Efforts begin to save one of St. Clair’s most storied structures

Story by Robert Debter

Submitted Photos

The story of the Looney Family, among the first settlers in St. Clair County and one of the oldest in state of Alabama, begins over 200 years ago on the high, east bank of Tensaw Lake, which had been from an old channel of the Alabama River at a place named Fort Mims.

The fort began as the fortified plantation of early settler Samuel Mims and consisted of 17 buildings, a blockhouse and a log palisade.

Following the victory of the Red Stick Creeks at the Battle of Burnt Corn Creek on July 27, 1813, over 500 settlers from the surrounding area sought refuge at the fortified home. Maj. Daniel Beasley and 70 volunteers of the Mississippi Territorial Militia were sent to garrison the fort, while another 100 volunteers were sent to other nearby posts and forts.

At noon, on Aug. 30, Red Stick warriors, led by William Weatherford, or “Red Eagle,” assaulted the haven by rushing though the fort’s open gate and firing through the gun ports. Maj. Beasley and his militiamen fell during the first part of the enemy’s attack.

It fell to Capt. Dixon Bailey, a Creek, and his force of Americans and Creeks who repelled the hostiles for four hours. The battle ended when the fort’s buildings were set ablaze. The casualties numbered from 300 to over 400, mostly women and children.

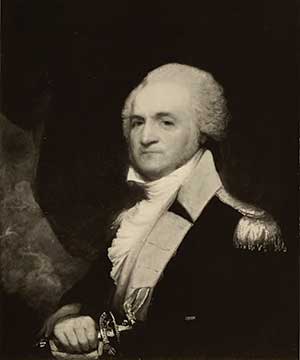

Gov. Willie Blount (pronounced “Wylie”) of Tennessee was quick to react and the state legislature authorized him to summon 5,000 troops to defend the Mississippi Territory. Major General of the Tennessee Militia, Andrew Jackson, who was recovering from a near fatal brawl in Nashville, was given command of the volunteer forces.

On Oct. 7, with his arm in a sling, Jackson and his second in command, Gen. John Coffee, departed Camp Blount in Fayetteville. They made their way south and later erected Fort Strother along the Coosa River in present day Ragland.

The Creek War came to a close following the Battle of Horseshoe Bend on March 27, 1814, and many familiar names of places in Alabama came about as result of this often-forgotten war, such as: Moulton and Somerville and the counties of Blount, Coffee, Jackson, Lauderdale, Montgomery and Wilcox.

St. Clair beginnings

Among the brave Tennessee volunteers were John Looney and his son Henry, of Maury County. During the war, they had come through this land, helped construct Fort Strother, and fell in love with the beautiful country that surrounded them during the campaign.

In the aftermath, father and son returned to Maury County and in 1816, John began selling his land. In late 1817, he, his wife Rebecca, and their children left Maury County, bound for the land described by Julia Tutwiler, as “Goodlier than the land that Moses climbed lone Nebo’s mount to see.”

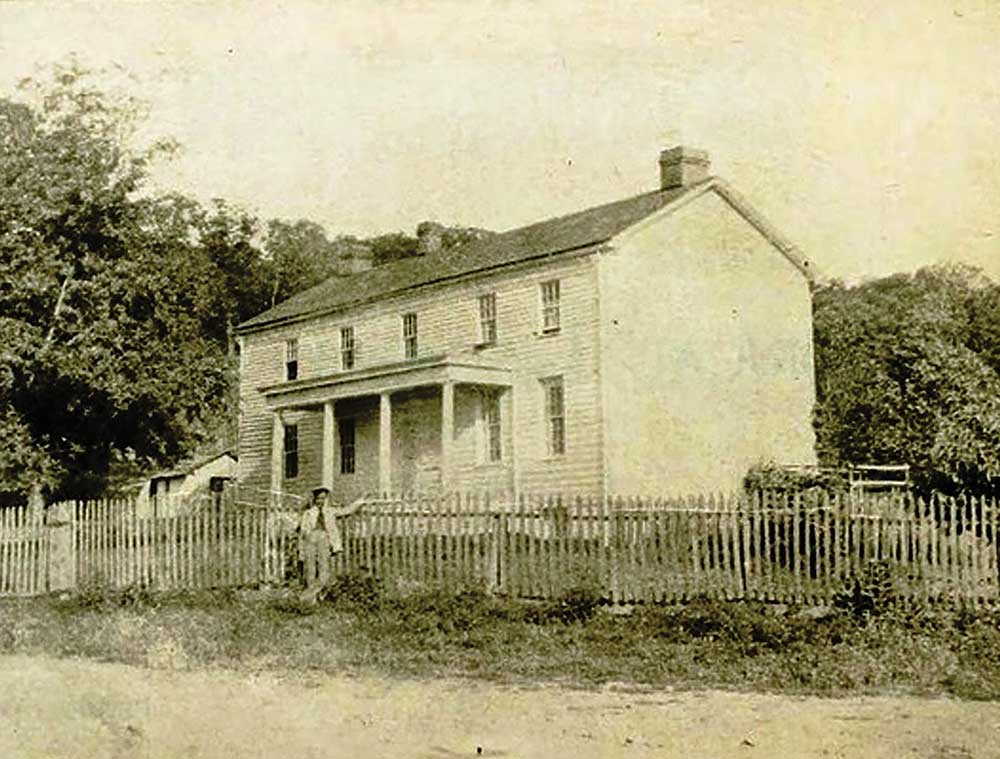

Trusting in the Lord with their hearts and leaning not on their own understandings, the John Looney Family settled in Beaver Valley in 1818, and the site they chose was near a sparkling spring, not far from Little Beaver Creek. They soon began work on their house and were finished by the winter.

The new spring brought with it swarms of mosquitoes, illness from fever and chills and a flooded home. A new home place was found nearby, and the house was moved to higher ground where it has stood ever since.

John Looney became a prominent leader in the young St. Clair County, serving as a justice of the peace and foreman of the first jury. After his death in 1827, Henry became head of the family and married Jane Ash, the daughter of Ashville’s namesake John Ash, on Oct. 25, 1838. Henry departed this life in 1876 at the age of 78 and was interred at Liberty Cemetery in Odenville. Jane moved to Texas around 1888 to live with her son George and died there in 1900, aged 85. She was laid to rest in City Greenwood Cemetery in Weatherford, Texas.

Henry’s siblings were Jack (married to Lucinda Cooper), Asa (Joyce Cooper), Absolom (Nancy Chenault), Sophia (John Cooper), Elizabeth (Wylie Yarbrough), Isaac (Elizabeth Hammond), Wylie (Laurinda Little) and Melinda (Hugh Cooper).

The Looney House, with all its history and dovetailed, heart of pine logs, was sold in the late 1800s by D.W. Looney to John and Eliza Lonnergan. It remained in the Lonnergan Family until it came into the possession of Col. and Mrs. Joseph R. Creitz.

The house, once the perfect picture of pioneer architecture and Southern resolve, was now without a roof, missing many of its window panes and overgrown with honeysuckle. In March 1972, the couple offered the house to the county or any historical organization that would vow to restore the property.

Historical Society steps in to save structure

On April 8, 19 people attended the founding meeting of the St. Clair Historical Society at the Odenville Community Center. On Sept. 15, the house and property were given to the St. Clair Historical Society for $10 and by the end of the society’s first year, its membership measured over 500.

Mrs. Mattie Lou (Teague) Crow valiantly led from the front and organized the restoration of the home. A cedar shake roof was installed, window panes were replaced, and the grounds were cleared, with much appreciation being extended to the Ashville Garden Club and the John Pope Eden Career Technical Center.

The front porch was restored by Jack Bowling of Rainbow City for the cost of around $2,600 and it was said, “It’s as near to the original as we could build it,” as a great deal of research was conducted to determine how the first porch looked.

The rock steps, quarried out of Beaver Mountain and hand hewn, date back to the 1860s and were donated from the old Cox house in Beaver Valley. Wild roses and four o’clocks were planted. For the inside of the house, Miss Nan Young made the rugs and Miss Nellie Patterson made the briar-stitched curtains.

Furnishings and decorations were donated from treasures found in the homes of many St. Clair Countians: Karl Scott donated a pegged rope bed; Ann Riser gave a lovely chest of drawers which opens into a desk; Elizabeth Teague donated a period rocker; and the Rankin Family gave a beautiful wardrobe.

Howard Hill gifted a set of candle molds, which belonged to his grandfather, and his wife, Elizabeth, the great-granddaughter of county pioneers Littleton Yarbrough and Reuben Phillips, donated a reel, for arranging thread, from her great-grandfather Reuben Phillips’ plantation and a butter mold used by her mother, Sallie (Phillips) Hodges.

The first of the St. Clair Historical Society’s Annual Fall Festivals took place over the weekend of Nov. 23 and 24, 1974, and the grand opening of the museum was attended by a crowd of over 2,000. The ribbon cutting was officiated by Dr. James McClendon, the father of Sen. Jim McClendon, and music was provided by the Springville and St. Clair County High School bands.

The Looney House was soon added to National Register of Historic Places and on Feb. 15, 1975, a certificate, signed by Alabama Gov. George C. Wallace, recognizing this achievement was presented to the St. Clair Historical Society.

In 2018, descendants of John and Rebecca Looney came together from all over Alabama, as well as Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas and Utah in a homecoming celebration as part of the St. Clair County Bicentennial.

Until a tragic fire destroyed it on Aug. 6, 2022, it was considered one of the oldest-standing, two-story, dogtrot houses in the state of Alabama.