Creator of many; master of all

Story by Carol Pappas

Story by Carol Pappas

Photography by Mike Callahan

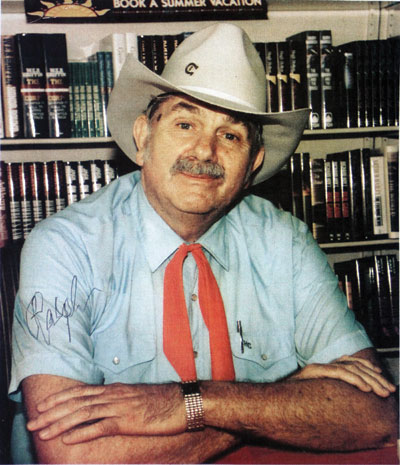

When lightning struck a tree in Bill Golden’s yard, the natural instinct was to grab a chainsaw. But as quickly as that bolt shot through the tree, an idea struck Golden.

So with chainsaw in hand and a makeshift scaffold surrounding the tree, he masterfully turned the 12 feet of its remnants into an Indian carving that now stands watch like a sentry over the shoreline that fronts his Logan Martin Lake property.

Take a look around outside and inside his home, and one can’t help but conclude that just as he carved an impressive sculpture out of nothing more than a tree stump, Golden makes a habit out of turning challenges into opportunities.

“I do a lot of different things,” Golden said. “God has given me the abilities, and I’m not afraid to use them.”

Fear is not a word — or an emotion — Golden knows well. Why else would he try to create a stained glass window without so much as a moment’s lesson? But step up on his front porch and come face to face with a stained glass work of art.

He had been encouraged to take a class, but he told the woman where he bought his equipment that he “read a book.” When he returned for more equipment, she again encouraged him to take a class. “I’m doing OK,” he told her.

In the third week of his project, the notion of a class was dangled in front of him once again. “No, I’m doing fine,” he assured her.

By the end of the fourth week, the window was finished. He took a picture to show her, and she was “flabbergasted. ‘You could enter this in a contest,’” he recalled her telling him. And adding the ultimate compliment, she said, “‘I’ve got a door I’d like you to do for me.’”

“That’s where I messed up,” he chuckled at the memory. “I could have made a little money at it.”

Dollars don’t drive him, though, challenge does. “He is very talented,” his wife, Beth, said. “I have never asked him to do anything he couldn’t do, and it’s always better than I describe it — and always bigger.”

A retired supervisor from Hayes Aircraft and once a senior designer at SMI Steel and a project engineer at Connor Steel, his resume also includes an animated film — not because it was in his job description. It was simply a need at the time, and he accepted the challenge.

Hayes was vying for a NASA contract. “My boss called me from Houston and said he told NASA that I was an animation expert. I told him I knew nothing about animation, that I had seen animations about Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse. He told me to go downtown and buy any books you need. I bought three books.”

Three months later and with an animation film to his credit, Golden said his boss called him into his office and said they won the NASA contract. Another hurdle; another challenge met by Golden.

Inside his Logan Martin Lake home today, you’ll find plenty of evidence of Golden’s handiwork. In the foyer is a framed, pen and ink drawing that looks as though it could be on display in an art gallery. The signature on it? Golden’s, of course.

Inside his Logan Martin Lake home today, you’ll find plenty of evidence of Golden’s handiwork. In the foyer is a framed, pen and ink drawing that looks as though it could be on display in an art gallery. The signature on it? Golden’s, of course.

Nearby hangs a three dimensional music sheet he created with actual piano keys from the family’s century-old piano forming the notes of doxology, “Praise God, from whom all blessings flow.”

Then there is the 300-pound roll top desk he fashioned out of red oak, various paintings and carvings of toys, figures and dolls, the table he built from an oak tree and the room-sized Christmas village display complete with a mountain landscape overlooking it. The snow-capped peaks he painted stretch across two walls of the room, the natural light coming through a window behind it following the natural path of the sun setting. Oh, and it’s not a canvas, it’s an old sail he turned into one.

These and more are all Golden originals, but he takes particular pride in the 7-foot “Chief Coosaloosa,” dressed in leather, holding a hatchet in one hand with the other hand over his heart. The inspiration came from the trunk itself. A growth on it looked like an arm stretching across a chest, Golden said. “I felt obligated to carve that Indian.”

Its history didn’t begin with the lightning strike, though, it was one of three trees he bought 40 years ago from Sears and Roebuck and planted on the property that lies across the road from present day Pine Harbor golf course. When he bought the lakefront property, Pine Harbor was merely a cotton field, he said.

When lightning struck his prized tree, he decided to save at least a piece of it. He told the tree cutting company to leave him a 12-foot stump. Golden built a 12-by-12-foot platform around it about 3 feet off the ground and over the next four weeks, Chief Coosaloosa began to emerge. “I started at the top and came down with an electric chainsaw.” Feathers, leather jacket and pants, moccasins, the hatchet, the chiseled look of his face — all are lifelike. It took Golden a week to stain it, and it now stands as a landmark for anglers and boaters alike who have discovered it.

Another landmark stands — or turns — just a few feet away. It is a waterwheel he built that serves as the end of his heating and cooling system and also produces enough water for doves he raises in a former greenhouse, a pen and a pond. And, “It’s more efficient air conditioning than the unit outside,” he said.

Where does all that ability come from? Perhaps it’s in the genes. “My dad had a reputation for fixing anything,” he said. Or perhaps it’s simply drive. “I’ve still got a lot of things to do before I check out. Everything you see (even the house itself), I did. I’ve still got more to do. I haven’t gotten to the end of that list yet. I enjoy retirement as retirement is supposed to be enjoyed.”

So what’s next? Well, there is that cedar log that could be turned into a football player with a leather helmet. …