock Four, but was pre-empted by another project proposed by Alabama Power Company.

Sisson lists more of his accomplishments: “The Progress, a newspaper published in Pell City, endorsed Watt Brown … in his first run for Senate (saying that) during Watt’s term in the State House he had helped the Pell City cotton mill, brought the brick plant to Ragland, and had been a moving force in securing the cement plant.

“Other newspapers … proclaimed him a captain of industry who had made millions. He was president of Odenville Bank, a director of Anniston National Bank and Alabama Life Insurance Company, and trustee of the Jacksonville State Normal School.”

Sisson also credits Watt Brown with building a St. Clair High School in Odenville in 1908 that served students from the whole county. He spearheaded a drive to get a high school for Ragland, offering huge tracts of his own land to sweeten the deal.

But not every project started by Brown came to fruition. He’d wanted an industrial school in Ragland, but the powers chose to build it in Gadsden instead. Likewise, his bid for a tuberculosis sanitarium was rejected, as well as a cotton mill using local resources and labor to make shipping bags for the cement plant.

Brown never tired of promoting Ragland. Sisson continues: “When the Alabama State Land Company proposed to publish information on … the natural resources, climate etc. of Alabama, Watt described Ragland in glowing terms. … Alabama State Land encouraged him to print his own brochure. This brochure was sent all over the country.”

Jenna Whitehead, in a 1974 story in St. Clair News Aegis, quotes (another writer) as saying, “During the Depression, Brown wrote down a 10-point plan that would pull the country out of the Depression,” remarking that it was almost identical to the plan later tendered by President Franklin Roosevelt.

Yet, for all his forward-looking ideas and tireless promotion of the towns he loved, not everyone approved of Watt T. Brown. In a recent interview, your writer encountered a lady who claims that her mother would never use the name Wattsville, always clinging to its previous name, Coal City, even to the point of getting a post office box in another town so her mail would never bear his name. It’s also said that a man had rented some retail space in Odenville’s Cahaba Hotel, which Brown built and owned outright. While the tenant was moving in, Brown approached him and asked how he intended for customers to enter his business.

The man told him they would enter the front door — how else? Brown then informed him that he owned the sidewalk and the tenant would have to pay a usage fee.

In 1930, Brown ran for governor, with a brilliantly conceived platform that was way ahead of the times. He put everything he had on the line, and lost.

Apparently, he had overestimated the admiration of his constituency. Watt T. Brown quickly sank into destitution and obscurity, dying in poverty some 10 years later. The man who had practically fathered at least three towns and made a huge fortune for his family was so poor he was buried in a borrowed spot until his family finally moved him to their own plot at the Methodist Cemetery.

Today, only a few eastern St. Clair old-timers (and a historian or two) even recall his name.

MEET RAGLAND

From US 231 at Coal City, it’s only a few pleasant miles’ drive to Ragland. Along the way, you’re treated to numerous pastoral scenes, some with long, white wooden fences.

There are several historic churches, among them Harkey’s Chapel Methodist and the aforementioned Hardin’s Chapel. Watch for interesting road names, such as No Business Creek, Memory Lane, Homebrew Knob and Center Star Road as you drive.

Near Ragland, a wooded bend in the road suddenly opens to expose one of the town’s main industries, National Cement Company, alongside the remnants of an old football stadium, barely visible through the overgrowth.

Alabama 144, aka Pop Dickinson Highway, becomes Church Street, Ragland’s main crossroad, thence to Main Street. The historic, picturesque Champion Drug building, originally the Lee Hotel, dominates this intersection. Now awaiting repurposing, this fine old structure played various roles in the town’s early history.

Trout Creek crosses Church Street next to the railroad tracks, the Methodist Church and the old depot. Ragland Brick is just west of the church.

Before leaving town to the east, consider taking a few side roads to see dwellings more than a hundred years old, many of them company houses.

As you exit the downtown area, there’s a fine library and the town’s main supermarket, the Food Barn, reminiscent of an earlier, less gaudy era. Shopping there is almost like stepping into a time machine.

A mile or two farther eastward on Alabama 144 lies Neely Henry Dam, thence onward to Ohatchee at Alabama 77. Just a few blocks northward on Alabama 77 is the Spring Street turnoff for Janney Furnace and Museum, a great site to visit at GPS coordinates 33 47.712N 86 1.164W

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

While Ragland is typical of many aging Alabama towns with a more vibrant past, it’s currently primed for new ideas and energy. As Mrs. Ford said in our opening paragraphs, it would be a great place to call home and start a new business that doesn’t depend on heavy road-frontage traffic.

The municipal complex, tucked quietly away on landscaped grounds just west of downtown, is totally adequate for official, recreational, senior citizen, and athletic functions.

Among its amenities are a splash pad, a walking track designed by Judith Dickinson and Rufus Bunt, the Dustin Lane Ford baseball and softball complex, a very active Senior Citizen Center, and a playground.

Everything one really needs for a simple, front-porch life is right there. Best of all, a century-old tradition of togetherness and mutual aid still thrives in Ragland.

In a word, it’s home.

A needlework plaque on the kitchen wall says it all: Hard work is the yeast that raises the dough. John, his wife Sara, and Gayle Hammonds were prime movers for the entire project and continue their leadership roles today, but other folks and factions have generously lent their support.

A needlework plaque on the kitchen wall says it all: Hard work is the yeast that raises the dough. John, his wife Sara, and Gayle Hammonds were prime movers for the entire project and continue their leadership roles today, but other folks and factions have generously lent their support. In addition, its main purpose is to serve as a rentable venue for small community group functions, including club meetings, showers, parties and other gatherings. Although actual occupancy is limited by fire law to 16, Gayle says there is ample level lawn space for tents, booths, outdoor festivities and overflow crowds.

In addition, its main purpose is to serve as a rentable venue for small community group functions, including club meetings, showers, parties and other gatherings. Although actual occupancy is limited by fire law to 16, Gayle says there is ample level lawn space for tents, booths, outdoor festivities and overflow crowds.

In April, Progress reported that folks in Ashville and Springville claimed “inside information,” and were of the opinion Pell City had “no chance” of being selected. But rather than losing heart, Pell City published that they had “the best chance” based upon the facts submitted in connection with the state’s proposal for location.

In April, Progress reported that folks in Ashville and Springville claimed “inside information,” and were of the opinion Pell City had “no chance” of being selected. But rather than losing heart, Pell City published that they had “the best chance” based upon the facts submitted in connection with the state’s proposal for location.

On the other hand, floors are littered with a veritable snowfall of white flakes of ceiling paint and decades’ worth of other detritus. In some secluded spots, there is bat guano. Leftovers from several former users are piled here and there. Reconstruction materials are stacked haphazardly among the chaos.

On the other hand, floors are littered with a veritable snowfall of white flakes of ceiling paint and decades’ worth of other detritus. In some secluded spots, there is bat guano. Leftovers from several former users are piled here and there. Reconstruction materials are stacked haphazardly among the chaos.

Story and photos by Jerry Smith

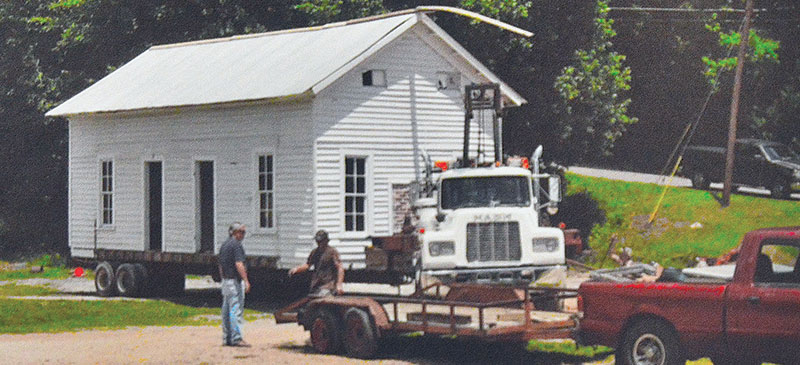

Story and photos by Jerry Smith A lover of all things historic, she could not bear to see this fine old structure demolished. Reluctant to put themselves at odds with the indomitable Mrs. Crow, the County Commission agreed that she could have the old building provided she moved it somewhere else, and soon.

A lover of all things historic, she could not bear to see this fine old structure demolished. Reluctant to put themselves at odds with the indomitable Mrs. Crow, the County Commission agreed that she could have the old building provided she moved it somewhere else, and soon.

A beautiful young lady in Miss Mabe’s Bible class at Bob Jones raised her hand to answer a question. Joe, who was sitting behind her and had wanted to answer first, grabbed her arm to try to lower her hand. This incensed her, and she reminded him in no uncertain terms that this school had a rule against opposite sexes physically touching one another.

A beautiful young lady in Miss Mabe’s Bible class at Bob Jones raised her hand to answer a question. Joe, who was sitting behind her and had wanted to answer first, grabbed her arm to try to lower her hand. This incensed her, and she reminded him in no uncertain terms that this school had a rule against opposite sexes physically touching one another. Gail taught school at Ragland for a while, then transferred to Odenville, where she taught in the elementary grades. Her classroom was next to the library where Joe worked at the time.

Gail taught school at Ragland for a while, then transferred to Odenville, where she taught in the elementary grades. Her classroom was next to the library where Joe worked at the time. Joe, the poet

Joe, the poet