Perseverance’s payoff: Big Canoe Creek Nature Preserve ready for visitors

Story by Carol Pappas

Photos by Mackenzie Free

It was a word repeated early and often in what would become a decade-long journey to Big Canoe Creek Nature Preserve – “perseverance.”

But on a clear, Spring-like day in February, close to 400 people witnessed just how perseverance paid off.

It was billed as a ribbon cutting. What it became was testament to what can happen when visionaries don’t give up.

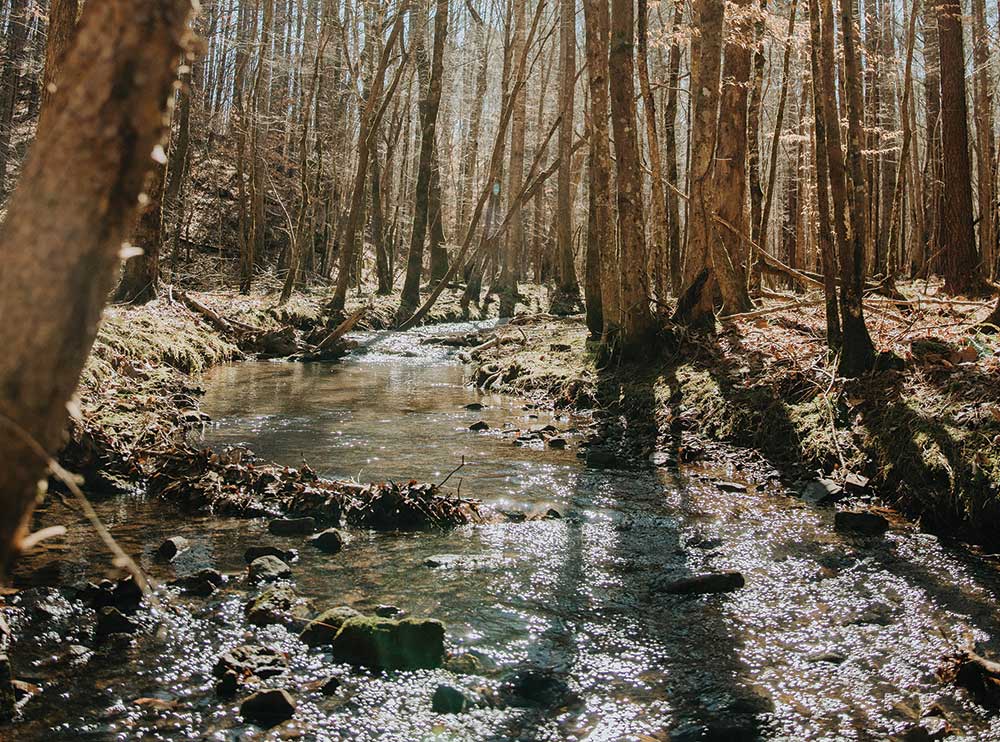

The much anticipated, much heralded Big Canoe Creek Nature Preserve officially opened, marking the end of one journey and the beginning of many more. This 422-acre slice of Alabama nature tucked away alongside a pristine creek in Springville blends miles of trails for hiking, biking, horseback riding, birding and just plain enjoying nature.

Plants, flowers, trees of all descriptions dot the landscape. A crystal-clear creek meanders through the heart of it. Below its surface, rare aquatic species have found a home. Towering trees form the ideal canopy for the trails below.

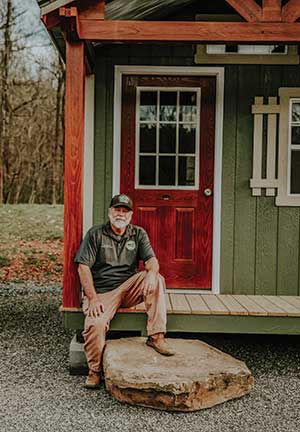

It’s a scene no doubt played and replayed in the vision of people like Doug Morrison, whose passion to preserve, protect and share nature’s gem never ceased. Perseverance.

It’s a scene where one by one, a burgeoning army joined in the advocacy, embracing the vision. The Friends of Big Canoe Creek, Dean Goforth, St. Clair Economic Development Council, Springville City Council, St. Clair County Commission, Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, State Lands Division, Freshwater Land Trust, Forever Wild, Nature Conservancy and Big Canoe Creek Preserve Partners became an unstoppable coalition of noteworthy impact on generations to come. Perseverance.

And it’s a scene where a new journey began once those gates opened, drawing multitudes now and in the future to – as Morrison puts it – “explore and discover” the natural treasures found within its borders. Again, perseverance.

The day following the ribbon cutting, the gates opened officially to the public for its very first day, Feb. 3, and 731 streamed in throughout the day. That’s over 1,000 people in just two days, and the enthusiasm and allure have shown no signs of slowing since.

Springville Mayor Dave Thomas said he had not visited for about two weeks after the opening and decided to check in one morning. The upper parking lot was full, and the traffic kept coming. “It was 10 o’clock in the morning on a Thursday,” he said, the note of surprise evident in his voice.

At the opening, Morrison talked of the Alabama Forever Wild program and the wonder of its impact on the future. “They are taking this property and buying it to set aside for people forever. It will be for this community from now on.”

The abundance of biodiversity is now protected. “We really are blessed here,” Morrison said.

A main focus of the preserve, in addition to its recreational value, will be its education component. No sooner had the ribbon been cut than the first education outreach program was announced – a turkey call expo.

Youths from all over were invited for a day of learning all about turkey calls, making them and enjoying the outdoors. Outdoor classrooms will be a hallmark of the preserve.

Thomas called the preserve “a fantastic opportunity to protect the ecosystem and promote conservation education among students and parents. This will be generational. It will outlive us all.”

Commission Chairman Stan Batemon, who was a game warden in his professional career, knows firsthand from both roles the benefits and potential of the preserve. “This is the ground level of economic development,” he told the crowd. He talked of young people and an emphasis on work ethic through groups like the Cattlemen’s Association and 4-H, which can use the preserve as a resource for “building up and creating a workforce.”

And Morrison centered on a community of people who came together around a common good. When skills and expertise were needed in each area along the journey’s way, he recounted, community stepped up to make it happen. Whether it was securing the land, building a website, painting, paving, addressing environmental needs, carpentry, trail design, providing funding or dozens of other issues, someone always came forward.

“People in this community care,” Morrison said as he reflected on years ago when he and wife, Joannie, moved to Springville, his home on the banks of Big Canoe Creek. “Destiny brought us here, honey,” he told her.

And perseverance brought the preserve to this moment.

Key Players

A project of this magnitude had to have a team. When their number was called over the past decade en route to opening day, these agencies all played a role in acquiring and transforming the Preserve into a winner:

- City of Springville

- St. Clair County Commission

- St. Clair Economic Development Council

- Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, State Lands Division

- Alabama Freshwater Land Trust

- Alabama Forever Wild

- The Friends of Big Canoe Creek

- Coosa Riverkeeper

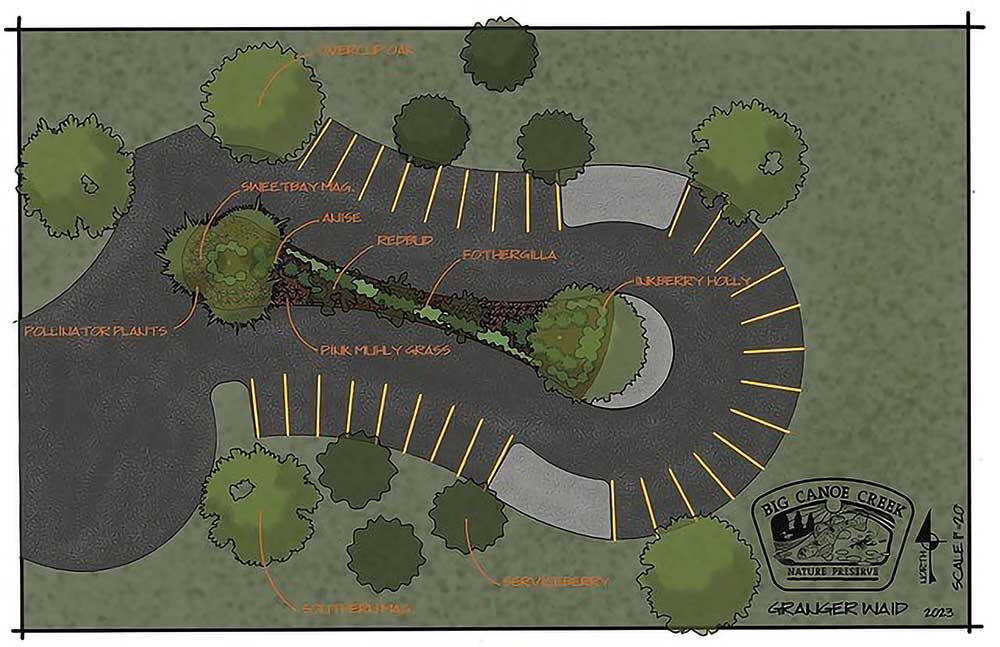

- Norris Paving / Granger Waid

- Schoel Engineering / Joey Breighner

- Alabama Metal Arts

- Tracery Stone

- Sterling Iron Works

Major Contributors

- EBSCO

- Community Foundation of Greater Birmingham

- G.T. LaBorde

- Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alabama