EDUCATION & PERFORMING ARTS

‘What If’ played big role for CEPA

Story by Leigh Pritchett

Story by Leigh Pritchett

Photography by Wallace Bromberg

Submitted photos

Once there was a city that needed an auditorium.

Once there was a school that needed a better gymnasium.

The city and the school system decided to join together to do what neither could do alone.

When even the combined efforts were not quite enough, the citizens, businesses, industries and other government entities pooled their resources to make it happen.

And thus, our tale comes to its happy beginning eight years ago with the opening of the Center for Education and Performing Arts (CEPA).

Since then, CEPA has been the site of community theater productions, recitals, conferences, symposiums, private events, a host of school functions, concerts and performances by nationally known artists, basketball games, high school wrestling matches, archery tournaments, JROTC competitions, graduations, church services, and – right now – a Smithsonian exhibit with local flavor.

“CEPA has brought a whole new dimension to Pell City,” said Kathy McCoy, who was executive director for seven years and is the current artistic director. “We are the gathering place for Pell City.”

Also called Pell City Center, CEPA features a 399-seat theater-concert hall and a 2,100-seat sports arena.

Plus, it boasts the only movie theater in the area, McCoy said.

CEPA, however, does not sit silently, waiting for a concert here and a theatrical performance there. Rather, activity at the building is nearly constant.

During the school year, for example, the theater is used daily for drama classes, said Kelly Wilkerson, CEPA’s executive director.

Much of the time, especially during December, the center is in use every day of the week, Wilkerson said. Sometimes, two events are happening simultaneously.

“It definitely gets a lot of use,” he said.

That is part of the beauty of a performing arts center, said Barbara Reed, public information officer of Alabama State Council on the Arts in Montgomery.

“Community arts centers provide access to a wide range of art and performance opportunities, which bring many people together,” Reed said. “These centers are often the heartbeat of smaller cities. Its programming inspires children, adults and families alike, creating a vibrant and connected community.”

Reed said any community is blessed to have a performing arts center.

“It put us on the cultural map of Alabama,” said Bill Hereford, who was mayor from 2008 to 2012.

Dr. Michael Barber, superintendent of Pell City Schools, said the center has had a significant impact on the school system.

“It has transformed our school system in several ways,” Barber said.

Having the center has helped to revive the high school drama department; provided a venue to bring shows to the students instead of having to transport them elsewhere to see productions; has given students stage performance opportunities; has accommodated the entire high school student body for assemblies, and has offered space for teacher training during in-service meetings, Barber said.

The school system, he continued, even got to host a State Board of Education meeting at CEPA, “which was a great honor.”

Besides benefiting the students and residents, programs and functions at the center stand to boost the local economy, said McCoy.

Besides benefiting the students and residents, programs and functions at the center stand to boost the local economy, said McCoy.

A significant percentage of audience members come from outside Pell City, she said. While in Pell City, those patrons dine, refuel and maybe even stay in a hotel.

The chance to seek out and promote local talent is yet another advantage of the center, McCoy said. A group of 30 or so actors and actresses have been brought together to form the community theater group, Pell City Players.

“I can’t say enough about Pell City Players. We have some really good actors here. I’ve kind of been amazed,” McCoy said of the award-winning group. McCoy came to CEPA from Monroeville, where she led the Mockingbird Players, who performed both nationally and internationally.

In 2007, Pell City Players presented their first production, which was Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Since then, they have done two or three productions a year – some comedy, some drama, some musicals. Among the group’s list of presentations in the past seven years are Dearly Departed, To Kill a Mockingbird, Crimes of the Heart and It’s a Wonderful Life.

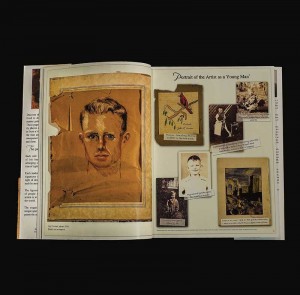

At the opening of the Smithsonian exhibit, The Way We Worked, the players used performing arts to augment visual arts. The thespians dressed as figures in Pell City’s history to tell their stories, said McCoy.

Having a community theater has naturally led to summer drama camps for children, preening them to take a future place in Pell City Players, said McCoy.

Ginger McCurry of Pell City is the instructor. During the camps, students learn the crafts of acting and staging a production. A show at the end of the two weeks allows them to demonstrate what they have learned.

This summer, their production was Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, said Wilkerson.

McCurry has staged shows at the center since it opened. She presented students in concerts when she was music teacher at Coosa Valley Elementary and choir teacher at Duran Junior High North and Duran Junior High South and has staged productions as theater teacher at Pell City High School.

“I’m very pleased with this theater,” she said. “It was designed for everyone to be able to hear and to see. The setup is excellent, in my opinion.”

Wilkerson said the “flying system” of stage rigging lets scenes be lowered into place or lifted out of sight when not needed. He noted there is also an orchestra pit for live accompaniment.

When the orchestra pit is not in use, a safety covering makes it part of the stage, Hereford added.

McCurry is just as complimentary of the potential of the area’s residents.

“Pell City is covered up with talent,” McCurry continued. There is more of it represented in the schools and in the community “than I can imagine.”

She would like to see the formation of a civic chorale to showcase some of those abilities.

This summer, the center also worked to groom another kind of artist – those gifted in visual arts. The center hosted an art camp for the first time.

Act I, Scene I

The center’s beginning dates back more than 14 years.

Former Mayor Guin Robinson said that after he moved to Pell City in 1989, he heard time and again about the need for an arts center. After he was elected mayor some 10 years later, the city government conducted a needs assessment and found the desire for such a facility.

In May 2000, the mayor and Council appointed an “auditorium feasibility committee.” The group consisted of Elizabeth Parsons, Ronnie White, Harold Williams, Jason Goodgame, Terry Wilson, Brenda Fields, Gaston Williamson, Suellen Brown, Carol Pappas and Bob Barnett, who would serve as chairman.

Along the way, Dr. Bobby Hathcock, then-superintendent of Pell City Schools, expressed the need for a new gymnasium for Pell City High School, Robinson said.

By March 2003, the City Council and school system were considering combining efforts to build an auditorium and gymnasium, Council records show.

In November of that year, Robinson’s state-of-the-city address referenced the venture as being a $4.5 million project, with the city’s portion coming from a multipurpose bond issue. The State of Alabama and the St. Clair County Commission also provided some funding. Yet, still more was needed.

Robinson asked Hereford, who was presiding circuit judge at the time, to head a committee to raise funds from local individuals, businesses and industry.

Hereford said approximately $350,000 was given through that fundraising campaign.

“That’s a lot of money to come in from a community our size,” Hereford said. “(The center) wasn’t that hard to sell. People were ready for it. If you’ve got a good project and a real need, the people of this city will step up.”

Groundbreaking for the center occurred in 2004 before Robinson’s administration ended. The center opened in 2006.

By 2008 when Hereford became mayor, the center was taking on a larger and larger role in the life of the community, and Pell City Players had come into existence. The community theater and the high school drama department were “doing absolutely amazing things,” Hereford said.

During Hereford’s tenure as mayor, a governing board for the center was created. Charter members were Ed Gardner, the late Carole Barnett, Don Perry, Carol Pappas and Judge Charles Robinson, president. Matthew Pope and Henry Fisher replaced Perry and Robinson on the board, and Pappas is president. New members are expected to replace Gardner and Barnett in the next few weeks.

Managing the facility and programming events is now done by CEPA Management Corp., which operates independently of the city and school system, McCoy and Wilkerson said. It is a 501(c)3 entity.

Recently, the center added a movie screen and projector system, giving the community another outlet for entertainment. The theater-concert hall easily transforms into a movie theater as the movie screen is lowered into place by the “flying” stage rigging.

The movie theater comes courtesy of allocations in the amount of $6,200 from the city for the projector and electronics upgrades at the building; $7,500 from the Arthur Smith Estate for the movie screen and sound reinforcement upgrades and $1,000 from Congressman Mike Rogers for a new popcorn popper and concession supplies, Wilkerson said.

Already, the center has presented the movies Frozen and Steel Magnolias.

Wilkerson noted that special showings are possible for people with particular needs, such as sensory challenges. Private screenings are available, too.

The goal for the movies is the same as it is with the other presentations at the center – to provide quality entertainment at an affordable price, said McCoy and Wilkerson.

The center continues to receive funds through “Support the Arts” specialty vehicle tags; from businesses, industry and state arts council grants to bring certain groups or performances to Pell City, to decrease the price of student tickets for school-related productions or to provide tickets for students who cannot afford to pay, said Wilkerson.

Robinson said the story of Pell City Center is that “some things just come together at the right time. I think that project was worth waiting on.”

A lot of work and dedication from all involved and much support from the citizens went into this project, said Robinson, who now lives in Birmingham.

“It was definitely a labor of love,” he said.

Additional assistance with this story was provided by Penny Isbell

and Anna Hardy of the City of Pell City.